Swami Vivekananda (January 12, 1863 – July 4, 1902) was an Indian saint, social reformer, and a great teacher of mankind. He was the foremost disciple of Bhagavan Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, often considered as the prophet of the modern age. Swami Vivekananda was a towering spiritual personality, a great thinker and orator, and the prophet of universal harmony and progress.

Sri Ramakrishna re-educated Narendranath (young Vivekananda) in the essentials of Hinduism. The beliefs Narendra had learnt on his mother’s lap had been shattered by college education, but the young man now came to know that Hinduism does not consist of dogmas or creeds; it is an inner experience, deep and inclusive, which respects all faiths, all thoughts, all efforts and all realisations. Unity in diversity is its ideal.

Narendra further learnt that religion is a vision which, in the end, transcends all barriers of caste and race and breaks down the limitations of time and space. He learnt from the Master that the Personal God and worship through symbols ultimately lead the devotee to the realisation of complete oneness with Supreme Consciousness. The Master taught him the divinity of the soul, the non-duality of the Godhead, the unity of existence, and the harmony of religions. He showed Naren by example how a man could reach perfection in this very life. The disciple learned that the Master had realised the same God-consciousness by following the diverse disciplines of Hinduism, Christianity, and Islam.

Regarding foreign countries, Vivekananda was the first authoritative exponent to Western nations of the ideas of the Vedas and Upanishads. He had no dogma of his own to set forth. ‘I have never,’ he said, ‘quoted anything but the Vedas and Upanishads, and from them only comes the word strength!’ He preached mukti (liberation, freedom from reincarnation) instead of heaven, enlightenment instead of salvation, the realisation of the Immanent Unity, Brahman, instead of God, and the truth of all faiths, instead of the binding force of any one.

The Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893 offered Swami Vivekananda the long-desired opportunity to present the eternal and universal truths of his Aryan ancestors before the Western world. And he rose to the occasion. As he stood on the platform to give his message, he formed, as it were, the confluence of two great streams of thought, the two ideals that had moulded human culture. The vast audience before him represented exclusively the Occidental mind – young, alert, restless, inquisitive, tremendously honest, well-disciplined, and at ease with the physical universe – but skeptical about the profundities of the supersensuous world and unwilling to accept spiritual truths without rational proof. And behind him lay the ancient world of India, with its diverse religious and philosophical discoveries, with its saints and prophets who investigated Reality through self-control and contemplation, unruffled by the passing events of the transitory life and absorbed in contemplation of the Eternal Verities. Vivekananda’s education, upbringing, personal experiences, and contact with the God-man of modern India had pre-eminently fitted him to represent both ideals and to remove their apparent conflict.

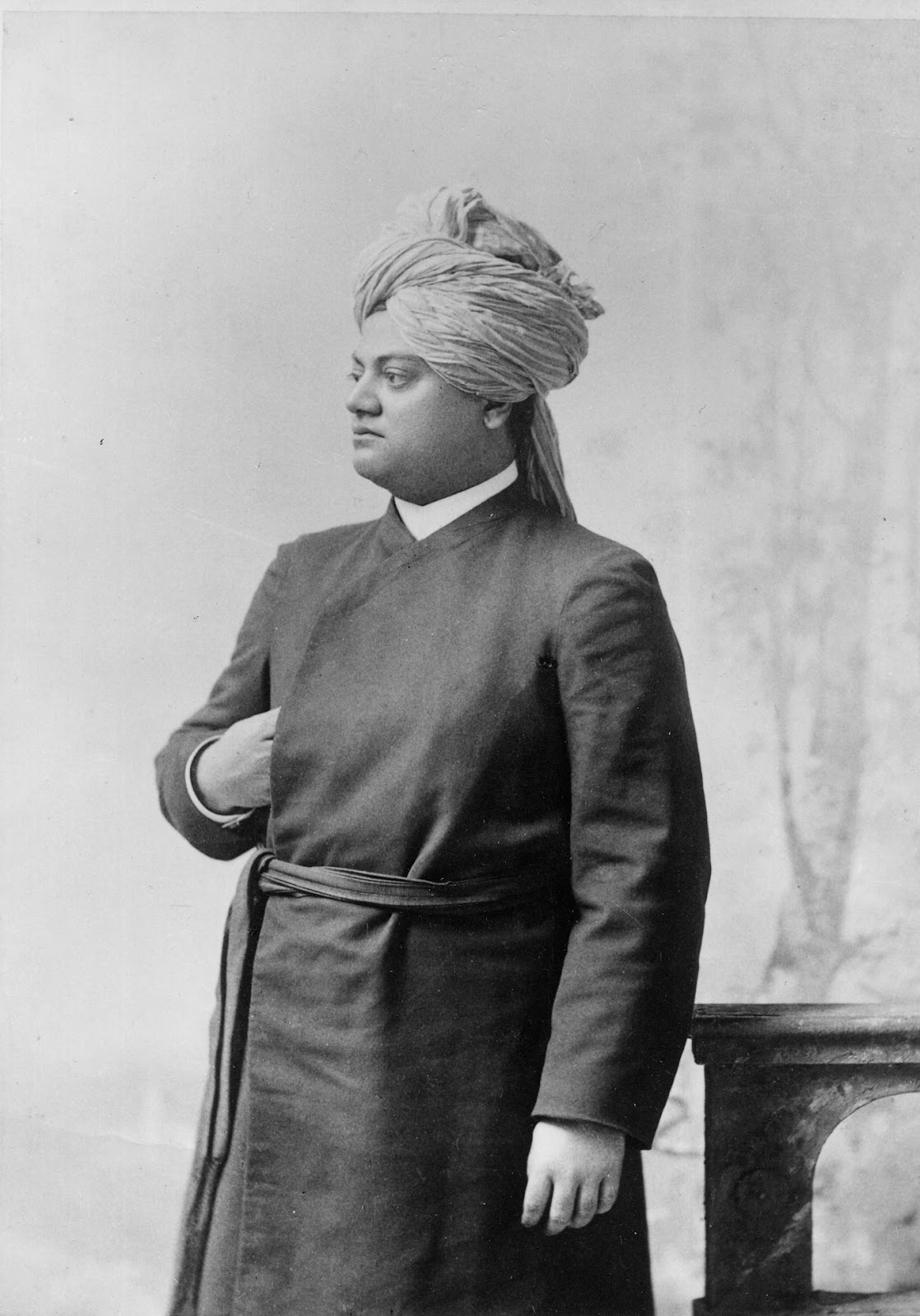

Swami Vivekananda’s inspiring personality was well-known both in India and in America during the last decade of the nineteenth century and the first decade of the twentieth. The unknown monk of India suddenly leapt into fame at the Parliament of Religions held in Chicago in 1893, at which he represented Hinduism. His vast knowledge of Eastern and Western culture, his deep spiritual insight, fervid eloquence, and brilliant conversation drew many people to him. In addition, his broad human sympathy, colourful personality, and handsome figure made an irresistible appeal to the many types of Americans who came in contact with him. People who saw or heard Vivekananda even once still cherish his memory after a lapse of more than half a century.

In America, Vivekananda’s mission was to interpret India’s spiritual culture, especially in its Vedantic setting. He also tried to enrich the religious consciousness of the Americans through the rational and humanistic teachings of the Vedanta philosophy. He became India’s spiritual ambassador and pleaded eloquently for a better understanding between India and the New World to create a healthy synthesis of East and West, religion and science.

In his motherland, Vivekananda is regarded as the patriot saint of modern India and an inspirer of her dormant national consciousness. To the Hindus, he preached the ideal of a strength-giving and man-making religion. Service to man as the visible manifestation of the Godhead was the particular form of worship he advocated for the Indians, devoted as they were to the rituals and myths of their ancient faith. Many political leaders of India have publicly acknowledged their indebtedness to Swami Vivekananda.

Swami’s mission was both national and international. A lover of humankind, he strove to promote peace and brotherhood on the spiritual foundation of the Vedantic Oneness of existence. A mystic of the highest order, Vivekananda had a direct and intuitive experience of Reality. He derived his ideas from that unfailing source of wisdom and often presented them in the soul-stirring language of poetry.

The natural tendency of Vivekananda’s mind, like that of his Master, Ramakrishna, was to soar above the world and forget itself in contemplation of the Absolute. But another part of his personality bled at the sight of human suffering in East and West. It might appear that his mind seldom found a point of rest in its oscillation between the contemplation of God and service to man. Be that as it may, he chose, in obedience to a higher call, service to man as his mission on earth, and this choice has endeared him to many people in the West, Americans in particular.

In the course of a short life of thirty-nine years (1863-1902), of which only ten were devoted to public activities – and those, too, in the midst of acute physical suffering – he left for posterity his four classics: Jnana-Yoga, Bhakti-Yoga, Karma-Yoga, and Raja-Yoga, all of which are outstanding treatises on Hindu philosophy. In addition, he delivered innumerable lectures, wrote inspired letters in his own hand to his many friends and disciples, composed numerous poems, and acted as a spiritual guide to the many seekers who came to him for instruction. He also organised the Ramakrishna Order of monks, the most outstanding religious organisation in modern India. It is devoted to propagating the Hindu spiritual culture not only in Swami’s native land but also in America and other parts of the world.

Swami Vivekananda once spoke of himself as a ‘condensed India’. His life and teachings are of inestimable value to the West for an understanding of the mind of Asia. William James, the Harvard philosopher, called him the ‘paragon of Vedantists’. Max Muller and Paul Deussen, the famous Orientalists of the nineteenth century, held him in genuine respect and affection. ‘His words,’ writes Romain Rolland, ‘are great music, phrases in the style of Beethoven, stirring rhythms like the march of Handel choruses. I cannot touch these sayings of his, scattered as they are through the pages of books, at thirty years’ distance, without receiving a thrill through my body like an electric shock. And what shocks, what transports, must have been produced when in burning words they issued from the lips of the hero!’

Born Narendranath Dutta, into an affluent Bengali family in Calcutta, Vivekananda was one of the eight children of Vishwanath Dutta and Bhuvaneshwari Devi. He was born on January 12, 1863, on the occasion of Makar Sankranti. Father Vishwanath was a successful attorney with considerable influence in society. Narendranath’s mother Bhuvaneshwari was a woman endowed with a strong, God-fearing mind who had a great impact on her son.

As a young boy, Narendranath displayed a sharp intellect. His mischievous nature belied his interest in music, both instrumental as well as vocal. He also excelled in his studies, first at the Metropolitan institution and later at the Presidency College in Calcutta. By the time he graduated from college, he had acquired a vast knowledge of different subjects. He was active in sports, gymnastics, wrestling and bodybuilding. He was an avid reader, reading almost everything under the sun. He pursued the Hindu scriptures like the Bhagavad Gita and the Upanishads. On the other hand, he studied Western philosophy, history and spirituality by David Hume, Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Herbert Spencer.

Spiritual Crisis and Relationship with Ramkrishna Paramhansa

Although Narendranath’s mother was a devout woman and he had grown up in a religious atmosphere at home, he underwent a deep spiritual crisis at the start of his youth. His well-studied knowledge led him to question the existence of God, and for some time, he believed in Agnosticism. Yet he could not completely ignore the existence of a Supreme Being. He became associated with the Brahmo Movement led by Keshab Chandra Sen. The Bramho Samaj recognised one God, unlike the idol-worshipping, superstition-ridden Hinduism. However, the host of philosophical questions regarding the existence of God roiling through his mind remained unanswered. During this spiritual crisis, Vivekananda first heard about Sri Ramakrishna from William Hastie, the Principal of the Scottish Church College.

Earlier, to satisfy his intellectual quest for God, Narendranath had visited prominent spiritual leaders from various religions, asking them a single question, ‘Have you seen God?’ Each time he came away without a satisfying answer. He put the same question to Sri Ramakrishna at his residence in Dakshineswar Kali Temple compounds. Without a moment’s hesitation, Sri Ramakrishna replied: ‘Yes, I have. I see God as clearly as I see you, only in a much deeper sense.’ Vivekananda, initially unimpressed by the simplicity of Ramakrishna, was astonished by his reply. Ramakrishna gradually won over the argumentative young man with his patience and love. The more Narendranath visited Dakshineshwar, the more his questions were answered.

Spiritual Awakening

In 1884, Narendranath underwent considerable financial distress due to his father’s death, as he had to support his mother and younger siblings. He asked Ramakrishna to pray to the Goddess for the financial welfare of his family. On Ramakrishna’s suggestion, he himself went to the temple to pray. But once he faced the Goddess, he could not ask for money and wealth; instead, he asked for ‘Vivek’ (conscience) and ‘Bairagya’ (reclusion). That day marked the complete spiritual awakening of Narendranath, and he found himself drawn to an ascetic way of life.

Life of a Monk

In the middle of 1885, Ramakrishna, who had been suffering from throat cancer, fell seriously ill. In September 1885, Sri Ramakrishna was moved to Shyampukur in Calcutta, and a few months later Narendranath took a rented villa at Cossipore. Here, he formed a group of young people who were ardent followers of Sri Ramakrishna, and together they nursed their Guru with loving care. Finally, on August 16, 1886, Sri Ramakrishna gave up his mortal body.

After the death of Sri Ramakrishna, around fifteen of his disciples, including Narendranath, began to live together in a dilapidated building at Baranagar in North Calcutta, which was named Ramakrishna Math, the monastic order of Ramakrishna. Here, in 1887, they formally renounced all ties to the world and took vows of monkhood. The brotherhood rechristened itself, and Narendranath emerged as Vivekananda, meaning ‘the bliss of discerning wisdom’.

The brotherhood subsisted on alms donated voluntarily by patrons during holy begging or ‘madhukari’, and performed yoga and meditation. Vivekananda left the Math in 1888 and went on a tour of India on foot as a ‘Parivrajak’ (wandering monk). He travelled the breadth of the country, absorbing much of the social, cultural and religious aspects of the people he met. He witnessed life’s adversities and the many ailments that ordinary people faced and vowed to dedicate his life to bring relief to the suffering.

Lecture at the World Parliament of Religions

Vivekananda learned about the World Parliament of Religions to be held in Chicago, America, 1893. He wanted to represent India, Hinduism and Guru Sri Ramakrishna’s philosophies. His disciples raised money in Madras, and Ajit Singh, Raja of Khetri, and Vivekananda left for Chicago on May 31, 1893, from Bombay.

He faced many hardships on his way to Chicago, but his spirit remained as indomitable as ever. On 11 September 1893, when the time came, he took the stage and stunned everyone with his opening line, ‘My brothers and sisters of America.’ He received a standing ovation from the audience for the opening phrase. He went on to describe the principles of Vedanta and their spiritual significance, putting Hinduism on the map of World Religions.

He spent the next two-and-a-half years in America and founded the Vedanta Society of New York in 1894. He also travelled to the United Kingdom to preach the tenets of the Vedanta and Hindu Spiritualism to the Western world.

Teachings and Ramakrishna Mission

Vivekananda returned to India in 1897 amidst a warm reception from the common and royal alike. He reached Calcutta after a series of lectures across the country and founded the Ramakrishna Mission on May 1, 1897, at Belur Math near Calcutta. The goals of the Ramakrishna Mission were based on the ideals of Karma Yoga, and its primary objective was to serve the poor and distressed population of the country. The Ramakrishna Mission undertook various forms of social service like establishing and running schools, colleges and hospitals, propagation of practical tenets of Vedanta through conferences, seminars and workshops, and initiating relief and rehabilitation work across the country.

Death

Swami Vivekananda had predicted that he would not live till the age of forty. On July 4, 1902, he went about his days’ work at the Belur Math, teaching Sanskrit grammar to the pupils. He retired to his room in the evening and died during meditation at around 9 pm, at the age of 39. He is said to have attained ‘Mahasamadhi,’ leaving the body consciously and at will. The great saint was cremated on the Banks of the river Ganga in Belur, opposite where Ramakrishna was cremated sixteen years earlier.

The meeting of Narendra and Sri Ramakrishna was an essential event in the lives of both. A storm had been raging in Narendra’s soul when he came to Sri Ramakrishna, who himself had passed through a similar struggle but was now firmly anchored in peace due to his intimate communion with the Godhead and his realisation of Brahman as the immutable essence of all things.

A genuine product of the Indian soil and thoroughly acquainted with the spiritual traditions of India, Sri Ramakrishna was ignorant of the modern way of thinking. But Narendra was the symbol of the modern spirit. Inquisitive, alert, and intellectually honest, he possessed an open mind and demanded rational proof before accepting any conclusion as valid. As a loyal member of the Brahmo Samaj, he was critical of image worship and the rituals of the Hindu religion. He did not feel the need for a Guru, a human intermediary between God and man. He was even skeptical about the existence of such a person, who was said to be free from human limitations and to whom an aspirant was expected to surrender himself completely and offer worship as to God. Ramakrishna’s visions of gods and goddesses he openly ridiculed and called them hallucinations.

On his third visit, Sri Ramakrishna took him to a neighbouring garden and, in a state of trance, touched him. Completely overwhelmed, Naren lost consciousness.

Sri Ramakrishna, referring later to this incident, said that after putting Naren into a state of unconsciousness, he had asked him many questions about his past, his mission in the world, and the duration of his present life. The answer had only confirmed what he himself had thought about these matters. Ramakrishna told his other disciples that Naren had attained perfection even before this birth, that he was an adept in meditation, and that the day Naren recognised his true self, he would give up the body by an act of will through yoga. Often he was heard saying that Naren was one of the Saptarishis, or Seven Sages, who live in the realm of the Absolute. He narrated to them a vision he had received regarding the disciple’s spiritual heritage.

Absorbed, one day, in samadhi, Ramakrishna had found that his mind was soaring high, going beyond the physical universe of the sun, moon, and stars and passing into the subtle region of ideas. As it continued to ascend, the forms of gods and goddesses were left behind, and it crossed the luminous barrier separating the phenomenal universe from the Absolute, finally entering the transcendental realm. There, Ramakrishna saw seven venerable sages absorbed in meditation. These, he thought, must have surpassed even the gods and goddesses in wisdom and holiness, and as he was admiring their unique spirituality, he saw a portion of the undifferentiated Absolute become congealed, as it were, and take the form of a Divine Child. Gently clasping the neck of one of the sages with His soft arms, the Child whispered something in his ear, and at this magic touch, the sage awoke from meditation. He fixed his half-open eyes upon the wondrous Child, who said in great joy: ‘I am going down to earth. Won’t you come with me?’ With a benign look, the sage expressed assent and returned to deep spiritual ecstasy. Ramakrishna was amazed to observe that a tiny portion of the sage, however, descended to earth, taking the form of light, which struck the house in Calcutta where Narendra’s family lived, and when he saw Narendra for the first time, he at once recognised him as the incarnation of the sage. He also admitted that the Divine Child who brought about the descent of the rishi was none other than himself.

For five years, Narendra closely watched the Master, never allowing himself to be influenced by blind faith, always testing the words and actions of Sri Ramakrishna in the crucible of reason. It cost him many sorrows and much anguish before he accepted Sri Ramakrishna as his Guru and the ideal of the spiritual life. But when the acceptance came, it was wholehearted, final, and irrevocable. The Master, too, was overjoyed to find a disciple who doubted, and he knew that Naren was the one to carry his message to the world.

Sri Ramakrishna, the perfect teacher that he was, never laid down identical disciplines for disciples of diverse temperaments. He did not insist that Narendra should follow strict rules about food, nor did he ask him to believe in the reality of the gods and goddesses of Hindu mythology. It was not necessary for Narendra’s philosophic mind to pursue the disciplines of idol worship. But a strict eye was kept on Naren’s practice of discrimination, detachment, self-control, and regular meditation. Sri Ramakrishna enjoyed Naren’s vehement arguments with the other devotees regarding the dogmas and creeds of religion and was delighted to hear him tear to shreds their unquestioning beliefs. But when, as often happened, Naren teased the gentle Rakhal for showing reverence to the Divine Mother Kali, the Master would not tolerate these attempts to unsettle the brother disciple’s faith in the forms of God.

On one occasion, Sri Ramakrishna proposed to transfer to Narendranath many of the spiritual powers that he had acquired as a result of his ascetic disciplines and visions of God. Naren did not doubt the Master possessing such powers and asked if they would help him to realise God. Sri Ramakrishna replied in the negative but added that they might assist him in his future work as a spiritual teacher. ‘Let me realise God first,’ said Naren, ‘and then I shall perhaps know whether or not I want supernatural powers. If I accept them now, I may forget God, use them selfishly, and thus come to grief.’ Sri Ramakrishna was highly pleased to see his chief disciple’s single-minded devotion.

In his heart of hearts, Naren was a lover of God. Pointing to his eyes, Ramakrishna said that only a bhakta possessed such a tender look; the eyes of the jnani were generally dry. In his later years, Narendra said many times, comparing his own spiritual attitude with that of the Master: ‘He was a jnani within, but a bhakta without, but I am a bhakta within, and a jnani without.’ He meant that Ramakrishna’s gigantic intellect was hidden under a thin layer of devotion, and Narendra’s devotional nature was covered by a cloak of knowledge.

Sri Ramakrishna re-educated Narendranath in the essentials of Hinduism. Ramakrishna, the fulfilment of the three hundred million Hindus’ spiritual aspirations for the past three thousand years, was the embodiment of the Hindu faith. A college education had shattered the beliefs Narendra had learnt on his mother’s lap, but the young man now came to know that Hinduism does not consist of dogmas or creeds; it is an inner experience, deep and inclusive, which respects all faiths, all thoughts, all efforts and all realisations. Unity in diversity is its ideal.

Narendra further learnt that religion is a vision that ultimately transcends all barriers of caste and race and breaks down the limitations of time and space. He learnt from the Master that the Personal God and worship through symbols also can lead the devotee to the realisation of complete oneness with the Deity. The Master taught him the divinity of the soul, the non-duality of the Godhead, the unity of existence, and the harmony of religions. He showed Naren by his example how a man in this very life could reach perfection. The disciple found that the Master had realised the same God-consciousness by following the diverse disciplines of Hinduism, Christianity, and Islam.

A passion for God was literally consuming Naren. The world appeared to him to be utterly distasteful. When the Master reminded him of his college studies, the disciple said, ‘I would feel relieved if I could swallow a drug and forget all I have learnt.’ He spent night after night in meditation under the trees in the Panchavati at Dakshineswar, where Sri Ramakrishna, during the days of his spiritual discipline, had contemplated God. He felt the awakening of the Kundalini (The spiritual energy, usually dormant in man but aroused by the practice of spiritual disciplines) and had other spiritual visions.

One day at Cossipore, Narendra was meditating under a tree with Girish, another disciple. The place was infested with mosquitoes. Girish tried in vain to concentrate his mind. Casting his eyes on Naren, he saw him absorbed in meditation, though his body appeared to be covered by a blanket of insects.

A few days later, Narendra’s longing seemed to have reached the breaking point. He spent an entire night walking around the garden house at Cossipore, repeating Rama’s name in a heart-rending manner. In the early hours of the morning, Sri Ramakrishna heard his voice, called him to his side, and said affectionately: ‘Listen, my child, why are you acting that way? What will you achieve by such impatience?’ He stopped for a minute and then continued: ‘See, Naren. What you have been doing now, I did for twelve long years. A storm raged in my head during that period. What will you realise in one night?’

But the Master was pleased with Naren’s spiritual struggle and made no secret of his wish to make him his spiritual heir. He wanted Naren to look after the young disciples. ‘I leave them in your care,’ he said to him. ‘Love them intensely and see that they practise spiritual disciplines even after my death and that they do not return home.’ He asked the young disciples to regard Naren as their leader. It was an easy task for them. Then, one day, Sri Ramakrishna initiated several of the young disciples into monastic life and thus laid the foundation of the future Ramakrishna Order of Monks.

The disciples sadly watched the gradual wasting away of Sri Ramakrishna’s physical frame. His body became a mere skeleton covered with skin; the suffering was intense. But he devoted his remaining energies to the training of the disciples, especially Narendra. He had been relieved of his worries about Narendra, for the disciple now admitted the divinity of Kali, whose will controls all things in the universe. Naren said later on: ‘From the time he gave me over to the Divine Mother, he retained the vigour of his body only for six months. The rest of the time — and that was two long years — he suffered.’

One day the Master, unable to speak even in a whisper, wrote on a piece of paper: ‘Narendra will teach others.’ The disciple hesitated. Sri Ramakrishna replied: ‘But you must. Your very bones will do it.’ He further said that all his supernatural powers would work through his beloved disciple.

A short while before the curtain finally fell on Sri Ramakrishna’s earthly life, the Master called Naren to his bedside one day. Gazing intently upon him, he passed into deep meditation. Naren felt that a subtle force resembling an electric current was entering his body. He gradually lost outer consciousness. After some time, he regained knowledge of the physical world and found the Master weeping. Sri Ramakrishna said to him: ‘O Naren, today I have given you everything I possess — now I am no more than a fakir, a penniless beggar. By the powers I have transmitted to you, you will accomplish great things in the world, and not until then will you return to the source whence you have come.’

From that day on, Narendra became the channel of Sri Ramakrishna’s powers and the spokesman for his message.

Naren’s keen mind understood the subtle implications of Sri Ramakrishna’s teachings. One day the Master said that the three salient disciplines of Vaishnavism were the love of God’s name, service to the devotees, and compassion for all living beings. But he did not like the word compassion and said to the devotees: ‘How foolish to speak of compassion! Man is an insignificant worm crawling on the earth — and he to show compassion to others! This is absurd. It must not be compassion but service to all. Recognise them as God’s manifestations and serve them.’

‘The Christian is not to become a Hindu or a Buddhist, nor is a Hindu or a Buddhist to become a Christian. But each must assimilate the spirit of the others and yet preserve his individuality and grow according to his law of growth. If the Parliament of Religions has shown anything to the world, it is this: It has proved to the world that holiness, purity, and charity are not the exclusive possessions of any church and that every system has produced men and women of the holiest character. In the face of this evidence, if anybody dreams of the exclusive survival of his religion and the destruction of the others, I pity him from the bottom of my heart and point out to him that upon the banner of every religion will soon be written, despite resistance: ‘Help and not Fight,’ ‘Assimilation and not Destruction,’ ‘Harmony and Peace and not Dissension.’

While synthesising and popularising various strands of Hindu thought, most notably classical Yoga and (Advaita) Vedanta, Vivekananda was also influenced by Western ideas such as Universalism via Unitarian missionaries who collaborated with the Brahmo Samaj. His initial beliefs were shaped by Brahmo concepts, which included belief in a formless God and the deprecation of idolatry, and a ‘streamlined, rationalised, monotheistic theology strongly coloured by a selective and modernistic reading of the Upanisads and the Vedanta.’ He propagated the idea that ‘the divine, the absolute, exists within all human beings regardless of social status’ and that ‘seeing the divine as the essence of others will promote love and social harmony.’ Via his affiliations with Keshub Chandra Sen’s Nava Vidhan, the Freemasonry lodge, the Sadharan Brahmo Samaj, and Sen’s Band of Hope, Vivekananda became acquainted with Western esotericism.

He was also influenced by Ramakrishna, who gradually brought Narendra to a Vedanta-based worldview that provides the ontological basis for ‘sivajnane jiver seva’, the spiritual practice of serving human beings as actual manifestations of God.

Vivekananda maintained that the essence of Hinduism was best expressed in Adi Shankara’s Advaita Vedanta philosophy. Nevertheless, following Ramakrishna, and in contrast to Advaita Vedanta, Vivekananda believed that the Absolute is both immanent and transcendent. According to Anil Sooklal, Vivekananda’s neo-Vedanta “reconciles Dvaita or dualism and Advaita or non-dualism,” viewing Brahman as ‘one without a second’, ‘yet both qualified, saguna, and without quality, nirguna.’ Vivekananda summarised Vedanta as follows, giving it a modern and Universalistic interpretation, showing the influence of classical yoga:

‘Each soul is potentially divine. The goal is to manifest this Divinity by controlling nature, external and internal. Do this either by work, or worship, or mental discipline, or philosophy—by one, more, or all of these—and be free. This is the whole of religion. Doctrines, dogmas, rituals, books, temples, or forms are but secondary details.’

In the course of a short life of thirty-nine years (1863-1902), of which only ten were devoted to public activities – and those, too, amid acute physical suffering – he left for posterity his four classics: Jnana-Yoga, Bhakti-Yoga, Karma-Yoga, and Raja-Yoga, all of which are outstanding treatises on Hindu philosophy. In addition, he delivered innumerable lectures, wrote inspired letters in his own hand to his many friends and disciples, composed numerous poems, and acted as a spiritual guide to the many seekers who came to him for instruction. He also organised the Ramakrishna Order of Monks, one of modern India’s most outstanding religious organisations. It is devoted to promoting the Hindu spiritual culture not only in the Swami’s native land but also in America and other parts of the world.

Karma Yoga

The goals of the Ramakrishna Mission are based on the ideals of Karma Yoga, and its primary objective was to serve the poor and distressed population of the country. The Ramakrishna Mission undertook various forms of social service like establishing and running schools, colleges and hospitals, propagation of practical tenets of Vedanta through conferences, seminars and workshops, and initiating relief and rehabilitation work across the country.

THE IDEAL OF KARMA-YOGA

‘The grandest idea in the religion of the Vedanta is that we may reach the same goal by different paths; these paths I have generalised into four, viz. those of work, love, psychology, and knowledge. But you must, at the same time, remember that these divisions are not very marked and quite exclusive of each other. Each blend into the other. But according to the type which prevails, we name the divisions. It is not that you can find men who have no other faculty than that of work, nor that you can find men who are no more than devoted worshippers only, nor that there are men who have no more than mere knowledge. These divisions are made in accordance with the type or the tendency that may be seen to prevail in a man. We have found that, in the end, all these four paths converge and become one. All religions and all methods of work and worship lead us to one and the same goal.

‘I have already tried to point out that goal. It is freedom as I understand it. Everything we perceive around us is struggling towards freedom, from the atom to the man, from the insentient, lifeless particle of matter to the highest existence on earth, the human soul. The whole universe is, in fact, the result of this struggle for freedom. In all combinations, every particle is trying to go its own way, to fly from the other particles; but the others are holding it in check. Our earth is trying to fly away from the sun and the moon from the earth. Everything tends towards infinite dispersion. All that we see in the universe has for its basis this one struggle towards freedom; it is under the impulse of this tendency that the saint prays and the robber robs. When the line of action taken is not a proper one, we call it evil; and when the manifestation of it is proper and high, we call it good. But the impulse is the same, the struggle towards freedom. The saint is oppressed by the knowledge of his condition of bondage, and he wants to get rid of it, so he worships God. The thief is oppressed by the idea that he does not possess certain things, and he tries to get rid of that want, to obtain freedom from it, so he steals. Freedom is the one goal of all nature, sentient or insentient; consciously or unconsciously, everything is struggling towards that goal. The freedom the saint seeks is very different from that the robber seeks; the freedom loved by the saint leads him to the enjoyment of infinite, unspeakable bliss, while that which the robber has set his heart on only forges other bonds for his soul.

‘There is to be found in every religion the manifestation of this struggle towards freedom. It is the groundwork of all morality, of unselfishness, which means getting rid of the idea that men are the same as their little body. When we see a man doing good work, and helping others, it means that he cannot be confined within the limited circle of ‘me and mine.’ There is no limit to this getting out of selfishness. All the great systems of ethics preach absolute unselfishness as the goal. Supposing a man’s absolute unselfishness can be reached, what becomes of him? He is no more the little Mr. So-and-so; he has acquired infinite expansion. The little personality he had before is now lost to him forever; he has become infinite, and the attainment of this infinite expansion is indeed the goal of all religions and all moral and philosophical teachings. The personalist, when he hears this idea philosophically put, gets frightened. At the same time, if he preaches morality, he, after all, teaches the very same idea himself. He sets no limit to the unselfishness of man. Suppose a man becomes perfectly unselfish under the personalistic system; how are we to distinguish him from the perfected ones in other systems? He has become one with the universe, and to become that is the goal of all; only the poor personalist has not the courage to follow his reasoning to its correct conclusion. Karma-Yoga is the attaining through unselfish work of that freedom which is the goal of all human nature. Every selfish action, therefore, retards our reaching the goal, and every unselfish action takes us towards the goal; that is why the only definition that can be given of morality is this: That which is selfish is immoral, and that which is unselfish is moral.

‘But, if you come to details, the matter will not be seen to be quite so simple. For instance, the environment often makes the details different, as I have already mentioned. The same action under one set of circumstances may be unselfish, and under another set, quite selfish. So we can give only a general definition and leave the details to be worked out by considering the differences in time, place, and circumstances. In one country, one kind of conduct is considered moral; in another, the same is immoral because the circumstances differ. The goal of all nature is freedom, and freedom is attained only by perfect unselfishness; every unselfish thought, word, or deed takes us toward the goal and, as such, is called moral. That definition, you will find, holds good in every religion and every system of ethics. In some systems of thought, morality is derived from a Superior Being — God. If you ask why a man ought to do this and not that, their answer is: ‘Because such is the command of God.’ But whatever the source from which it is derived, their code of ethics also has the same central idea — not to think of self but to give up self. And yet some persons, in spite of this high ethical idea, are frightened at the thought of having to give up their little personalities. We may ask the man who clings to the idea of little personalities to consider the case of a person who has become perfectly unselfish, who has no thought for himself, who does no deed for himself, who speaks no word for himself, and then say where his ‘himself’ is. That ‘himself’ is known to him only so long as he thinks, acts, or speaks for himself. If he is only conscious of others, of the universe, and of the all, where is his ‘himself’? It is gone forever.

‘Therefore, Karma-Yoga is a system of ethics and religion intended to attain freedom through unselfishness and good works. The Karma-Yogi need not believe in any doctrine whatever. He may not believe even in God, may not ask what his soul is, nor think of any metaphysical speculation. He has his own particular aim of realising selflessness, and he has to work it out himself. Every moment of his life must be realised because he has to solve by mere work, without the help of doctrine or theory, the same problem to which the Jnani applies his reason and inspiration, and the Bhakta his love.

‘We have now seen what work is. It is a part of nature’s foundation and always goes on. Those who believe in God understand this better because they know that God is not such an incapable being as will need our help. Although this universe will go on always, our goal is freedom, our goal is unselfishness, and according to Karma-Yoga, that goal is to be reached through work. All ideas of making the world perfectly happy may be good as motive powers for fanatics, but we must know that fanaticism brings forth as much evil as good. The Karma-Yogi asks why you require any motive to work other than the inborn love of freedom. Be beyond the common worldly motives. ;To work, you have the right, but not to the fruits thereof.’ Man can train himself to know and to practice that, says the Karma-Yogi. When the idea of doing good becomes a part of his very being, he will not seek any motive outside. Let us do good because it is good to do good; he who does good work even to get to heaven binds himself down, says the Karma-Yogi. Any work done, even with the least selfish motive, forges one more chain for our feet instead of making us free.

‘So the only way is to give up all the fruits of work, to be unattached to them. Know that this world is not we, nor are we this world; that we are not the body; that we in reality do not work. We are the Self, eternally at rest and at peace. Why should anything bind us? It is very good to say that we should be perfectly non-attached, but what is the way to do it? Instead of forging a new chain, every good work we do without ulterior motive will break one of the links in the existing chains. Every good thought that we send to the world without thinking of any return, will be stored up there and break one link in the chain, and make us purer and purer, until we become the purest of mortals. Yet, all this may seem rather quixotic and too philosophical, more theoretical than practical. I have read many arguments against the Bhagavad-Gita, and many have said that you cannot work without motives. They have never seen charitable work except under the influence of fanaticism, and, therefore, they speak in that way.

‘In conclusion, let me tell you in a few words about one man who carried this teaching of Karma-Yoga into practice. That man is Buddha. He is the one man who ever carried this into perfect practice. All the world prophets, except Buddha, had external motives to move them to unselfish action. The prophets of the world, with this single exception, may be divided into two sets, one set holding that they are incarnations of God come down on earth, and the other holding that they are only messengers from God; and both draw their impetus for work from outside, expect reward from outside, however highly spiritual may be the language they use. But Buddha is the only prophet who said, ‘I do not care to know your various theories about God. What is the use of discussing all the subtle doctrines about the soul? Do good and be good. And this will take you to freedom and to whatever truth there is.’ In the conduct of his life, he was absolutely without personal motives; and what man worked more than he? Show me in history one character who has soared so high above all. The whole human race has produced but one such character, such high philosophy, such wide sympathy. This great philosopher, preaching the highest philosophy, had the deepest sympathy for the lowest animals and never made any claims for himself. He is the ideal Karma-Yogi, acting entirely without motive, and the history of humanity shows him to have been the greatest man ever born; beyond compare the greatest combination of heart and brain that ever existed, the greatest soul-power that has ever been manifested. He is the first great reformer the world has seen. He was the first who dared to say, ‘Believe not because some old manuscripts are produced, believe not because it is your national belief, because you have been made to believe it from your childhood; but reason it all out, and after you have analysed it, then, if you find that it will do good to one and all, believe it, live up to it, and help others to live up to it.’ He works best without any motive, neither for money, nor for fame, nor anything else; when a man can do that, he will be a Buddha, and out of him will come the power to work in such a manner as will transform the world. This man represents the very highest ideal of Karma-Yoga.”

DEFINITION OF BHAKTI

‘Bhakti-Yoga is a real, genuine search after the Lord, a search beginning, continuing, and ending in love. One single moment of the madness of extreme love for God brings us eternal freedom. ‘Bhakti,’ says Narada in his explanation of the Bhakti-aphorisms, ‘is an intense love for God. When a man gets it, he loves all and hates none; he becomes satisfied forever. This love cannot be reduced to any earthly benefit because so long as worldly desires last, that kind of love does not come. Bhakti is greater than Karma, greater than Yoga because these are intended for an object in view, while Bhakti is its own fruition, its own means and its own end.’

‘Bhakti has been the one constant theme of our sages. Apart from the notable writers on Bhakti, such as Shandilya or Narada, the great commentators on the Vyasa-Sutras, evidently, advocates of knowledge (Jnana), have also something very suggestive to say about love. Even when the commentator is anxious to explain many, if not all, of the texts to make them import a sort of dry knowledge, the Sutras, in the chapter on worship especially, do not lend themselves to be easily manipulated in that fashion.

‘There is not that much difference between knowledge (Jnana) and love (Bhakti), as people sometimes imagine. As we go on, we shall see that they converge and meet at the same point. So also is it with Raja-Yoga, which, when pursued as a means to attain liberation, and not (as unfortunately it frequently becomes in the hands of charlatans and mystery-mongers) as an instrument to hoodwink the unwary, leads us also to the same goal.

‘The one great advantage of Bhakti is that it is the easiest and the most natural way to reach the great divine end in view; its great disadvantage is that in its lower forms, it often degenerates into hideous fanaticism. The fanatical crew in Hinduism, Islam, or Christianity have always been almost exclusively recruited from these worshippers on the lower planes of Bhakti. That singleness of attachment (Nishthâ) to a loved object, without which no genuine love can grow, is often the cause of the denunciation of everything else. All the weak and undeveloped minds in every religion or country have only one way of loving their own ideal, i.e. by hating every other ideal. Herein is the explanation of why the same man who is so lovingly attached to his ideal of God, so devoted to his ideal of religion, becomes a howling fanatic as soon as he sees or hears anything of any other ideal. This kind of love is somewhat like the canine instinct of guarding the master’s property against intrusion; only the dog’s instinct is better than the reason of man, for the dog never mistakes its master for an enemy in whatever dress he may come before it. Again, the fanatic loses all power of judgment. Personal considerations are, in his case, of such absorbing interest that it is no question at all what a man says — whether it is right or wrong, but the one thing he is always particularly careful to know is who says it. The same man who is kind, good, honest, and loving to people of his own opinion will not hesitate to do the vilest deeds when they are directed against persons beyond the pale of his own religious brotherhood.

‘But this danger exists only in that Bhakti stage, called the preparatory (Gauni). When Bhakti has become ripe and has passed into that form which is called the supreme (Para), no more is there any fear of these hideous manifestations of fanaticism; that soul which is overpowered by this higher form of Bhakti is too near the God of Love to become an instrument for the diffusion of hatred.

‘It is not given to all of us to be harmonious in building our characters in this life: yet we know that that character is of the noblest type in which all these three — knowledge and love and Yoga — are harmoniously fused. Three things are necessary for a bird to fly — the two wings and the tail as a rudder for steering. Jnana (Knowledge) is the one wing, Bhakti (Love) is the other, and Yoga is the tail that keeps up the balance. For those who cannot pursue all these three forms of worship together in harmony and take up, therefore, Bhakti alone as their way, it is necessary always to remember that forms and ceremonials, though absolutely necessary for the progressive soul, have no other value than taking us on to that state in which we feel the most intense love for God.

‘There is a little difference in opinion between the teachers of knowledge and those of love, though both admit the power of Bhakti. The Jnanis hold Bhakti to be an instrument of liberation; Bhaktas look upon it both as the instrument and the thing to be attained. To my mind, this is a distinction without much difference. Bhakti, when used as an instrument, really means a lower form of worship, and the higher form becomes inseparable from the lower form of realisation at a later stage. Each seems to lay great stress upon his own peculiar method of worship, forgetting that with perfect love, true knowledge is bound to come even unsought, and true love is inseparable from perfect knowledge.

‘Meditation, again, is a constant remembrance of the thing meditated upon, flowing like an unbroken stream of oil poured out from one vessel to another. All bandages break when this kind of remembering is attained in relation to God. Thus it is spoken of in the scriptures regarding constant remembering as a means to liberation. This remembering is of the same nature as seeing because it is of the same meaning as in the passage, ‘When He who is far and near is seen, the bonds of the heart are broken, all doubts vanish, and all effects of work disappear.’ He who is near can be seen, but he who is far can only be remembered. Nevertheless, the scripture reminds us that we have to see Him who is near as well as far, indicating to us that the above kind of remembering is as good as seeing. This remembrance, when exalted, assumes the same form as seeing. . . .

Worship is constant remembering, as seen from the essential scriptures texts. Knowing, which is the same as repeated worship, has been described as constant remembering. . . . Thus, the memory, which has attained the height of what is as good as direct perception, is spoken of in the Shruti as a means of liberation. ‘This Atman is not to be reached through various sciences, nor by intellect, nor by much study of the Vedas. ‘Whomsoever this Atman desires, by him is the Atman attained, unto him this Atman discovers Himself.’ Here, after saying that mere hearing, thinking and meditating are not the means of attaining this Atman, it is said, ‘Whom this Atman desires, by him the Atman is attained.’ By whomsoever this Atman is extremely beloved, he becomes the most beloved of the Atman. So that this beloved may attain the Atman, the Lord Himself helps. For it has been said by the Lord: ‘Those who are constantly attached to Me and worship Me with love — I give that direction to their will by which they come to Me.’ Therefore it is said that to whomsoever this remembering, which is of the same form as direct perception, is very dear; because it is dear to the Object of such memory perception, the Supreme Atman desires him. By him, the Supreme Atman is attained. ‘This constant remembrance is denoted by the word Bhakti,’ says Bhagavan Ramanuja in his commentary on the Sutra Athato Brahma-jijnasa (Hence follows a dissertation on Brahman.).

‘In commenting on the Sutra of Patanjali, Ishvara pranidhanadva, i.e. ‘Or by the worship of the Supreme Lord’ — Bhoja says, ‘Pranidhana is that sort of Bhakti in which, without seeking results, such as sense-enjoyments etc., all works are dedicated to that Teacher of teachers.’ Bhagavan Vyasa also, when commenting on the same, defines Pranidhana as ‘the form of Bhakti by which the mercy of the Supreme Lord comes to the Yogi, and blesses him by granting him his desires.’ According to Shandilya, ‘Bhakti is intense love to God.’ The best definition is, however, that given by the king of Bhaktas, Prahlada: ‘That deathless love which the ignorant have for the fleeting objects of the senses — as I keep meditating on Thee — may not that love slip away from my heart!’

Love! For whom? For the Supreme Lord, Ishvara. Love for any other being, however great, cannot be Bhakti; for, as Ramanuja says in his Shri Bhashya, quoting an ancient Acharya, i.e. a great teacher: ‘From Brahma to a clump of grass, all things that live in the world are slaves of birth and death caused by Karma; therefore they cannot be helpful as objects of meditation, because they are all in ignorance and subject to change.’

In commenting on the word Anurakti used by Shandilya, the commentator Svapneshvara says that it means Anu, after, and Rakti, attachment, i.e. the attachment which comes after the knowledge of the nature and glory of God; else, a blind attachment to anyone, e.g. to wife or children, would be Bhakti. We clearly see, therefore, that Bhakti is a series or succession of mental efforts at religious realisation, beginning with ordinary worship and ending in a supreme intensity of love for Ishvara, the Supreme Ruler.’

On Jnana Yoga

All souls are playing, some consciously, some unconsciously. Religion is learning to play consciously. The same law which holds good in our worldly life also holds good in our religious life and the life of the cosmos. It is one; it is universal. It is not that religion is guided by one law and the world by another. The flesh and the devil are but degrees of difference from God Himself.

Theologians, philosophers, and scientists in the West are ransacking everything to get proof that they live afterwards! What a storm in a teacup! There are much higher things to think of. What silly superstition is this, that you ever die! It requires no priests, spirits, or ghosts to tell us that we shall not die. It is the most self-evident of all truths. No man can imagine his own annihilation. The idea of immortality is inherent in man.

Wherever there is life, with it, there is death. Life is the shadow of death, and death is the shadow of life. The line of demarcation is too fine to determine, too difficult to grasp, and most difficult to hold on to. I do not believe in eternal progress, that we are growing ever and ever in a straight line. It is too nonsensical to believe. There is no motion in a straight line. A straight line infinitely projected becomes a circle. The force sent out will complete the circle and return to its starting place. There is no progress in a straight line. Every soul moves in a circle, as it were, and will have to complete it; no soul can stay down; there will come a time when it will have to go upwards. It may start straight down, but it has to take the upward curve to complete the circuit. We are all projected from a common centre, which is God, and will come back after completing the circuit to the centre from which we started. Each soul is a circle. The centre is where the body is, and the activity is manifested there. You are omnipresent, though you have the consciousness of being concentrated in only one point. That point has taken up particles of matter and formed them into a machine to express itself. That through which it expresses itself is called the body. You are everywhere. When one body or machine fails you, the centre moves on and takes up other particles of matter, finer or grosser, and works through them. Here is man. And what is God? God is a circle with circumference nowhere and centre everywhere. Every point in that circle is living, conscious, active, and equally working. With our limited souls, only one point is conscious, and that point moves forward and backward. The soul is a circle whose circumference is nowhere (limitless) but whose centre is in some body. Death is but a change of centre. God is a circle whose circumference is nowhere, and whose centre is everywhere. When we can get out of the limited centre of the body, we shall realise God, our true Self.

A tremendous stream is flowing towards the ocean, carrying little bits of paper and straw hither and thither on it. They may struggle to go back, but they must flow down to the ocean in the long run. So you and I and all nature are like these little straws carried in mad currents toward that Ocean of Life, Perfection, and God. We may struggle to go back or float against the current and play all sorts of pranks, but in the long run, we must go and join this great ocean of Life and Bliss.

Jnana (knowledge) is ‘creedlessness,’ but that does not mean it despises creeds. It only means that a stage above and beyond creeds has been gained. The Jnani (true philosopher) strives to destroy nothing but to help all. All rivers roll their waters into the sea and become one. So all creeds should lead to Jnana and become one. Jnana teaches that the world should be renounced but not, on that account, abandoned. To live in the world and not to be of it is the true test of renunciation. I cannot see how it can be otherwise than that all knowledge is stored up in us from the beginning. If you and I are little waves on the ocean, then that ocean is the background.

There is no difference between matter, mind, and Spirit. They are only different phases of experiencing the One. This very world is seen by the five senses as matter, by the very wicked as hell, by the good as heaven, and by the perfect as God. We cannot bring it to sense demonstration that Brahman is the only real thing, but we can point out that this is the only conclusion that one can come to. For instance, there must be this oneness in everything, even in common things. There is human generalisation, for example. We say that all the variety is created by name and form; yet it is nowhere to grasp and separate it. We can never see names or forms, or causes standing by themselves. So this phenomenon is Maya — something which depends on the noumenon and apart from it has no existence. Take a wave in the ocean. That wave exists so long as that quantity of water remains in wave form, but as soon as it goes down and becomes the ocean, the wave ceases to exist. But the whole mass of water does not depend so much on its form. The ocean remains, while the waveform becomes absolute zero.

The real is one. It is the mind which makes it appear as many. When we perceive diversity, the unity has gone; as soon as we perceive unity, the diversity has vanished. Just as in everyday life, when you perceive unity, you do not perceive diversity. In the beginning, you start with unity. It is a curious fact that a Chinaman will not know the difference in appearance between one American and another, and you will not know the difference between different Chinamen. It can be shown that it is the mind which makes things knowable. It is only things which have certain peculiarities that bring themselves within the range of the known and knowable. That which has no qualities is unknowable. For instance, there is some external world, X, unknown and unknowable. When I look at it, it is X plus mind. When I want to know the world, my mind contributes three-quarters of it. The internal world is Y plus mind, and the external world X plus mind. All differentiation in either the external or internal world is created by the mind, and that which exists is unknown and unknowable. It is beyond the range of knowledge, and that which is beyond the range of knowledge can have no differentiation. Therefore this X outside is the same as the Y inside, and therefore the real is one.

God does not reason. Why should you reason if you know? It is a sign of weakness that we have to go on crawling like worms to get a few facts, and then the whole thing tumbles down again. The Spirit is reflected in the mind and in everything. It is the light of the Spirit that makes the mind sentient. Everything is an expression of the Spirit; the minds are so many mirrors. What you call love, fear, hatred, virtue, and vice are all reflections of the Spirit. When the reflector is base, the reflection is bad. The real Existence is without manifestation. We cannot conceive It because we should have to conceive through the mind, which is itself a manifestation. Its glory is that It is inconceivable. We must remember that in life, the lowest and highest vibrations of light we do not see, but they are the opposite poles of existence. There are certain things which we do not know now but which we can know. It is due to our ignorance that we do not know them. There are certain things which we can never know because they are much higher than the highest vibrations of knowledge.

We are the Eternal all the time, although we cannot know it. Knowledge will be impossible there. The very fact of the limitations of the conception is the basis for its existence. For instance, there is nothing so certain in me as my Self; and yet I can only conceive of it as a body and mind, as happy or unhappy, as a man or a woman. At the same time, I try to conceive of it as it really is and find that there is no other way of doing it but by dragging it down, yet I am sure of that reality. ‘No one, O beloved, loves the husband for the husband’s sake, but because the Self is there. It is in and through the Self that she loves the husband. No one, O beloved, loves the wife for the wife’s sake, but in and through the Self.’ And that Reality is the only thing we know because in and through It, we know everything else, yet we cannot conceive of It. How can we know the Knower? If we knew It, It would not be the knower but the known; It would be objectified.

The man of highest realisation exclaims, ‘I am the King of kings; there is no king higher than I; I am the God of gods; there is no God higher than I! I alone exist, One without a second.’ This monistic idea of the Vedanta seems to many, of course, very terrible, but that is on account of superstition.

We are the Self, eternally at rest and at peace. We must not weep; there is no weeping for the Soul. We, in our imagination, think that God is weeping on His throne out of sympathy. Such a God would not be worth attaining. Why should God weep at all? To weep is a sign of weakness, of bondage.

Seek the Highest, always the Highest, for in the Highest is eternal bliss. If I am to hunt, I will hunt the lion. If I am to rob, I will rob the treasury of the king. Seek the Highest.

Oh, One that cannot be confined or described! One that can be perceived in our heart of hearts! One beyond all compare, beyond limit, unchangeable like the blue sky! Oh, learn the All, holy one I Seek for nothing else!

Where changes of nature cannot reach, thought beyond all thought, Unchangeable, Immovable; whom all books declare, all sages worship; Oh, holy one, seek for nothing else!

Beyond compare, Infinite Oneness! No comparison is possible. Water above, water below, water on the right, water on the left; no wave on that water, no ripple, all silence, all eternal bliss. Such will come to thy heart. Seek for nothing else!

Why weepest thou, brother? There is neither death nor disease for thee. Why weepest thou, brother? There is neither misery nor misfortune for thee. Why weepest thou, brother? Neither change nor death was predicated for thee. Thou art Existence Absolute.

I know what God is — I cannot speak Him to you. I know not what God is — how can I speak Him to you? But seest thou not, my brother, that thou art He, thou art He? Why go seeking God here and there? Seek not, and that is God. Be your own Self.

Thou art Our Father, our Mother, our dear Friend. Thou bearest the burden of the world. Help us to bear the burden of our lives. Thou art our Friend, our Lover, our Husband, Thou art ourselves!

Raja Yoga – An Introduction

The science of Raja-Yoga, in the first place, proposes to give us such a means of observing the internal states. The instrument is the mind itself. The power of attention, when properly guided, and directed towards the internal world, will analyse the mind and illumine facts for us. The powers of the mind are like rays of light dissipated; when they are concentrated, they illumine. This is our only means of knowledge. Everyone is using it, both in the external and the internal world; but for the psychologist, the same minute observation has to be directed to the internal world, which the scientific man directs to the external; and this requires a great deal of practice. From childhood on, we have been taught only to pay attention to things external but never to things internal; hence most of us have nearly lost the faculty of observing the internal mechanism. To turn the mind as it were, inside, stop it from going outside, and then to concentrate all its powers, and throw them upon the mind itself, in order that it may know its own nature, analyse itself, is very hard work. Yet that is the only way to do anything, which will be a scientific approach to the subject.

What is the use of such knowledge? In the first place, knowledge itself is the highest reward of knowledge, and secondly, there is also utility in it. It will take away all our misery. When by analysing his own mind, a man comes face to face, as it were, with something which is never destroyed, something which is, by its own nature, eternally pure and perfect, he will no more be miserable, no more unhappy. All misery comes from fear, from unsatisfied desire. Man will find that he never dies, and then he will have no more fear of death. When he knows that he is perfect, he will have no more vain desires, and both these causes being absent, there will be no more misery — there will be perfect bliss, even while in this body.

There is only one method by which to attain this knowledge, which is called concentration. The chemist in his laboratory concentrates all the energies of his mind into one focus and throws them upon the materials he is analysing, and so finds out their secrets. So the astronomer concentrates all the energies of his mind and projects them through his telescope upon the skies, the stars, the sun, and the moon giving up their secrets to him. The more I can concentrate my thoughts on the matter I am talking to you, the more light I can throw upon you. You are listening to me; the more you concentrate your thoughts, the more clearly you will grasp what I have to say.

How has all the knowledge in the world been gained but by the concentration of the powers of the mind? The world is ready to give up its secrets if we only know how to knock, how to give it the necessary blow. The strength and force of the blow come through concentration. There is no limit to the power of the human mind. The more concentrated it is, the more power is brought to bear on one point; that is the secret.

It is easy to concentrate the mind on external things; the mind naturally goes outwards, but not so in the case of religion, psychology, or metaphysics, where the subject and the object are one. The object is internal, the mind itself is the object, and it is necessary to study the mind itself — the mind studying the mind. We know that there is the power of the mind called reflection. I am talking to you. At the same time, I am standing aside, as it were, a second person, and knowing and hearing what I am talking about. You work and think simultaneously while a portion of your mind stands by and sees what you are thinking. The powers of the mind should be concentrated and turned back upon itself. As the darkest places reveal their secrets before the sun’s penetrating rays, so will this concentrated mind penetrate its innermost secrets. Thus we will come to the basis of belief, the real genuine religion.

We will perceive for ourselves whether we have souls, whether life is of five minutes or of eternity, and whether there is a God in the universe or more. It will all be revealed to us. This is what Raja-Yoga teaches. The goal of all its teaching is how to concentrate the minds, then how to discover the innermost recesses of our minds, then how to generalise their contents and form our conclusions from them. It, therefore, never asks the question of what our religion is, whether we are Deists or Atheists, whether Christians, Jews, or Buddhists. We are human beings; that is sufficient. Every human being has the right and the power to seek religion. Every human has the right to ask the reason and to have his question answered inwardly if he only takes the trouble.

According to the Raja-Yogi, the external world is but the gross form of the internal or subtle. The finer is always the cause, the grosser the effect. So the external world is the effect, the internal the cause. In the same way, external forces are simply the grosser parts, of which the internal forces are the finer. The man who has discovered and learned how to manipulate the internal forces will get the whole of nature under his control. The Yogi proposes to himself no less a task than to master the whole universe, to control the whole of nature. He wants to arrive at the point where what we call ‘nature’s laws’ will have no influence over him, where he will be able to get beyond them all. He will be the Master of the whole of nature, internal and external. The progress and civilisation of the human race simply mean controlling this nature.

The end and aim of all science is to find the unity, the One out of which the manifold is being manufactured, that One existing as many. Raja-Yoga proposes to start from the internal world, to study internal nature, and through that, control the whole — both internal and external. It is a very old attempt. India has been its special stronghold, but it was also attempted by other nations. In Western countries, it was regarded as mysticism, and people who wanted to practice it were either burned or killed as witches and sorcerers. In India, for various reasons, it fell into the hands of persons who destroyed ninety percent of the knowledge and tried to make a great secret of the remainder. In modern times many so-called teachers have arisen in the West worse than those of India, because the latter knew something, while these modern exponents know nothing.

The Yogi proposes to attain that fine state of perception in which he can perceive all the mental states. There must be a clear mental perception of all of them. One can perceive how the sensation is travelling, how the mind is receiving it, how it is going to the determinative faculty, and how this gives it to Purusha. Each science requires certain preparations and its method, which must be followed before it can be understood.

Certain regulations as to food are necessary; we must use that food which brings us the purest mind. If you go into a menagerie, you will find this demonstrated at once. You see the elephants, huge animals, but calm and gentle, and if you go towards the cages of the lions and tigers, you find them restless, showing how much difference has been made by food. All the forces that are working in this body have been produced out of food; we see that every day. If you begin to fast, first, your body will get weak, and the physical forces will suffer; then, after a few days, the mental forces will suffer also. First, memory will fail. Then comes the point when you are not able to think, much less pursue any course of reasoning. Therefore, we have to take care of what sort of food we eat at the beginning, and when we have enough strength when our practice is well advanced, we need not be so careful in this respect. While the plant is growing, it must be hedged around, lest it is injured, but when it becomes a tree, the hedges are removed. It is strong enough to withstand all assaults.

A Yogi must avoid the two extremes of luxury and austerity. He must not fast nor torture his flesh. He who does so, says the Gita, cannot be a Yogi: He who fasts, he who keeps awake, he who sleeps much, he who works too much, he who does no work, none of these can be a Yogi (Gita, VI, 16).

The following article was written by Sister Nivedita, one of Swami Vivekananda’s closest devotees, in her book ‘The Master As I Saw Him.’

SWAMI VIVEKANANDA AND MOTHER-WORSHIP

The story of the glimpses I caught of this part of Swami’s life would be incomplete if it contained no mention of his worship of the Mother. Spiritually speaking, I have always felt that there were two elements in his consciousness. Undoubtedly he was born a Brahmajnani, as Ramakrishna Paramahamsa so frequently insisted. When he was only eight years old, sitting at his play, he had already developed the power of entering Samadhi. The religious ideas he naturally gravitated towards were highly abstract and philosophical, the reverse of those commonly referred to as ‘idolatrous.’ In his youth, and presumably, when he had already been some time under the influence of Sri Ramakrishna, he became a formal member of the Sadharan Brahmo Samaj. In England and America he was never known to preach anything that depended on a particular form. The realisation of Brahman was his only imperative, the Advaita philosophy his only system of doctrine, the Vedas and Upanishads his sole scriptural authority.

And yet, side by side with this, it is also true that in India, the word ‘Mother’ was forever on his lips. He spoke of Her, as we of one deeply familiar in the household life. He was constantly preoccupied with Her. Like other children, he was not always good. Sometimes he would be naughty and rebellious. But always to Her. Never did he attribute to any other the good or evil that occurred. On a certain solemn occasion, he entrusted to a disciple a prayer that in his own life had acted as a veritable charm. ‘And mind!’ he added suddenly, turning with what was almost fierceness upon the receiver, ‘make Her listen to you when you say it! None of that cringing to Mother! Remember!’ Now and then, he would break out with some new fragment of description. The right hand raised in blessing, the left holding the sword — ‘Her curse is a blessing!’ would be the sudden exclamation that ended a long reverie. Or becoming half-lyric in the intensity of his feeling, ‘Deep in the heart of hearts of Her own, flashes the blood-red knife of Kali. Worshippers of the Mother are they, from their birth, in Her incarnation of the sword!’ From him was gathered, in such moments as these, almost every line and syllable of a certain short psalm, called the ‘Voice of the Mother,’ which I wrote and published about this time.

‘I worship the Terrible!’ he was continually saying,— and once, ‘It is a mistake to hold that with all men pleasure is the motive. Quite as many are born to seek after pain. Let us worship the Terror for Its own sake.’

He had a whole-hearted contempt for what he regarded as squeamishness or mawkishness. He wasted few words on me when I came to him with my difficulties with animal sacrifice in the temple. He made no reference, as he might have done, to the fact that most of us, loudly as we may attack this, have no hesitation in offering animal sacrifice to ourselves. He offered no argument, as he easily might have done, regarding the degradation of the butcher and the slaughterhouse, under the modern system. ‘Why not a little blood to complete the picture?’ was his only direct reply to my objections. And it was with considerable difficulty that I elicited from him, and from another disciple of Sri Ramakrishna, sitting near, the actual facts of the more austere side of Kali-worship, that side which has transcended the sacrifice of others.

He told me, however, that he had never tolerated the blood-offering commonly made to the ‘demons who attend on Kali.’ This was simple devil worship, and he had no place for it. His own effort being constantly to banish fear and weakness from his consciousness and to learn to recognise THE MOTHER as instinctively in evil, terror, sorrow, and annihilation, as in that which makes for sweetness and joy, it followed that the one thing he could not do was any sort of watering-down of the great conception. ‘Fools!’ he exclaimed once — as he dwelt in quiet talk on ‘the worship of the Terrible,’ on ‘becoming one with the Terrible’— ‘Fools! They put a garland of flowers round Thy neck, then start back in terror, and call Thee ‘the Merciful’!’

And as he spoke, the underlying egoism of worship that is devoted to the kind God, to Providence, the consoling Divinity, without a heart for God in the earthquake, or God in the volcano, overwhelmed the listener. One saw that such worship was at its bottom, as the Hindu calls it, merely ‘shop-keeping,’ and one realised the infinitely greater boldness and truth of the teaching that God manifests through evil as well as through good. One saw that the true attitude for the mind and will that are not to be baffled by the personal self was in fact, the determination, in the stern words of the Swami Vivekananda, ‘to seek death, not life, to hurl oneself upon the sword’s point, to become one with the Terrible for evermore!’

It would have been altogether inconsistent with Swami’s idea of freedom to have sought to impose his own conceptions on a disciple. But everything in my past life as an educator had contributed to impress on me now the necessity of taking on the Indian consciousness. The personal perplexity associated with the memory of the pilgrimage to Amarnath was a witness not to forget the strong place which Indian systems of worship held in that consciousness. I set myself, therefore, to enter into Kali worship, as one would set oneself to learn a new language or take birth deliberately, perhaps, in a new race. To this fact, I owe it that I was able to understand as much as I did of our Master’s life and thought. Step by step, glimpse after glimpse, I began to comprehend a little. And in matters religious, he was, without knowing it, a born educator. He never checked a struggling thought. Being with him one day when an image of Kali was brought in, and noticing some passing expression, I suddenly said, ‘Perhaps, Swamiji, Kali is the Vision of Siva! Is She?’ He looked at me for a moment. ‘Well! Well! Express it in your way,’ he said gently, ‘Express it in your own way!’

Another day he was going with me to visit the old Maharshi Devendra Nath Tagore, in the seclusion of his home in Jorasanko. Before we started, he questioned me about a death scene at which I had been present the night before. I told him eagerly of the sudden realisation that had come to me that religions were only languages, and we must speak to a man in his own language. His whole face lighted up at the thought. ‘Yes!’ he exclaimed, ‘And Ramakrishna Paramahamsa was the only man who taught that! He was the only man who ever had the courage to say that we must speak to all men in their own language!’

Yet there came a day when he found it necessary to lay down with unmistakable clearness his own position in the matter of Mother-worship. I was about to lecture at the Kalighat, and he came to instruct me that if any foreign friends should wish to be present, they were to remove their shoes and sit on the floor like the rest of the audience. In that Presence, no exceptions were to be made. I myself was to be responsible for this.[ 1]

After saying all this, however, he lingered before going, and then, making a shy reference to Colonel Hay’s poem of the ‘Guardian Angels,’ he said, ‘That is precisely my position about Brahman and the gods! I believe in Brahman and the gods, and not in anything else!’

He was evidently afraid that my intellectual difficulty would lie where his own must have done, in the incompatibility of the exaltation of one definite scheme of worship with the highest Vedantic theory of Brahman. He did not understand that to us who stood about him, he was himself the reconciliation of these opposites and the witness to the truth of each. Following up this train of thought, therefore, he dropped into a mood of half-soliloquy and sat for a while talking disjointedly, answering questions, trying to make himself clear, yet always half-absorbed in something within, as if held by some spell he could not break.

‘How I used to hate Kali!’ he said, ‘And all Her ways! That was the ground of my six years’ fight — that I would not accept Her. But I had to accept Her at last! Ramakrishna Paramahamsa dedicated me to Her, and now I believe that She guides me in every little thing I do, and does with me what She will! Yet I fought so long! I loved him, you see, and that was what held me. I saw his marvellous purity; I felt his wonderful love. His greatness had not dawned on me then. All that came afterwards, when I had given in. At that time, I thought of him as a brain-sick baby, always seeing visions and the rest. I hated it. And then, I too had to accept Her!’

‘No, the thing that made me do it is a secret that will die with me. I had great misfortunes at that time. It was an opportunity. She made a slave of me. Those were the very words — ‘a slave of you.’ And Ramakrishna Paramahamsa made me over to Her… Strange! He lived only two years after doing that, and most of the time he was suffering. Not more than six months did he keep his health and brightness.

‘Guru Nanak was like that, you know, looking for the one disciple to whom he would give his power. And he passed over all his own family — his children were as nothing to him — till he came upon the boy to whom he gave it, and then he could die.