Overview and Significance

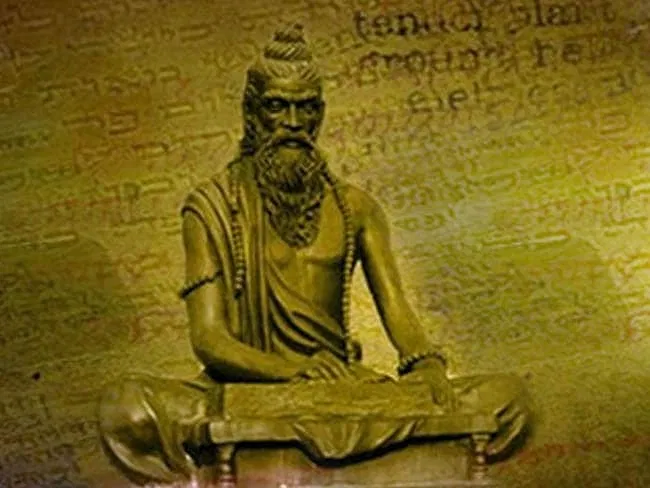

Siddha Patanjali is a great yogi of the Tamil Shaiva Siddha tradition. He is variously estimated to have lived between the 2nd century B.C. to 4th century A.D. He is one of the great ‘Siddhas’ and revered as one of the great saints who rendered a lot towards the art of Yoga. He is the author of the Yoga Sutras, one of the greatest works on Yoga. Today, the Yoga Sutras are the most referenced text on yoga, making Patanjali ‘the father of yoga’ in the eyes of many.

Possibly, Patanjali may not be one person, and there could be several Patanjalis in the course of Indian History. The Patanjali Yoga Sutra, also called Patanjala Yoga Darshanam, is a great composition of Yoga, which led to the dawn of today’s yogic beliefs and practices, and is a classic text on Raja Yoga. Beyond the Yoga Sutras, commentaries on other notable works attributed to Patanjali are Mahabhashya, dating from about the second century BCE, a commentary on an authoritative Sanskrit grammar text written by the Indian grammarian, Panini. He was one of those saints who presented metaphysical truths through form of Sanskrit grammar.

Patanjali also authored a medical text called Patanjali Tantra. He is cited, and this text is quoted in many medieval health sciences-related texts. Patanjali is called a medical authority in several Sanskrit texts such as Yogaratnakara, Yoga Ratna Samuccaya, and Padarthavijnana. Another Hindu scholar, also named Patanjali, likely lived in 8th-century CE and wrote a commentary on Charaka Samhita, and this text is called Charakavarttika. According to some modern era Indian scholars such as P.V. Sharma, the two medical scholars named Patanjali may be the same person, but a completely different person from the Patanjali who wrote the Sanskrit grammar classic Mahabhashya.

While modern scholars generally believe this timeline makes it impossible for it to have been the same Patanjali who compiled all these works, many hold a more traditional view that a single Patanjali is indeed responsible for all. Some might think it ridiculous for anyone to believe that a single person could be the author of texts written possibly more than 1,000 years apart. However, Patanjali is also considered by many within the Hindu tradition to be a divine figure. Patanjali continues to be honored with invocations and shrines in some forms of modern postural yoga, such as Iyengar Yoga and Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga.

Life History

Birth and Legends

In the Indian tradition, Patanjali is said to be self-born – swayambhu. He was a highly evolved soul who incarnated of his own will in a human form to help humanity. He is also considered an incarnation of Ananta, the source of all wisdom (Jnana), and Shesha, the thousand-headed ruler of the serpent race, thought to guard the earth’s hidden treasures. Ananta is usually depicted as a couch on which Lord Vishnu reclines. He is the Lord of serpents, and his many heads symbolise Infinity or Omnipresence. Many yogis bow to Ananta before they begin their daily yogic practice.

In one of the legends, Lord Vishnu was seated on Adishesha, the Lord of serpents as His couch, watching the enchanting dance of Lord Shiva. Lord Vishnu was so totally absorbed in the dance of Lord Shiva that His body began to vibrate to its rhythm. This vibration made Him heavier and heavier, causing Adishesha to feel so uncomfortable that he was gasping for breath and was on the point of collapse. The moment the dance came to an end, Lord Vishnu’s body became light again. Adishesha was amazed and asked his Master the cause of these astonishing changes.

The Lord explained that Lord Shiva’s dance, grace, beauty, majesty, and grandeur had created corresponding vibrations in His own body, making it heavy. Marveling at this, Adishesha professed a desire to learn a dance to exalt his Lord. Vishnu then became thoughtful and predicted that soon Lord Shiva would grace Adishesha to write a commentary on grammar and that he would then also be able to devote himself to perfection in the art of dance. Adishesha was overjoyed by these words and looked forward to the descent of Lord Shiva’s grace.

Adishesha then began to meditate to ascertain who would be his mother on earth. In meditation, he had the vision of a yogini named Gonika praying for a worthy son to impart her knowledge and wisdom. He at once realised that she would be a worthy mother for him and awaited an auspicious moment to become her son.

Gonika thought that her earthly life was approaching its end and that her desire to find a worthy son would remain unfulfilled; now, as a last resort, she looked to the Sun God, the living witness of God on earth, and prayed to Him to fulfill her desire. She took a handful of water as a final oblation to Him, closed her eyes, and meditated on the Sun. As she was about to offer the water, she opened her eyes and looked at her palms. To her surprise, she saw a tiny snake moving in her palms, who soon took on a human form. This tiny male human being prostrated to Gonika and asked her to accept him as her son. She did and named him Patanjali because her hands had been in the prayerful gesture (anjali) and had fallen (pat) from heaven.

Another incident is said to have happened in Chidambaram (also known as Thillai), located about a hundred miles from Madras. Chidambaram is one of the holiest temples in India. In this temple, Lord Nataraja is present in his cosmic-dancing form. The story goes that once in Darukavanam, Shiva wished to teach a lesson to the Rishis who were proud of their learning. Shiva took the form of a mendicant with a begging bowl in hand, accompanied by Vishnu disguised as Mohini. The sight of this beautiful pair attracted the rishi patnis (wives of the Rishis).

The Rishis grew angry and tried to destroy the pair. They performed a sacrificial fire and raised a tiger from the fire, which sprang at Shiva. Shiva peeled off the skin of the tiger and wrapped it around his waist. Then again, the Rishis sent a poisonous serpent, and Shiva tied it around his neck. Then the Rishis sent against Shiva an Apasmara Purusha, Muyalaka, whom Lord Shiva crushed by pressing him to the ground with his foot.

After this, the Rishis confessed defeat, and Shiva started to dance before all the Gods and Rishis. Lord Adishesha heard the description of Shiva’s dance at Darukavanam from Vishnu and requested Vishnu to allow him to witness the dance himself. Vishnu agreed to this. Adishesha performed penance and prayed to Shiva to allow him to see the dance. Being pleased with his penance, Shiva appeared to him and promised that he would dance at Tillai (Chidambaram). Accordingly, Adishesha was born as a human being, as Patanjali, and went to the forest of Tillai.

At this time, a certain sage, Vyaghrapada, also lived in this forest. Vyaghrapada was the son of Madhyandina Rishi, who lived on the banks of the Ganga. He came to the South under his father’s directions and started praying to the Swayambhulinga under a banyan tree near a tank in the Tillai forest.

He used to collect flowers for puja, and he prayed for the boon of getting tiger’s feet and claws so that he could easily climb up the trees and pluck plenty of flowers. He also prayed for the eyes of bees to collect the flowers before any bee could taste the honey in them. His prayer for these two blessings was granted, and since he had the feet of a tiger, he was called Vyaghrapada.

Each constructed his hermitage, Patanjali at Ananteeswaram and Vyaghrapada at Thirupuleeswaram in Chidambaram. They started worshipping Shiva in the form of the Swayambhu Linga (the linga that manifested on its own) in the Tillai forest. Days passed, and when the time came for Shiva to give them Darshan, the guardian Goddess of the place, Kalika Devi, interfered and did not allow Shiva to give His Darshan.

Shortly afterward, Shiva and Devi agreed that they should participate in a dance contest and that the winner should have undisputed possession of Tillai. So, the dance started. At one moment during the dance, the Lord’s earrings fell, but the Lord took them up from the floor in such a way that nobody could notice the loss and the recovery. This dance is called Urdhva Tandavam, in which Shiva defeated Kalika Devi.

Now Nataraja performed the Ananda Tandavam, i.e., the Dance of Bliss, in the presence of Sivakamasundari and all the Gods and Rishis, and at the same time fulfilled the wish of the two devotees, Patanjali and Vyaghrapada, by allowing them to witness it and thus satisfying them.

Another story tells that once upon a time, Nandi, Shiva’s carrier, would not allow Patanjali Muni to have Darshan of Lord Shiva (Nataraja of Chidambaram). To reach Lord Shiva, Patanjali, with his mastery over grammatical forms, spontaneously composed a prayer in praise of the Lord without using any extended (Dirgha) syllable (without Charana and Shringa), i.e., leg and horn, to tease Nandi.

Shiva was quickly pleased, gave Darshan to the devotee, and danced to the lilting tune of this song. These three short legends throw some light upon Patanjali and his greatness. Today, unfortunately, even Patanjali’s lineage does not appear to exist anymore.

The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali is a collection of Sanskrit sutras (aphorisms) on the theory and practice of yoga – 195 sutras (according to Vyasa and Krishnamacharya) and 196 sutras (according to other scholars, including BKS Iyengar). The Yoga Sutras was compiled sometime between 500 BC and AD400 by the sage Patanjali in India, who synthesiaed and organised knowledge about yoga from much older traditions. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali was the most translated ancient Indian text in the medieval era, translated into about forty Indian languages and two non-Indian languages: Old Javanese and Arabic. The text fell into relative obscurity for nearly 700 years from the 12th to 19th century. It made a comeback in the late 19th century due to the efforts of Swami Vivekananda, the Theosophical Society, and others. It gained prominence again as a comeback classic in the 20th century.

Sutra, usually translated in English as ‘an aphorism,’ literally means ‘a thread.’ Like a thread in a rosary (Mala) threads all the beads and prevents them from falling apart, in the same way, these Sutras act as a thread that is weaving all the beautiful divine truths and concepts that are called Yoga collectively and prevents them from falling apart. So, the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali are like a rosary (Mala) in which the beads are the divine truths.

Darshanam, usually translated in English as ‘philosophy’ (i.e., love for wisdom), literally means ‘a vision, a realization.’ Truths described in the classical text of the Yoga Sutras are not just existing in theory, they are not just a hypothesis, but they have been ‘seen’ by those great Seers, they have realised them. They had integrated those truths into their own lives.

As written by David Gordon White in his book ‘The Yoga Sutra of Patanjali: A Biography,’: ‘”Patanjali” is listed as the name of one of the twenty-six mythical divine serpents in several Puranas.‘ The major Puranas (eighteen in number) are ancient Hindu texts said to have been composed by the sage Veda Vyasa.

The Vishnudharmottara Purana, a supplement to the Vishnu Purana, says the ‘image of Patanjali’s Yoga teaching should have the form of Ananta.‘ Ananta, described in Hindu legend as the divine Lord of Serpents, is said to hold all of the universe’s planets on his 1,000 cobra hoods.

Noticeably, the Vishnudharmottara Purana, which dates to the sixth century, connects the ‘yoga’ Patanjali and the ‘Ananta’ Patanjali, as if they are one and the same.

Taking note of this, King Bhoja — an 11th-century patron of arts, literature, and science — wrote in the introduction of his ‘Royal Sun’ commentary of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras (in Sanskrit):

Yōgēna cittasya padēna vācāṁ malaṁ śarīrasya ca vaidyakēna. Yōpākarōttaṁ pravaraṁ munīnāṁ patañjaliṁ prāñjalirānatōsmi

‘I bow with folded hands to Patanjali, the best of sages, who removed the impurities of the mind through yoga; the impurities of speech through grammar; and the impurities of the body through medicine. To he whose upper body has a human form, who holds a conch and a wheel, who is white and has a thousand heads, to that Patanjali, I offer obeisance.‘

King Bhoja’s praise of Patanjali not only recognizes the ‘yoga’ and ‘Ananta’ Patanjali to be the same person, but also the ‘grammar’ and ‘Ayurveda’ Patanjali. Though there are other instances of the four-in-one Patanjali portrayal throughout history, as the centuries have gone by, Bhoja’s prayer has become one of the more well-known and recited examples.

Patanjali defined yoga as Chitta Vritti Nirodha: if you still the modifications and activity of the mind, you are in yoga. Everything has become one in your consciousness. We may be pursuing many things in our lives and going through processes that we call achievements, but to go beyond the modifications of the mind is the most fundamental and at the same time the highest achievement one can attain. This releases a human being from what he is seeking – from what is within and what is outside – from everything. If only he stills his mind, he becomes an ultimate possibility. The mind becomes a plain mirror, not a wavy mirror. A wavy mirror will distort one’s whole perception of life. At least if you do not look at it, you may have some idea how you are, but if you look at it every day, it will give you a completely distorted vision of everything.

Right now, most human beings are using their mind only between their memory and imagination. Memory and imagination are not two separate things. Memory is the accumulated past; imagination is an exaggerated version of that. If you bring your mind to a state where you are neither contaminated by memory nor deluded by imagination, then it is a brilliant, penetrative mind. It sees everything there is to see – life and its source. For the survival process, your memory and imagination are good enough. Still, if you want to explore other dimensions of life, then memory and imagination are not sufficient because they are only recycling your past. Once you recycle your history, there is a pattern to your life. And it is an unbreakable pattern if your mind is just engaged in memory and imagination.

Once a pattern traps you, it does not matter who created it; it is a kind of slavery. Essentially, realising that one is trapped in psychological realities and missing out on the existential experience of the grandeur of creation is the first step towards liberation.

This is the reason why, of all the beautiful ways in which it could be expressed, Patanjali chose the description Chitta Vritti Nirodha for yoga. This method can take you towards your liberation or realisation.

Dictating the Mahabhashya

After teaching and guiding students for a long time, Patanjali decided to undertake a thousand-year-long meditation practice. Until then, he had been teaching the Mahabhashya orally but decided to put it into writing before going into solitude. He discussed his plan for doing this with a thousand of his select students.

He explained that he would dictate the text to them while sitting behind a circular curtain. He would give the dictation under stringent conditions: The students must not attempt to see who was speaking from behind the curtain; they must focus only on what was dictated to them, and pay no attention to what was being dictated to those around them; and finally, they must not get up from their seats until the entire session was complete. Patanjali explained that a violation of any of these rules would have fatal consequences. Further, that a mistake committed by any one of the students would have dire consequences for all because they all constituted one unified collective consciousness.

A large circular curtain was erected around Patanjali. With pen and paper in hand, all thousand students sat in a circle facing the curtain. As soon as Patanjali invoked his yoga shakti, each student felt as if he were sitting directly in front of the Master. When dictation began, the students had the overwhelming realisation that there was more than one Patanjali behind the curtain: as if there were a thousand, one for each student.

As fate would have it, after a while, one of the students needed to go to the bathroom so badly that he got up and left. Another student could not manage his curiosity and lifted the curtain. There he saw a gigantic snake with a body of fire. With its thousand faces, it was giving a separate dictation to each student. In the next instant, the fire confined to the inside of the curtain spread and incinerated every student—all except the one who had left his seat.

Patanjali withdrew his yoga shakti, and the radiant snake with its thousand heads was reabsorbed into his body. While the Master was reflecting on the catastrophe brought about by the student’s careless behaviour, he saw to his surprise that one student remained alive and unharmed. When Patanjali learned that this student had left and returned after the all-consuming fire had been reabsorbed into his body, he found himself facing a dilemma. By leaving his seat before the dictation was completed, this student had violated one of the conditions and therefore must reap the consequences and be incinerated like the other nine hundred and ninety-nine. But the other students had met their fate when Patanjali’s consciousness had transcended his individual human identity. Now he was fully aware of himself as a teacher, and his student stood before him. If the student were not incinerated, it would be a violation of the conditions. But if he did not protect his student from being incinerated, then Patanjali himself would be violating the fundamental principle of a teacher’s unconditional love, protection, and guidance.

The Ingenious Solution

After weighing all the pros and cons, Patanjali decided to help the student leave his body through spontaneous combustion. Then Patanjali passed on the complete knowledge of the Mahabhashya to this disembodied soul and assigned him a large banyan tree as a locus for his consciousness. Patanjali also blessed this student with an unfailing memory and the capacity to communicate the knowledge of the Mahabhashya by writing on the leaves of the banyan tree. The blessing stipulated that as soon as he had transmitted the entire text in one uninterrupted session to someone with the stamina to keep his seat until the transmission was complete, the student would attain freedom from using the banyan tree as his body. Patanjali then vanished for a thousand years.

Patanjali is much more than the master who codified the Yoga Sutras. Time passed as the student waited in the banyan tree. Eventually, a great yogi and scholar, Govinda Swami, arrived at the base of the tree. His intuition told him he had found the tree he had been seeking, and the student realised Govinda Swami was the scholar he had been awaiting. Thus, the transmission began. Through his sheer intention, the student engraved the Mahabhashya on the banyan leaves and dropped them before Govinda Swami, who in turn arranged them in the proper order. But as the leaves were falling from the tree, a herd of goats rushed in to eat the leaves. Govinda Swami tried his best to protect them, but alas, some of them were eaten. Thus, even in today’s printed version of The Mahabhashya, we find in brackets aja bhakshitam etat, ‘It was eaten by goats.’

This story demonstrates that Patanjali is much more than the Master who codified the Yoga Sutras. He is the very embodiment of the Yoga Sutras and the long list of siddhis described therein. Patanjali’s immortality, his identity as the perennial source of knowledge, and his love for reviving wisdom and guiding students on the path leading to the summum bonum of life are further demonstrated when a thousand years later, he returns as Govinda Pada to transmit the highest wisdom to Adi Shankaracharya.

Samadhi

After writing the scriptures, he then meets his mother, and after taking her blessings and being satisfied that his mission is accomplished, he goes to the Rameshwaram temple. Rameshwaram temple has many temples within it. On the temple entrance, a large statue of Patanjali faces Vyagrapada in anjali-mudra displaying his reverence to Lord Shiva. On a wall near the entrance of the shiva mandapa is the list of self-initiated gurus who have served at the temple. Patanjali is listed as the third of eighteen. The Rameshwaram temple has a small, enclosed courtyard with a well; tradition holds that Patanjali meditated here in silence for many years. As time passed, he became increasingly translucent until he became nearly transparent, then one day, He was seen no more. He was absorbed into eternity as he dissolved from sight in this world. His samadhi houses a holy fire, a symbol of his life and transmutation, and he attains Jeeva samadhi there.

Tradition and Gurus

Patanjali is one of the 18 Siddhas in the Tamil Siddha (Shaiva) tradition. Patanjali learned yoga and other disciplines from the famous Yogic Guru, Nandhi Deva (the divine bull of Lord Shiva). Nandhi is one of the 18 Yoga Siddhas (perfected ones) initiated by Lord Shiva. Nandhi Deva’s disciples include Patanjali, Dakshinamoorthy, Thirumoolar, Romarishi, and Sattaimuni.

Teachings

https://www.arlingtoncenter.org/Sanskrit-English.pdf – Yoga Sutras Pdf

The Yoga Sutras are a composite of various traditions. The levels of samadhi taught in the text resemble the Buddhist jhanas. According to Feuerstein, the Yoga Sutras are a condensation of two different traditions, namely ‘eight limb yoga’ (aṣṭaṅga yoga) and action yoga (Kriya yoga). The kriya yoga part is contained in chapter 1, chapter 2 sutras 1-27, chapter 3 except sutra 54, and chapter 4. The ‘eight limb yoga’ is described in chapter 2 sutras 28–55, and chapter 3 sutras 3 and 54.

Patanjali divided his Yoga Sutras into four chapters or books (Sanskrit Pada), containing all 196 aphorisms, divided as follows:

Samadhi Pada (51 sutras). Samadhi refers to a state of direct and reliable perception (pramaṇa) where the yogi’s self-identity is absorbed into pure consciousness, collapsing the categories of witness, witnessing, and witnessed. Samadhi is the primary technique the yogi learns by which to dive into the depths of the mind to achieve Kaivalya (liberation). The author describes yoga and then the nature and the means of attaining samadhi.

This chapter contains the famous definitional verse: ‘Yogaś citta-vritti-nirodhaḥ‘ (‘Yoga is the restraint of fluctuations/patterns of consciousness’)

Sadhana Pada (55 sutras). Sadhana is the Sanskrit word for ‘practice’ or ‘discipline.’ Here the author outlines two systems of Yoga: Kriya Yoga and Ashtanga Yoga (Eightfold or Eight Limbed Yoga).

Kriya Yoga in the Yoga Sutras is the practice of three of the Niyamas (duties or observances) of Aṣṭanga Yoga:

Tapas – austerity

Svadhyaya – self-study of the scriptures

Iśvara praṇidhana – devotion to God or pure consciousness

Ashtanga Yoga is the yoga of eight limbs:

Yama – restraints or ethics of behaviour

Niyama – observances

Asana – physical postures

Praṇayama – control of the prana (breath)

Pratyahara – withdrawal of the senses

Dharaṇa – concentration

Dhyana – meditation

Samadhi – absorption

Vibhuti Pada (56 sutras). Vibhuti is the Sanskrit word for ‘power’ or ‘manifestation.’ ‘Supra-normal powers’ (Sanskrit: siddhi) are acquired by the practice of yoga. The combined simultaneous practice of Dharana (concentration), Dhyana (meditation) and Samadhi (absorption) is referred to as Samyama and is considered a tool of achieving various perfections, or Siddhis. The text warns (III.38) that these powers can become an obstacle to the yogi who seeks liberation.

Kaivalya Pada (34 sutras). Kaivalya literally translates to ‘isolation,’ but as used in the Sutras, it stands for emancipation or liberation, used where other texts often employ the term moksha (liberation). The Kaivalya Pada describes the process of liberation and the reality of the transcendental consciousness.

Purpose of yoga

Patanjali begins his treatise by stating the purpose of his book in the first sutra, followed by defining the word ‘yoga’ in his second sutra of Book 1:[43]

योगश्चित्तवृत्तिनिरोधः ॥२॥

yogaś citta-vṛtti-nirodhaḥ

— Yoga Sutras 1.2

This terse definition hinges on the meaning of three Sanskrit terms. I. K. Taimni translates it as ‘Yoga is the inhibition (nirodhaḥ) of the modifications (vṛtti) of the mind (citta).‘

Swami Vivekananda translates the sutra as ‘Yoga is restraining the mind-stuff (Citta) from taking various forms (Vrittis).‘

Bryant states that, to Patanjali, ‘Yoga essentially consists of meditative practices culminating in attaining a state of consciousness free from all modes of active or discursive thought, and of eventually attaining a state where consciousness is unaware of any object external to itself, that is, is only aware of its nature as consciousness unmixed with any other object.‘

- Yamas

Yamas are ethical vows in the Yogic tradition and can be thought of as moral imperatives. The five Yamas listed by Patanjali in Yoga Sutra 2.30 are:

Ahimsa (अहिंसा): Nonviolence, non-harming other living beings through actions and speech

Satya (सत्य): truthfulness, non-falsehood

Asteya (अस्तेय): non-stealing

Brahmacharya (ब्रह्मचर्य): chastity, marital fidelity or sexual restraint

Aparigraha (अपरिग्रह): Non-greed, non-grasping, non-possessiveness

The commentaries on these teachings of Patanjali state how and why each of the above self-restraints help in the personal growth of an individual. For example, in verse II.35, Patanjali states that the virtue of nonviolence and non-injury to others (Ahimsa) leads to the abandonment of enmity. This state leads the yogi to the perfection of inner and outer amity with everyone, everything.

In Sutra 2.31, Patanjali calls the Yamas Mahavratam, which means a Great Vow. Patanjali states that the Yamas’ practice is universal and should not be limited by class, place, time, or circumstances.

- Niyama

The second component of Patanjali’s Yoga path is called niyama, which includes virtuous habits, behaviors, and observances (the ‘dos’). Sadhana Pada Verse 32 lists the niyamas as:

Shaucha (शौच): purity, clearness of mind, speech, and body

Santosha (संतोष): contentment, acceptance of others, acceptance of one’s circumstances as they are to get past or change them, optimism for self.

Tapas (तपस्): literally translates to fire or heat. But in the yogic context, it means persistence, perseverance, austerity.

Svadhyaya (स्वाध्याय): Self-study, self-reflection, introspection of self’s thoughts, speeches and actions, the study of scriptures

Ishvarapranidhana (ईश्वरप्रणिधान): contemplation of the Ishvara (God/Supreme Being, Brahman, True Self, Unchanging Reality).

- Asana

Patanjali begins the discussion of Asana (आसन, meditation posture) by defining it in verse 46 of Book 2, as follows,

स्थिरसुखमासनम् ॥४६॥

sthira sukham asanam.

Translation 1: An asana is what is steady and pleasant.

Translation 2: Motionless and Agreeable form (of staying) is Asana (yoga posture).

— Yoga Sutras II.

Asana is thus a (meditation) posture that one can hold for some time, staying relaxed, steady, comfortable, and motionless. Patanjali does not list any specific asana, except the terse suggestion, ‘posture one can hold with comfort and motionlessness.’ Araṇya translates verse II.47 as, ‘asanas are perfected over time by relaxation of effort with meditation on the infinite‘; this combination and practice stop the quivering of the body.

The Bhasya commentary attached to the Sutras, now thought to be by Patanjali himself, suggests twelve seated meditation postures: Padmasana (lotus), Virasana (hero), Bhadrasana (glorious), Svastikasana (lucky mark), Dandasana (staff), Sopas Rasayana (supported), Paryankasana (bedstead), Krauncha-nishadasana (seated heron), Hastanishadasana (seated elephant), Ushtranishadasana (seated camel), Samasansthanasana (evenly balanced) and Sthira Sukhasana (any motionless posture that is pleasant).

- Pranayama

Praṇayama is made out of two Sanskrit words praṇa (प्राण, breath) and ayama (आयाम, restraining, extending, stretching).

After the desired posture is achieved, verses II.49 through II.51 recommend the next limb of yoga, praṇayama, which is the practice of consciously regulating breath (inhalation, exhalation and retention). This can be done in several ways, inhaling and then suspending exhalation for a period, exhaling and then suspending inhalation for a period, slowing the inhalation and exhalation, consciously changing the time/length of breath (deep, short breathing).

- Pratyahara

Pratyahara is a combination of two Sanskrit words prati- (the prefix प्रति-, ‘against’ or ‘contra’) and ahara (आहार, ‘food, diet or intake’). Pratyahara means not taking any input or any information from the sense organs. It is a process of retracting the sensory experience from external objects. It is a step of self-extraction and abstraction. Pratyahara is not consciously closing one’s eyes to the sensory world; it is consciously closing one’s mind processes to the sensory world. Pratyahara empowers one to stop being controlled by the external world, fetch one’s attention to seek self-knowledge, and experience the freedom innate in one’s inner world. Pratyahara marks the transition of the yoga experience from the first four limbs that perfect external forms to the last three limbs that perfect internal state, from outside to inside, from the outer sphere of the body to the inner sphere of spirit.

- Dharana

Dharana (Sanskrit: धारणा) means concentration, introspective focus, and one-pointedness of mind. The word’s root is dhṛ (धृ), which has a meaning of ‘to hold, maintain, keep.’ As the sixth limb of yoga, Dharana is holding one’s mind onto a particular inner state, subject, or topic of one’s mind. The mind is fixed on a mantra, or one’s breath/navel/tip of tongue/any place, or an object one wants to observe, or a concept/idea in one’s mind. Fixing the mind means one-pointed focus, without drifting of mind, and jumping from one topic to another.

- Dhyana

Dhyana (Sanskrit: ध्यान) means ‘contemplation, reflection’ and ‘profound, abstract meditation.’ Dhyana is contemplating, reflecting on whatever Dharana has focused on. If in the sixth limb of yoga one focuses on a personal deity, Dhyana is its contemplation. If the concentration was on one object, Dhyana is non-judgmental, non-presumptuous observation of that object. If the focus was on a concept/idea, Dhyana is contemplating that concept/idea in all its aspects, forms, and consequences. Dhyana means uninterrupted train of thought, current of cognition, flow of awareness.

Dhyana is integrally related to Dharana; one leads to the other. Dharana is a state of mind. Dhyana the process of mind. Dhyana is distinct from Dharana in that the meditator becomes actively engaged with its focus. Patanjali defines contemplation (Dhyana) as the mind process, where the mind is fixed on something, and then there is ‘a course of uniform modification of knowledge.’

Adi Shankara, in his commentary on Yoga Sutras, distinguishes Dhyana from Dharana by explaining Dhyana as the yoga state when there is only the ‘stream of continuous thought about the object, uninterrupted by other thoughts of a different kind for the same object‘; Dharana, states Shankara, is focussed on one object, but aware of its many aspects and ideas about the same object. Shankara gives the example of a yogi in a state of Dharana on the morning sun may be aware of its brilliance, color and orbit; the yogi in Dhyana state ‘contemplates on sun’s orbit alone for example, without being interrupted by its color, brilliance or other related ideas.’

- 8. Samadhi

Samadhi (Sanskrit: समाधि) means ‘putting together, joining, combining with, union, harmonious whole, trance.’ Samadhi is oneness with the subject of meditation. There is no distinction, during the eighth limb of yoga, between the actor of meditation, the act of meditation, and the subject of meditation. Samadhi is that spiritual state when one’s mind is so absorbed in whatever it is contemplating that the mind loses the sense of its own identity. The thinker, the thought process, and the thought fuse with the subject of thought. There is only oneness, samadhi.

All three (Dhyana, Dharana, and Samadhi) practised on a particular object or subject is called Samyama by Patanjali.

Sacred Practices/Sadhana

108 names of Patanjali https://www.iyengaryoga.in/s/108-Names-of-Sage-Patanjali.pdf

Patanjali Stotram https://soundcloud.com/soundsofisha/patanjali_stotram

Patanjali Stotram https://youtu.be/sWlDK86stIc

All 4 Chapters of Patanjali Yoga Sutras – Guided Chant with Narrated Meanings https://youtu.be/K6tuUaUhsyQ

Miracles

Patanjali had mastered ‘Ashtamaha Siddhis,’ the special eight spiritual powers invoked by special austerities. Many shrines have the idols of Sage Patanjali, which is believed to have metaphysical and mystical powers. It is also thought that he is benevolent and grants many boons for those who meditate on him.

Contemporary Masters

Sage Vyagrapada was his contemporary. Vyagrapada means ‘one who has a tiger’s feet.’ He belongs to the Nandinatha sampradaya sect in Shaivism and is one among the eight disciples of Maharishi Nandi who spread the teachings of Shaivism.

Holy Sites and Pilgrimages

On the 31st of October 2004, the world’s first temple dedicated to Lord Patanjali was inaugurated by Shri Yogacharya B.K.S. Iyengar in his holy birthplace of Bellur, a village in Karnataka, South India. Lord Patanjali was the son of the Divine Yogini Gonikaa and is the Divine Expounder of Yoga as taught by Lord Kapila (the primordial Holy Incarnation of Lord Vishnu, the Omnipresent Supreme Godhead). While performing Aaraadhanaa (divine worship) to the Lord, the traditional priests recite the ‘Ashtottara-shata-naamaavali’ (the 108 Names) of Lord Patanjali regularly in the holy sanctum of this temple. As explicitly mentioned in the last verse of this text, a devotee, who ardently recites these 108 names of Lord Patanjali, reaches the highest abode of consciousness by his blessings.

Chidambaram temple

In South India, there were five lingas created for the five elements in nature. Patanjali consecrated the linga for space which is in Chidambaram.

In the yogic system, the snake is used as a symbolism for unmanifest energy or kundalini because until it moves, you don’t even realise that it is there. Patanjali was such a great being; for him, divinity is not an upward movement. He is a cascade of divinity. He is the kind of human being that gods would be envious of. He is symbolically depicted in the famous half-man, half-snake form, indicating that he has risen above the duality of life and attained ultimate oneness. In doing so, he has opened the door for others to achieve the same. Half of his body has been symbolically made into a snake because he is not seen as a person anymore. He is seen as the very basis of the yogic system. His place of samadhi is said to be in Rameshwaram.

Bibliography

- “Light on Patanjali Yoga Sutras” by Yogacharya B.K.S. Iyengar.

- Babaji and the 18 Siddha Kriya Yoga tradition

External Links

https://www.iyengaryoga.in/sage-patanjali

https://www.astroved.com/astropedia/en/gods/sage-patanjali

https://isha.sadhguru.org/ca/en/wisdom/article/classical-yoga-the-influence-of-patanjali

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patanjali

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yoga_Sutras_of_Patanjali

https://www.yogiapproved.com/om/20-yoga-sutras-translated-and-explained/

https://www.gaia.com/article/patanjali-the-luminous-sage-divine-channel-of-the-yoga-sutras

https://www.himalayaninstitute.org/wisdom-library/patanjali-master-of-the-masters/

https://ecofriendlyma.com/2018/03/20/maharshi-patanjali-life-story/

https://www.chidambaramhiddentreasure.com/chidambaram-patanjali-vyaghrapada/