'Among all the globes, this earth is the only one for attaining Liberation, and among all the countries on earth, Bharatam (India) is the best. Among all the holy places (kshetras) in Bharatam where various divine powers are manifest and functioning, Arunachalam is the foremost !' 'Tiruvarur, Chidambaram and Kasi are the holy places which bestow Liberation upon those who are born in, who see, or who die in them respectively, but Arunachalam bestows Liberation upon anyone on earth who merely thinks of It!'

― ‘Sri Arunachala Venba’, verses 1 and 2

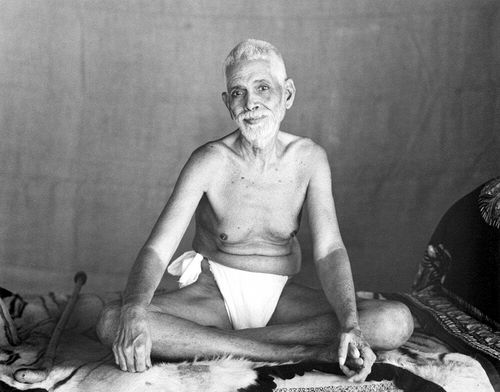

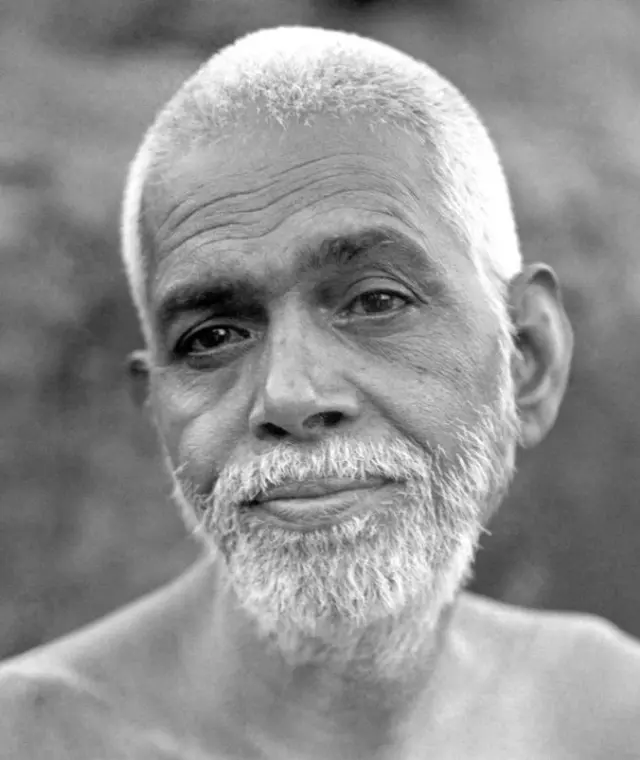

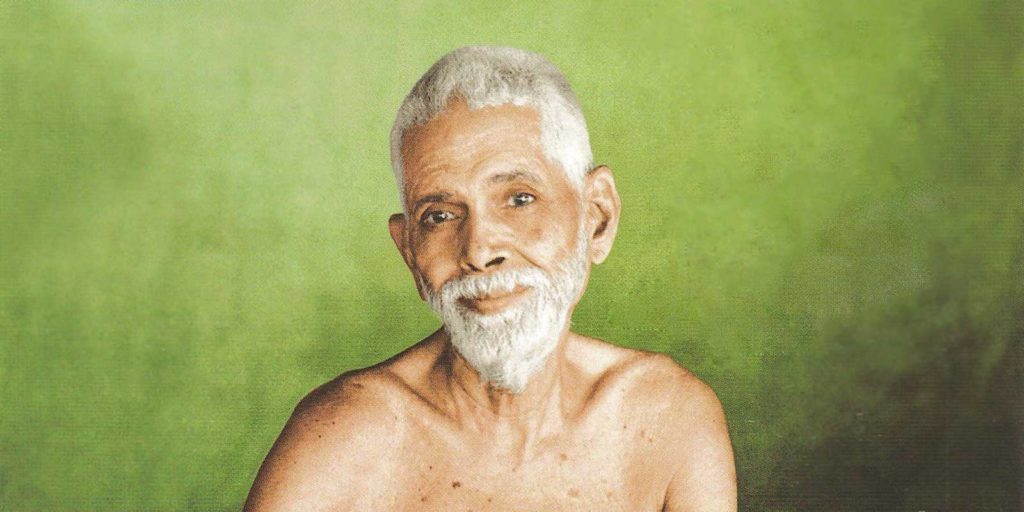

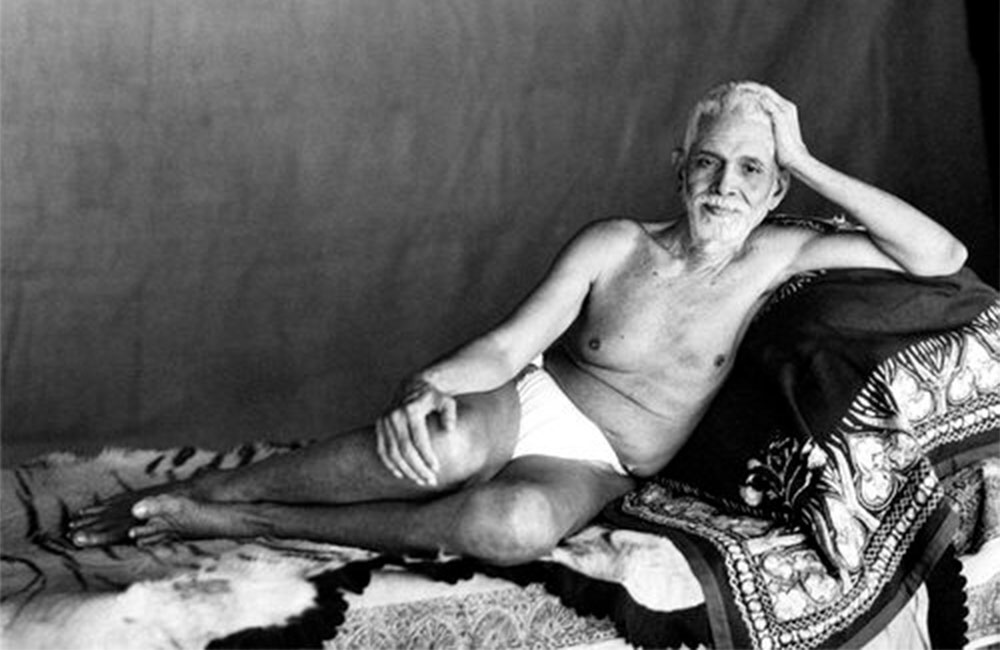

Over a hundred years ago, on September 1, 1896, Ramana, then a boy of sixteen, came all the way from Madurai to Arunachala in Tiruvannamalai, Tamil Nadu, where he lived until his death — all of fifty-four years. He considered Arunachala not just a mountain but the embodiment of Shiva, the presiding deity in the Arunachala temple. In that vision, Arunachalam is the heart of the earth, the Primal Form (Adi Lingam) of Lord Shiva. It is also the Hill of the Fire of Knowledge (jnanagni). Since it appeared as the Hill of the Light of Knowledge between Brahma and Vishnu when they were deluded, destroying their egos and teaching them true knowledge, Arunachalam was the Jnana-Guru even to them. It has held the seat (peetam) of Jnana-Guru for all three worlds from the very beginning of time. So it was a momentous meeting between the Father and Son, a meeting that marked Ramana’s transition from ‘time to timelessness.’ His abidance in the Self became unshakeable, ‘achala.’

In his ‘Aksharamanamalai,’ Ramana says: ‘Out of my house you enticed me, into the chamber of my heart you entered, and then little by little, you revealed the many mansions of your house, your infinite freedom, O Arunachala.‘

In the spiritual history of India, the advent of Ramana Maharishi at Arunachala marks a great event because Ramana is one of the most authentic saints of modern India, demonstrating that Sanatana Dharma is a living religion, not just a set of doctrines enunciated in scriptures.

So, what was the purpose of Bhagavan Arunachala Ramanan’s advent on earth? In his hymn Necklace of Nine Gems, Bhagavan reveals: ‘Arunachala [Shiva] commanded me to make known his true state of Awareness all over the world as the Self in each one’s heart, and thereby destroy the false identity that one is the body.‘ Arunachala Shiva, the infinite flame of jnana, manifested in the form of a holy hill and incarnated as Ramana to talk to us in our language. After all, who would be able to understand a hill if it were to speak? Its language is mounam, silence.

Although not explicitly, Sri Ramana made it clear that giving darshan and communicating with people through silence or brief messages of deliverance was his sole goal in life. Many seekers in various stages of spiritual evolution came to him and found peace, clarity and strength of mind in his presence. In his presence, all were alike: high or low, rich or poor, man or woman, child or adult, human or animal. He would never tolerate any consideration or attention being shown to him more than any other in the Ashram.

Among the qualities that endeared Sri Ramana to thousands was his soulabhya – easy twenty-four-hour accessibility. No permission was needed to see him, and there were no special darshan hours. In the early years, people used to sleep around him. When he had to go out at night, sometimes he had to pick his way carefully through the sleepers. He sacrificed personal privacy and sat in the hall, day in and day out.

Equally charming was his sahajata – the utter normality of behavior. His manners were so natural that the newcomer immediately felt at ease with him. By a single glance, a nod of the head, or by a simple inquiry from him, the visitor felt that Sri Ramana was his very own and that he cared for him. He was extremely humble and unassuming. There was no pontifical solemnity in his expositions; on the contrary, his speech was lively. When a devotee asked why his prayers were not answered, Sri Ramana laughingly said, ‘If they were, you might stop praying.‘

Though it was Arunachala’s command that his message is spread around the world, Bhagavan did not move an inch from Arunachala for fifty-four years. The fact is that Bhagavan did not need to move – the world came to him. Frank Humphreys was the first westerner to visit him. After that, many like Kavyakantha Ganapati Muni, Muruganar, and Arthur Osborne followed. Their only purpose was to record the message of the Master, gathering and preserving the teachings and the answers to seekers’ questions. Consequently, future generations continue to reap the benefits of his teachings.

Sri Ramana never consciously did anything to make an impact or carve out a niche for himself in the annals of history. He shunned all publicity and image building. He had successfully effaced himself.

In the 1930s, Maharshi’s teachings were brought to the west by Paul Brunton in his ‘A Search in Secret India.’ Paul Brunton lived near Sri Ramana for a few weeks in 1930, and wrote, ‘I like him greatly because he is so simple and modest, even when an atmosphere of authentic greatness lies so palpably around him; and also because he is so totally without any traces of pretension; he strongly resists every effort to canonise him during his lifetime.‘

In the 1960s, Bhagawat Singh actively started to spread Ramana Maharshi’s teachings in the US.

Ramana Maharshi has been further popularised in the west by the neo-Advaita movement, especially via the students of H. W. L. Poonja. This movement gives a western re-interpretation of his teachings by placing emphasis on insight alone. It has been criticised for this emphasis, omitting the preparatory practices. Through them, Neo-Advaita has become an prominent constituent of popular western spirituality.

Venkataraman (later Sri Ramana Maharshi) was born on December 30, 1879, at Tiruchuzhi, a small, obscure village in Tamil Nadu, some thirty miles from Madurai and eighteen miles from Virudhunagar, the nearest railway station. It was the day of Ardra Darshan. This festival celebrates that ancient, eternal moment when Lord Arunachala Shiva appeared from a primordial, infinite, fiery pillar of light to destroy the egos of warring gods and give them enlightenment. At midnight on this auspicious day, just as the idol of Shiva returned to Tiruchuzhi’s legendary Bhoominatheshwara temple, a wail of an infant was heard in a humble home on its northern street. Mother Azhagammal had just given birth to a baby boy. A baby boy who, in time, would be known the world over as Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi. Named Venkataraman as a child, the history of Bhagavan proves that the aspects of fire and light were very important throughout his life. His mother conceived many times. However, it was only when she was bearing Bhagavan that she had a burning feeling in her stomach. To soothe it, a traditional paste of neem and bilva leaves had to be applied daily on her stomach. Later, when the child was born, the blind midwife saw a brilliant light.

Venkataraman’s mother Azhagammal was a pious, devoted person; his father, Sundaram Ayyar, was a leader who practised primarily before the local magistrate. Venkataraman had a brother, two years his senior. His other brother and his sister were both younger than him by a few years. They were a happy, well-to-do middle-class family.

Endowed with a more robust constitution than most of his classmates and with a spirit of independence that marked him off from other students, Venkatraman found school games and outdoor life more agreeable than studies and reading books. Bhagavan was very well built with a powerful physique, and an excellent swimmer, football player, and wrestler. He never had a headache, stomach ache, or any ailment – so robust was his body. However, he was prone to abnormally deep sleep. Speaking about it in later years, he said: ‘The boys didn’t dare to touch me when I was awake, but if they had any grudge against me they would come when I was asleep, carry me wherever they liked, beat me, paint my face with charcoal and then put me back; I would know nothing how it happened until they told me next morning.‘

From his years of innocence, Venkataraman could hear the sound, ‘Arunachala, Arunachala,’ within himself. The sound stayed with him all the time, but he did not know what it was. Later, when he became a great Master, he was asked about it, “’f you could hear the sound all the time, why did you not ask people about it? Why did you not seek an explanation for it?’ Bhagavan replied, ‘Would someone go about checking with people if they breathe? It was built into my system, and I thought everyone could hear it too. I did not know it was an aberration.‘ Other than this, Venkataraman seemed to be an ordinary boy. Nothing spectacular about him suggested that he was to become a great Rishi.

When Venkataraman was twelve, Sundaram Ayyar died, and the family was broken up. He and his elder brother were sent to live with their paternal uncle, Subbier, who had a house in Madurai. Venkataraman first attended Scott’s Middle School and then joined the American Mission High School for his ninth grade. At school, his one asset was an amazingly retentive memory, which enabled him to repeat a lesson after hearing it just once.

In November 1895, an elderly relation spoke to Venkataraman about his visit to Arunachala, the sacred hill in Tiruvannamalai, Tamil Nadu. Since childhood, the word ‘Arunachala’ had somehow evoked inexplicable awe and love in him. So he enquired from the relative the whereabouts of Arunachala and ever afterward found himself haunted by its thoughts.

Strangely enough, he had not read any Hindu scriptures till then. He later said, ‘I did not know any terms from philosophy or spirituality – Brahman, Atman, samadhi, jnana, Self, mind – nothing.’ Then a copy of the Periapuranam fell into Venkataraman’s hands. This Purana contains stories of sixty-three Tamil Saints who could secure Lord Shiva’s grace by their exemplary devotion. As Venkataraman read the book, he was overwhelmed with ecstatic wonder that such faith, such love, and such divine fervor were at all possible. The tales of renunciation leading to Divine union filled him with awe and admiration. Something greater than all dreamlands was proclaimed real and possible in the book.

From that time onwards, the spiritual current of awareness began to wake up in the young boy. This grew ever stronger with time, and after a few months, sometime in the middle of July 1896, when he was just sixteen and a half years old, Venkataraman miraculously realised the Self. Years later, he described the event himself in the following words:

‘About six weeks before I left Madurai for good, a great change took place in my life. It was quite sudden. I was sitting alone in a room in my uncle’s house when a sudden fear of death overtook me. There was nothing in my state of health to account for it. I just felt, “I am going to die” and began thinking about it. The fear of death drove my mind inwards, and I said to myself mentally, “Now that death has come, what does it mean? What is it that is dying? Only this body dies.” And at once, I dramatised the occurrence of death. I held my breath and kept my lips tightly closed, and said to myself, “This body is dead. It will be carried to the cremation ground and reduced to ashes. But with the death of this body, am I dead? Is this body “I”? I am the spirit transcending the body. That means I am the deathless Atman.”‘

What happened next is difficult to comprehend, though easy to describe. Venkataraman seemed to fall into a profound conscious trance wherein he became merged into the very source of existence, the very essence of Being. He quite clearly perceived and imbibed the truth that the body was apart from the Atman that remained untouched by death.

Venkataraman emerged from this amazing experience as an utterly changed person. He lost interest in studies, sports, friends, and so on. His chief interest now centered in the sublime consciousness of the true Self, which he had found so unexpectedly. As a result, he enjoyed an inward serenity and a spiritual strength which never left him.

The new mode of consciousness transformed Venkataraman’s sense of values and habits. Things he esteemed earlier had now lost their appeal. In his words: ‘Another change that came over me was that I no longer had any likes or dislikes concerning food. Whatever was given to me, tasty or bland, I would swallow with total indifference.‘

After his death experience in Madurai, Bhagavan often went to the Meenakshi temple there. He would stand in front of Mother Meenakshi’s idol for hours together, looking at her eyes. Tears would flow from his eyes. Significantly, Meenakshi means ‘One with fish-like eyes.’ The Hindu scriptures describe three kinds of spiritual initiations. One of them is the way of the fish. The fish is said to have the power of hatching its eggs by just looking at them. Therefore, the inner meaning of the name Meenakshi is ‘The mother who blesses or initiates with her eyes.’ The unique gift that Mother Meenakshi gave her son Venkataraman was the power to initiate and bless his devotees with just his look. (In fact, almost every devotee of Bhagavan has talked about how the very first look from him pushed them inwards and gave them a never-before experience of joy, peace, and silence. Even on his last day, Bhagavan insisted that devotees be allowed to have his darshan – to give each one of them his final look of blessing.

Both Venkataraman’s uncle and elder brother became critical of his changed mode of life, which seemed utterly impractical. Then came the crisis on August 29, 1896. Venkataraman was then studying in tenth grade, preparing for his public examination. His teacher had given him an exercise in English grammar to be written three times. He copied it out twice and was about to do so for the third time when the futility of it struck him so forcibly that he pushed the papers away and, sitting cross-legged, abandoned himself to meditation.

His elder brother, who was watching this, scolded him for behaving like a yogi while still staying in the family and pretending to study. Such remarks had been made constantly during the last few weeks and had gone unnoticed. But this time, they hit home. ‘Yes,‘ thought Venkataraman, ‘What business do I have here?‘ Immediately came the thought of Arunachala that had caused such a thrill in him a few months ago. He then decided to discover the fabulous and legendary Arunachala of his dreams. Venkataraman knew that it was necessary to use some guile because his family would otherwise never let him go. So he told his brother that he had to attend a particular class at the school. Unintentionally providing him with funds for the journey, his brother said, ‘Take five rupees from the box and pay my college fees.’ Venkataraman took only three rupees, no more than what he thought was necessary for reaching Tiruvannamalai. In the note, he left (which fortunately is preserved), he wrote in Tamil:

‘I have set out in quest of my Father following His command. It is on a virtuous enterprise that “this” has embarked, therefore let none grieve over this act and let no money be spent in search of “this.” Your college fees have not been paid. Two rupees are enclosed.‘ The note ended with the word “Thus” and a dash — in place of his signature.

Reaching Tiruvannamalai on the early morning of September 1, 1896, after a series of trials and tribulations, Venkataraman went straight to the great Arunachaleswara temple and stood before his Father. His cup of bliss was now full to the brim. It was the journey’s end and his homecoming.

Bhagavan declared to Arunachala on the first day of his arrival at Tiruvannamalai, ‘Father, I’ve come at thy bidding. Thy will be done.‘ From that moment on, his whole life was surrendered to the Self. Coming out of the temple, the youth had his head shaven and threw away all his belongings and clothes, except for a strip he tore off his dhoti to serve as a loincloth. Thus, renouncing everything, he went back to the temple complex and immersed himself in the Bliss of Being, sitting motionless, day after day, night after night.

In the six months of his stay in the Arunachaleshwara temple, Bhagavan was continuously immersed in samadhi (deep, bodiless repose). Astonishingly, he had never heard the word samadhi or any other term to describe what he was experiencing until then. In Pathalalinga, a dark, dank, underground niche in Arunachaleshwara temple, insects and vermin feasted on his body as he sat unmindfully blissful – absorbed in the Self. Could Father Arunachala tolerate this torture to his son’s body? He sent the saint Seshadri Swami, Venkatachala Mudali, Uttandi Nayanar, and Annamalai Thambiran to give relief to Bhagavan.

Seshadri Swami brought Bhagavan’s body out from the underground cave. The others also did what they could to protect Bhagavan’s samadhi state. However, crowds of ignorant people continued to disturb Bhagavan in the temple. Consequently, Bhagavan was taken to Gurumurtam, a saint’s shrine on the outskirts of Tiruvannamalai owned by Annamalai Thambiran. Strangely, Gurumurtam too was infested with ants and other insects. Bhagavan, though, was utterly oblivious to the body. His body was unwashed, his hair had grown long, thick, and matted, and his fingernails were long and curled over. Since he hardly ate food, his body was emaciated and terribly weak. How could Arunachala bear all this? He, therefore, sent Palani Swami, his Nandi, to Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi. (On the southwest slope of Arunachala is a rock that looks startlingly like the head of Shiva’s bull, Nandi. The old devotees like Viswanatha Swami and Kunju Swami used to point it out and say, ‘That is Palani Swami – the Nandi of our Bhagavan.’)

Pilgrims and sightseers began to throng Gurumurtam, and many would prostrate themselves before the Swami, some with prayers for boons and some out of pure reverence. As the crowd became large, a bamboo fence was put around Swami’s seat to prevent the public from touching him. There was no difficulty about food, as several devotees wished to supply it regularly; the more pressing need was to keep away the crowd of sightseers and visitors.

About this time, a Malayali sadhu named Palaniswami, living in great austerity, was devoting his life to the worship of Lord Vinayaka [Ganesha]. One day a friend told him, ‘Why do you spend your life with this stone swami? There is a young swami in flesh and blood at the Gurumurtam. He is steeped in tapas like the young Dhruva. If you go there and attach yourself to him, your life will attain its purpose.’ So when Palaniswami went to the math, he was stirred to his depths at the very sight of the Swami and felt that he had discovered his saviour. So he devoted the remaining twenty-one years of his life serving the Maharshi as his attendant.

As the Swami utterly neglected his body, it got weakened to the limits of endurance. When he needed to go out, he barely had the strength to get up. Many times it so happened that he would raise himself by a few inches and then sink back again.

After Bhagavan left home, nobody knew where he was. When his mother heard the news, she was grief-stricken. She made desperate efforts to find him until one day somebody informed her that he had met a person in Tiruvannamalai who wrote his name as Venkataraman of Tiruchuzhi. Encouraged by this news, she sent her brother-in-law, a soft-hearted man, to look for her son in Tiruvannamalai. On his return, he confirmed the report, ‘Yes, I saw Venkataraman. He is totally absorbed in meditation. I pleaded with him to come back, but he did not reply. There was no response; he was just like a rock.‘

Confident that he would accept her pleas, Mother Azhagammal decided to go and beg him to return. It was 1898, two years after Bhagavan left Madurai and came to Tiruvannamalai. Bhagavan was seated on a rock at Pavazhakundru, a small hillock in Tiruvannamalai. On reaching there, his mother pleaded with him, ‘Come back home. I will not disturb you. I will feed you because you are uncared for here. I will attend to your body. I will not interfere in your life. You can continue your spiritual life there. Please come back.‘ There was no response from Bhagavan. Rock-like, he remained motionless and still. (Muruganar used to say, ‘Even a big boulder on Arunachala may move sometimes, but Bhagavan will not move. You cannot move Bhagavan.‘)

One day, some residents of Tiruvannamalai who had been seeing this old woman crying up and down the hill reproached the young ascetic, ‘Why don’t you give her a reply? Either accept or decline! We have been observing this lady cry for the last three days, and you don’t even reply!’ Relenting, Bhagavan wrote a reply on a piece of paper. This reply to his mother is his first written teaching. He wrote, ‘The Ordainer, prevailing everywhere, makes each one play his role in life according to his karma. That which is not destined will not happen despite every effort. What is destined to happen is bound to happen. This is certain. Therefore, the best course is to remain silent.‘

But it does not mean that utmost sincere efforts to succeed are not to be made. The man who says, ‘Everything is predestined; therefore I need make no effort,’ is indulging in the wrong and tricky assumption that he knows what is predestined. The mother returned home, and the Swami remained absorbed in the Self, as before.

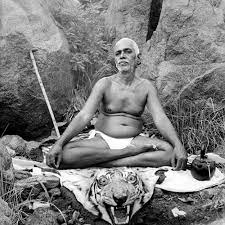

Early in 1899, the young ascetic, accompanied by his attendant Palaniswami took up his residence in the Virupaksha Cave, named after the thirteenth-century saint Virupakshadeva, whose remains lie buried there. The cave is curiously shaped to resemble the sacred monosyllable OM, the tomb being in the inner recess. He stayed in this cave for about seventeen years. Here also, the young Swami maintained silence for the first few years. His radiance had already drawn a group of devotees around him, and an ashram had come into being. He occasionally wrote out instructions and explanations for his disciples. Still, his silence did not impede their training because his most effective way of imparting instruction was through the unspoken word. Thus, the penetrating silence became the hallmark of the young sage.

Shivaprakasam Pillai, an officer in the Revenue Department and an intellectual, heard of the young Swami residing on the hill. At his first visit in 1902, he was captivated by the Swami’s aura and became his life-long devotee. As the Swami was still maintaining silence, he answered fourteen questions of Pillai by writing on a slate.

These were later expanded and arranged in a book form ‘Who am I?’; perhaps the most widely appreciated prose exposition of the Maharshi’s philosophy. Ganapati Muni, a renowned Sanskrit scholar, and poet, was another devotee who visited the Swami from 1903 onwards and accepted him as his Guru in 1907. The grateful Muni named the Swami as Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi and sang of him as an incarnation of Subrahmanya, son of Lord Shiva. Maharishi’s answers to the Muni and his disciples’ questions largely constitute the well-known work Ramana Gita.

In 1916, as the number of resident devotees increased, Sri Ramana shifted to the more commodious Skandashram, named so as it was built through Herculean efforts of his staunch devotee Kandaswami. After the death of Ramana’s mother in 1922 (who had come to stay with her ascetic son six years before and received nirvana in his hands), her body was laid to rest at the foot of the Arunachala hill. The present Ashram, named Sri Ramanasramam, has developed around the mother’s samadhi called Matrubhuteswara, God in the form of Mother. The Ashram, which began with a single thatched shed over the mother’s samadhi, has developed into a relatively large complex of buildings, the most important of which, according to many sadhakas, is the Old Hall where Sri Ramana spent most of his life for over twenty years on a couch gifted by a devotee. The shrine over Sri Ramana’s samadhi, which has a large, bright, and airy meditation hall attached to it, regularly draws many devotees and visitors throughout the year.

After Sri Ramana came down to live in the Ashram at the foot of the hill, he made it clear, though not explicitly, that giving darshan and communicating with people through silence or brief messages of deliverance was his sole goal in life. As a result, many seekers in various stages of spiritual evolution came to him and found peace, clarity, and strength of mind in his presence.

The Old Hall, currently used for meditation in Ramanasramam, was built in 1926 in which Bhagavan was given a couch, though Bhagavan himself did not like it. Bhagavan said, ‘I prefer to sleep on the rock.’ When the disciples placed a new velvet cushion on it, Bhagavan said, ‘This velvet cushion is pleasurable and enjoyable only to you. It is a bed of thorns to me. I prefer to sit on the rock.‘

Bhagavan also worked along with his devotees. All the ashram chores, including gardening, chopping vegetables, cooking, cleaning, and even masonry work, were done by Bhagavan too. He would bring rocks, mixed water, and mud for the mortar to build walls. When the Master accompanied his disciples in their work, they felt rejuvenated and happy.

A visit to Ramanasramam will show four tombs for four animals. Bhagavan treated animals just like he treated human beings; there was no difference. Just as he bestowed liberation for his mother, so he conferred mukti to a deer, a dog, a crow, and a cow – and these are just the known instances. Moreover, when Bhagavan was at Skandashram, as witnessed by Kunju Swami, as soon as a baby monkey was born, the entire group of monkeys would come to Bhagavan and place the newborn with blood and all on his lap. Bhagavan washed it and returned it to the mother. This is a remarkable phenomenon because usually if a human were to touch a newborn monkey, the whole herd would reject the infant. He also cared for the delivery of the ashram pups. Squirrels used to complain to Bhagavan, who would often mediate between them if they quarreled. He even would attend to cats whenever they were ill.

Bhagavan’s compassion for animals and birds cannot even be called extraordinary because he treated every being alike. Only because we perceive a difference between the animal kingdom and mankind, we glorify Bhagavan’s love for animals. Bhagavan was not paying any particular attention to them – he was paying equal attention to all.

The golden jubilee of Ramana’s coming to stay at Tiruvannamalai was celebrated in 1946. However, in 1947 his health began to fail. He was not yet seventy but looked much older. Towards the end of 1948, a small nodule appeared below the elbow of his left arm. Operations were performed, but the malignant tumor appeared again. The disease did not yield any treatment and was diagnosed as a case of sarcoma. The doctors suggested amputating the arm above the affected part. Ramana replied with a smile: ‘There is no need for alarm. The body is itself a disease. Let it have its natural end. Why mutilate it? A simple dressing of the affected part will do.‘ Two more operations had to be performed, but the tumor appeared again. Indigenous systems of medicine were tried, and homeopathy too. The disease did not yield itself to treatment. The Sage was quite unconcerned and was supremely indifferent to suffering. He sat as a spectator watching the disease waste the body. But his eyes shone as bright as ever, and his grace flowed towards all beings. Crowds came in large numbers. Ramana insisted that they should be allowed to have his darshan. Devotees profoundly wished that the Sage should cure his body through an exercise of supernormal powers. Ramana had compassion for those who grieved over the suffering, and he sought to comfort them by reminding them of the truth that Bhagavan was not the body: ‘They take this body for Bhagavan and attribute suffering to him. What a pity! They are sad the Bhagavan is going to leave them and go away — where can he go, and how?‘ In his unique way, he would ask whether we ever retained the leaf plate after the meal was over.

The end came on April 14, 1950. The great master gave an example of his compassion even in his last moments. Just before Bhagavan dropped the body, he asked to be assisted into padmasana. A white peacock was making sounds outside. After five minutes, Bhagavan opened his eyes and said, ‘He is hungry; feed him.‘ (In India, animals, and birds are usually referred to in the neutral gender as ‘it.’ But Bhagavan always attributed referred to them as ‘he’ or ‘she.’) These are one of the last few sentences he spoke. At 8:47, the breathing stopped. There was no struggle, no spasm, none of the signs of death. At that very moment, a bright comet moved slowly across the sky, reached the summit of hill Arunachala, and disappeared high in the sky. The super soul had returned to its source. The Jyothi of Bhagavan moved as meteor-like light and merged with Arunachala.

Sri Ramana Maharshi experienced spontaneous self-realisation at the age of sixteen when he curiously explored what it would feel like to be dead. This state later deepened during intense sadhana at Arunachala, but no Gurus or other teachers are known to have strongly influenced him.

Sri Ramana did not establish a new cult or religion. He did not insist on compliance with any existing religious mode, ritual, or line of conduct. Sri Ramana never gave discourses, much less went on lecture tours. After leaving home, he lived continuously for fifty-four years on or near the Arunachala hill. When people went to him and put questions to him, he answered them in his simple way, devoid of solemn discourses. He emphasised the unity of Being and its accessibility through one’s efforts.

When asked what the essence of his teaching was, Bhagavan would reply, ‘Either ask “Who am I?” or surrender. They are two sides of the same coin.‘ In both cases, Bhagavan said, ‘Ego has no place. When there is no ego, there is neither “I” nor “mine.” That which rules is only Arunachala.’

‘Arunachala is the Heart, the Self, the “I AM.” Reaching Arunachala is not in space or in time. It is constantly here and now. It is not going to enter your Heart. It already IS the Heart. You only have to turn your attention to it.‘

Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi has taught two principal paths for the attainment of Self-knowledge, which is the state of eternal, perfect, and unalloyed happiness. The first path he taught is the path of Self-enquiry, ‘Who am I?’, which is the path of knowledge or jnana, while the second path is the path of self-surrender, which is the path of love or bhakti.

According to him, the practical path to realisation is atma-vichara, the search for the Self, through constant and deep meditation on the question ‘Who am I?’ The approach is neither a religion nor a philosophy. It entails no belief, no scholarship, and no psychological doctrine.

Bhagavan once said, ‘The purpose of the outer Guru is to give a push; that of the inner Guru is to pull.‘ Arunachala is the outer Guru who pushes while Bhagavan remaining in the Heart as our Self, pulls us like a magnet. So what is our role? We just have to submit. Wherever we are, we should live in our Heart. Sacredness means that we should go into silence. Wherever and whenever we are in silence, we are in sacredness, which is Arunachala. Arunachala is not a Hindu god. It is reality, space, existence itself. Since we have identified ourselves with our bodies and thus have limited ourselves, Arunachala has come to remind us: ‘There is no you; there is only I AM.’

In Sri Ramana’s view, trouble and misery afflict us due to the mistake of limiting ourselves to the body. Constant self-questioning helps us understand and imbibe the true knowledge about our identity, our Higher Self (atman), residing in the body. Sri Ramana clarified that ‘Who am I?’ is not a mantra to be repeated. The purpose of asking the question is to withdraw the mind from going outward and diving deep within one’s own Self. The monkey mind, which is only a bundle of thoughts, would eventually vanish through persistent and serious meditation on the question ‘Who am I?’

Sri Ramana maintained that we are unhappy because we have failed to appreciate our true nature and the happiness inborn in the True Self. The constant urge of all of us to secure happiness in life is an unconscious search for our True Self.

Once, Bhagavan was asked, ‘What is that one thing Bhagavan, knowing which all doubts are resolved?’ Bhagavan replied, ‘Know the doubter; if the doubter be held, doubts will not arise. Recognise for certain that all are jnanis, all are realised beings. But only a few are aware of this fact. Therefore, doubts arise. Doubts must be uprooted. This means that the doubter must be uprooted. When the doubter ceases to exist, no doubts will arise. Here, the doubter means the mind.‘ Then he was asked, ‘What is the method, Bhagavan?’ Bhagavan answered sharply, ‘Enquire “Who am I?” This investigation alone will remove and uproot the doubter mind and thus establish one in the Self, the transcendental state.‘

When someone fascinated by the six chakras, the psychic centres, kundalini, and so on, asked Bhagavan about them, he replied, ‘The Self alone is to be realised. Kundalini Shakti, visions of God, occult powers, and their spellbinding displays are all in the Self. Those who speak of these and indulge in these have not realised the Self. Self is in the Heart and is the Heart itself. All other forms of manifestations are in the brain. The brain itself gets its power from the Heart. Remaining in the Heart is realising the Self. Instead of doing that, to be attracted by brain-oriented forms of disciplines and methods is a sheer waste of time. Is it not foolish to hold on to so many efforts and so many disciplines that are said to be necessary for eradicating the non-existent ignorance?‘

Sri Ramana’s teachings were mirrored to perfection in his life. He declared that to abide in the Self was the highest attainment, and it was in this transcendent state one found him at all times. He had the characteristics of a Jivanmukta – emancipated, yet in the physical body. According to the Yoga Vasistha, to such a person:

‘Pleasures do not delight; pains do not distress. He does not work to get anything for himself. There is nothing which he has to achieve. He is full of mercy and benevolence. He rests unagitated in Supreme Bliss.‘

Sri Ramana always laid stress on maunam – silence, which is not meant to be a negation of activity. On the contrary, it is something very positive. It is Supreme Peace, immutable like a rock that supports all activities, all movements.

In the evenings, Bhagavan’s attendants would beg in the streets to collect food. The traditional song they sang to collect alms was by Adi Shankara: ‘Samba Sadasiva, Samba Sadasiva, Shamba Sadasiva, Samba Sivom.‘ When the people of the town heard this refrain, they would be ready with food, knowing that Bhagavan‟s attendants were coming. Knowing this, some miscreants began to go ahead of them, sing the same song and collect the food instead. So Bhagavan’s attendants requested him, ‘Please compose a song we can sing exclusively to collect alms.’ Bhagavan, in his usual manner, kept silent.

The next day when they were going around the hill, Palani Swami called Ayya Swami, the most literate among them aside, ‘Bhagavan is murmuring something. Perhaps he is composing some verses. Take this paper and pencil.’ During that one circumambulation, Bhagavan composed one hundred and eight verses. Ayya Swami faithfully took these down. Titled ‘Aksharamanamalai’ or ‘The Marital Garland of Letters’ is one of the most spiritually moving, devotional hymns ever written.

Sri Ramana taught the Ashram inmates more by example than precept. Sri Ramana stressed that the path to peace is through service, and he set an example in the daily life at the Ashram. He would diligently correct manuscripts and proofs, cut vegetables, clean grain, shell nuts, stitch leaf-plates, and assist in cooking, thus exemplifying the dignity of labor and charm of simplicity. Karma was, for him, not some particular ritualistic action, but the daily tasks that are our familiar lot.

The most quoted shloka of the book Ramana Gita tells us: ‘In the interior of the Heart-Cave (right-hand side of the chest, not left) Brahman alone shines in the form of Atman. So, enter deep into the Heart with a questioning mind, dive deep within, or breathe under check, and abide in the Atman.‘

The earliest Western seeker to come under the Swami’s influence was F.H. Humphreys in 1911. When he asked how he could help the world, Sri Ramana replied, ‘Help yourself, and you will help the world. You are not different from the world, nor is the world different from you.‘

Fourteen Questions

Shivaprakasam Pillai posted fourteen questions to Bhagavan, who wrote the answers on a slate and in the sand. The answers were erased eventually. But Shivaprakasam Pillai wrote the answers to those questions from memory.

Sivaprakasam Pillai: ‘Swami, who am I? And how is salvation to be attained?’

M: ‘By the incessant inward inquiry, “Who am I?‟ you will know yourself and thereby attain salvation.‘

S: ‘Who am I?’

M: ‘The real “I” or Self is not the body, neither any of the five senses, nor the sense objects, nor the organs of action, nor the prana (the breath or vital force), nor the mind, nor even the deep sleep state where there is no cognisance of these.‘

S: ‘If I am none of these, what else am I?’

M: ‘After rejecting each of these and saying, “This, I am not,” that which alone remains is the “I,” and that is consciousness.‘

S: ‘What is the nature of that consciousness?’

M: ‘It is sat-chit-ananda (being-consciousness-bliss) in which there is not even the slightest trace of the “I” thought. This is also called mouna (silence) or Atma (Self). That is the only thing that is. If the trinity of world, ego, and God are considered as separate entities, they are mere illusions – like the appearance of silver in mother-of-pearl. God, ego and the world are really Shiva svarupa (the form of Shiva ) or Atma svarupa (the form of the Self).‘

S: ‘How are we to realize that reality?’

M: ‘When the seen things disappear, the true nature of the seer or subject appears.‘

S: ‘Is it not possible to realise that while still seeing external things?’

M: ‘No, because the seer and the seen are like the rope and the appearance of a serpent therein. Until you get rid of the appearance of a serpent, you cannot see that what exists is only the rope.‘

S: ‘When will external objects vanish?’

M: ‘When the mind which is the cause of all thoughts and activities vanishes, external objects will also vanish.‘

S: ‘What is the nature of the mind?’

M: ‘The mind is only thoughts. It is a form of energy. It manifests itself as the world. When the mind sinks into the Self, then the Self is realised; when the mind issues forth, the world appears, and the Self is not realised.‘

S: ‘How will the mind vanish?’

M: ‘Only through the inquiry, “Who am I?” Though this inquiry also is a mental operation, it destroys all mental operations, including itself, just as the stick with which the funeral pyre is stirred is itself reduced to ashes after the pyre and corpse have been burnt. Only then comes the realisation of the Self. The “I” thought destroyed, breath and the other signs of vitality subside.

The ego and the prana (breath or vital force) have a common source. Whatever you do, do without egoism, that is without the feeling, “I am doing this.” When a man reaches that state, even his own wife will appear to him as the Universal Mother. True bhakti (devotion) is the surrender of the ego to the Self.‘

S: ‘Are there no other ways of destroying the mind?’

M: ‘There is no other adequate method except Self Enquiry. If the mind is lulled by other means, it stays quiet for a little while and then springs up again and resumes its former activity.‘

S: ‘But, when will all the instincts and tendencies (vasanas), such as that to self-preservation, be subdued in us?’

M: ‘The more you withdraw into the Self, the more these tendencies wither and finally drop off.‘

S: ‘Is it really possible to root out all these tendencies that have been soaked into our minds through many births?’

M: ‘Never yield room in your mind for such doubts, but dive into the Self with firm resolve. If the mind is constantly directed to the Self by this inquiry, it is eventually dissolved and transformed into the Self. When you feel any doubt, do not try to elucidate it; but try to know who it is to whom the doubt occurs.‘

S: ‘How long should one go on with this enquiry?’

M: ‘As long as there is the least trace of tendencies in your mind to cause thoughts. So long as the enemies occupy a citadel they will keep on making sorties. If you kill each one as he comes out, the citadel will fall to you in the end. Similarly, each time a thought rears its head, crush it with this inquiry. To crush out all thoughts at their source is called vairagya (dispassion). So, vichara (Self Enquiry) continues to be necessary until the Self is realised. What is required is continuous and uninterrupted remembrance of the Self.‘

S: ‘Is not this world and what takes place therein, the result of God’s will? And if so, why should God will be thus?’

M: ‘God has no purpose. He is not bound by any action. The world’s activities cannot affect him. Take the analogy of the sun. The sun rises without desire, purpose, or effort, but as soon as it rises, numerous activities take place on earth: the lens placed in its rays produces fire in its focus, the lotus bud opens, water evaporates, and every living creature enters upon the activity, maintains it, and finally drops it. But, the sun is not affected by any such activity as it merely acts according to its nature, by fixed laws, without any purpose, and is only a witness. So it is with God. Or take the analogy of space or ether. Earth, water, fire, and air are all in it and have their modifications in it, yet none of these affect ether or space. It is the same with God. God has no desire or purpose in his acts of creation, maintenance, destruction, withdrawal, and salvation to which beings are subjected. As the beings reap the fruits of their actions in accordance with his laws, the responsibility is theirs, not God’s. God is not bound by any actions.‘

Later, Shivaprakasam Pillai put forth fourteen more questions. Bhagavan answered them too. These twenty-eight questions and answers make up the booklet Who am I? – an essential guide to seekers. It enables us to realise that we are the same Self, the same awareness that pervaded Sri Ramana Maharshi and still pervades all creation as the pristine truth. The essence of the fourteen other questions is below:

When Bhagavan extolled renunciation, a follower assumed that he meant sannyas. The follower went home, shaved his head, and donned a single piece of cloth. He even discarded the sacred thread that he wore all the time. Bhagavan looked at him and asked, ‘Why have you shaved your head? Go grow your hair and wear your sacred thread.‘ He then understood that Bhagavan did not want any exhibition of putting his teachings into practice. Attachment to the world or to its objects was to be relinquished from within – not displayed on the outside.

Once a childhood friend of Ramana’s asked him, ‘How many times will I be born again before I get jnana?’ Bhagavan gave a beautiful answer: ‘In reality, there are no factors like time and distance. In one hour, we dream that many days and years have passed by. In a movie, don’t you see mere shadows being transformed into vast seas, mountains, and buildings? The world is not outside you – all happens within you, like in the movie show. The small world that is in the mind appears as the big world outside.‘

Once a follower felt he could not continuously meditate or pursue Self Enquiry and stay in the Self. He confessed to Bhagavan, ‘Bhagavan, I am not able to do this. The flow gets interrupted.’ Bhagavan said, ‘Why? It is very easy. Before you go to sleep, meditate and go into the Self. Then when you fall asleep, your whole sleep will be a meditation of staying in the Self. The moment you wake up in the morning, again go into meditation for a few minutes and remain as the Self. Throughout the waking state, the undercurrent of remaining in the Self will be there even though you are working, arguing, or quarreling. This substratum will always keep you in the Self.‘ The follower thought that this was the most beautiful and practical teaching he had received from Bhagavan.

Once a follower who had experienced bliss in Bhagavan’s presence asked him, ‘Why was it that I lost the state of bliss and became unhappy again when I went back to my village? What should I do to get over my confusion and thereby gain clarity?’

Bhagavan listened to his questions with a smile and replied, ‘You have studied Kaivalya Navaneetam; one of the verses says that if one enquires into and comes to see the individual self and thus transcends it to its substratum, the eternal Self, he becomes the substratum, the Self itself. Remaining always as the Self, there will be no more births and deaths.’

Then the follower asked, ‘How can I know my Self?’

‘First, recognize who you are,’ Bhagavan answered.

‘How can I recognize who I am?’

‘See from where thoughts arise,‘ Bhagavan said.

‘But how is this to be done?’ the follower pressed.

Bhagavan replied, ‘Turn your mind inward and be the Heart. The experience of the Self as a glimpse can occur in the Guru’s presence, but it may not last. Doubts will rise again and again. The disciple should continue to study, contemplate, and practise to clear them. Studying or listening is sravana, contemplation is manana, and then practising it is nidhidyasana. Sravana, manana and nidhidyasana should be done until the distinction between the known, the knower, and the knowing no longer rises. There should be no difference, no other at all.‘

Then with his gracious look fixed on the follower, he reverted to his natural state of silence. The follower found that if any doubt arose in his mind, it was cleared by merely listening to Bhagavan’s answers to others’ questions. He rarely had to ask a question himself.

The primary practice and often repeated recommendation of Sri Ramana was vichara or self-inquiry. Continuously ask yourself, ‘Who am I, to whom do these thoughts arise?‘

T.K.Sundaresa Iyer writes:

The mantra ‘Om Namo Bhagavate Vasudevaya’ fascinated me greatly in my early days; it so delighted me that I always had a vision of Sri Krishna in my mind. I had a premonition that this body would pass away in its fortieth year, and I wanted to have a darshan of the Lord before that time. I fasted and practised devotion to Vasudeva incessantly; I read Sri Bhagavad Gita and Srimad Bhagavatam with great delight. Then when I read in the Gita ‘Jnani tu atmaiva me matam‘ (In my view, the Jnani is my own Self ), I was greatly delighted. This line of thought came to me: ‘While I have at hand Bhagavan Sri Ramana, who is Himself Vasudeva, why should I worship Vasudeva separately?’ Be it noted that all this was in my early days before settling with Bhagavan at His Ashram. So I wanted one single mantra, single worship (devata), and a single scripture, so that there might be no conflict of loyalties. Sri Ramana Paramatman easily became the God to worship; His collected works quickly became the gospel; as for the mantra, it struck me intuitively that

‘Om Namo Bhagavate Sri Ramaṇaya’

might be an exact parallel to ‘Om Namo Bhagavate Vasudevaya.’

I counted the letters in this new mantra, and was very happy to find it also contained twelve letters; I told this all to Sri Bhagavan, and He gave the mantra His approval.

Advanced practitioners (sadhaks) and thinkers may laugh at this and say: ‘Why do you need a mantra while the Ocean of Bliss is there to be immersed into directly?’ I confess that I was trying to conform to the traditional method of practice (upasana), which forms one of the main elements in bhakti (devotion). Bhagavan has revealed His true nature as the All-Witness; yet there is the explicit injunction that Advaita must be only in the attitude and never be interpreted in outer action.

Sri Ramana was much against miracles. He once said, ‘A magician deludes others by his tricks, but he himself is never deluded. A Siddha who manifests his siddhis is inferior to the magician, as he is deceiving others as much as himself.’ The ‘miracles,’ which used to happen from time to time, looked like coincidences, and if brought to Sri Ramana’s attention, he would just laugh them away. Sri Ramana would use the term ‘Automatic Divine Action’ for the ‘miracles,’ and he made the devotee believe that he had no part to play in the matter.

In 1922, Bhagavan saved Manavasi Ramaswami Iyer (Saranagati Thatha) from definite death. Kapali Shastri, an eyewitness to that miracle, has written in his book: ‘Maharshi was living on the hill in Skandashram. A few of us used to accompany him during giripradakshina (circumambulation of the mountain). On one such day before starting our giripradakshina, we got word that supervisor Ramaswami Iyer was suddenly taken ill and lying at Virupaksha cave. The Maharshi went down the hill to the place where Iyer was lying. Iyer was having violent palpitations of the heart. Maharshi sat near him, placing his hand on his head. Within five minutes, Iyer got up and looked quite normal. Maharshi kept sitting – he did not get up even after an hour. I had in my bag Skandashram olive oil, which I brought and rubbed on Maharshi’s head. Then, we all went back to Skandashram. When I asked Bhagavan, he simply replied, “Well, Ramaswami Iyer got up, and I sat down. I was conscious when the oil was rubbed; it was very pleasant.” He did not say he performed a miracle or anything like that. Later, in 1942, Iyer was once again saved from certain death. One day, his wife came running to Bhagavan and prayed that her unconscious husband in their house be saved. At that very moment, Iyer woke up. Years later, when I heard about this, I was a little skeptical. So, I went and challenged Iyer, ‘Why is it that every time you fall sick, Bhagavan saves you from death?’ He answered, “What to do, Ganesan, it is not only me who Bhagavan has saved. He also saved other sincere souls from the throes of death.” He then gave me a list – his daughter, his friend Subramani Iyer’s daughter, Jagadisa Shastri, Bhagavan‟s own sister‟s husband, and a few other names that I did not know.’

Once, Vilacheri Rangan Iyer’s (childhood friend) son was bitten by a snake, and people thought he was dead. He remembered that Bhagavan had given him sacred ash. (Probably, Rangan would have asked Bhagavan for some prasad, and Bhagavan would have obliged him with sacred ash – Bhagavan rarely gave anything as prasad of his own accord.) He told his grieving wife and relatives, ‘Do not worry, my Bhagavan, my friend, is there.’ He smeared the sacred ash on his son while chanting, ‘Ramana, Ramana, Ramana, Ramana.’ The boy recovered. Then, there was the incident when his eldest daughter became mentally imbalanced. Her husband could no longer take care of her and left her in Rangan’s care. Rangan had one solution for all his problems – Bhagavan! He wrote a letter to him and soon received a reply from the ashram saying, ‘Your letter was shown to Bhagavan, and he held it for a long time. He asked us to write back that she will be all right.‘ On another occasion, his other daughter fell into a well. When they got her out, she was thought to be dead. Everyone began to weep, except Rangan, who had faith in his friend. He had the ‘cure-all medicine’ – Bhagavan’s sacred ash. He smeared it on her, and sure enough, she recovered. Once, Rangan’s wife Chellammal went to Ramanasramam while Bhagavan was there. She could not go for circumambulation of Arunachala because of a problem with her back. Bhagavan arranged for an injection to be given by the ashram doctor, Dr. M. R. Krishnamurthy Iyer. The doctor advised Chellammal to rest in the guest house. However, she could not resist Bhagavan’s presence for even a few minutes. Finally, she managed to slowly reach Bhagavan’s hall, making her husband worried. Bhagavan just lifted his hand in blessing, and Chellammal was healed of her back pain. It never came back again. This aspect of Bhagavan was unique because he had rarely done these things for anyone else – talk about money, give sacred ash, and raise his hand to heal. He came to these realms for a true friend. What is friendship? It is a profound facet of love. And what is love? Love is wisdom, jnana, and Bhagavan was the king of jnana.

In his earlier days at Ramanasramam, Bhagavan would dry his towel on a clothesline; there was a sparrow’s nest at the end with three or four eggs. One day, while Bhagavan was pulling at the towel, one egg fell down and cracked. Bhagavan was taken aback. He told the attendant, ‘Look, look! See what I have done today!’ He took it up and, looking at it tenderly, exclaimed, ‘Oh, the poor mother will be so sorrow-stricken; perhaps even angry with me for causing the destruction of her expected little one! Can the cracked eggshell be pieced together again? Let us try!’ He then put a wet cloth around the egg and said, ‘I hope Arunachala will save me from this sin.‘ He put it back, and every few hours, he would come and change the wet cloth. After seven days, he saw that the crack had healed and said, ‘Look! What a wonder! The crack has closed, and so the mother will be happy and will hatch her egg. Arunachala has freed me from the sin of causing the loss of a life!‘ One fine morning, the egg hatched, and the little young one came out. With a gleeful face, Bhagavan took the chick in his hand, caressed it with his lips, stroked it with his soft hands, and passed it on for all to admire.

In 1938 Maharshi made a legal will bequeathing all the Ramanashram properties to his younger brother Niranjanananda and his descendants. The Ramanashram is run by Sri Niranjananda’s grandson Sri V.S. Raman. Ramanashram is legally recognised as a public religious trust whose aim is to maintain it in a way that is consistent with Sri Ramana Maharshi’s declared wishes. The ashram is to remain open as a spiritual institution so that anyone who wishes to can avail themselves of its facilities.

Writings by Ramana Maharshi are:

All these texts are in the Collected Works.

In addition to original works, Ramana Maharshi has also translated some scriptures for the benefit of devotees. He selected, rearranged and translated 42 verses from the Bhagavad Gita into Tamil and Malayalam. He has also translated a few works such as Dakshinamurti Stotra, Vivekachudamani and Dṛg-Dṛsya-Viveka attributed to Shankarachaya.

© MyDattatreya 2021 All rights reserved

Designed by Tamara Lj.