Overview and Significance

Chellappaswami, meaning ‘Wealthy Father’, was a reclusive and enigmatic Siddha who became the 160th Satguru (1840-1915) of the Nandinatha Sampradaya’s Kailasa Parampara. He lived on Sri Lanka’s Jaffna peninsula near the Nallur Kandaswami Temple in a small hut with a small samadhi shrine. Among his disciples was Sage Yogaswami, the Satguru of Satguru Sivaya Subrimuniyaswami, whom he trained intensely for five years and initiated as his successor.

Life History

Chellappaswami, Avadhuta, Siddha of Nallur

Toward the middle of the 19th century, a farmer named Vallipuram of Vaddukkoddai married Ponnamma of Nallur. They built their home near Nallur Temple and cultivated the fields. The couple had two girls and two boys, one of whom was named Chellappa. From his youth, Chellappa devoted himself one-pointedly to the pursuit of the divine within himself. He was so introverted that his parents thought him addled. Eccentric as he was, Chellappa was a pure person, strict with himself and others. He was born a yogi by all accounts—people had predicted sannyasa for him even as a youngster. He would never ask for things, even food or clothing. If he wasn’t given what he needed, he went without. He had no friends. He went to any length to hide from people, spending every free minute alone. He was close to no one. His family never knew what he was thinking, nor could they coax him out of his shell. He only withdrew all the more for their efforts.

As a young man, he had to be taken to school, or he wouldn’t go. Once there, he would sit through the day hearing and speaking nothing. It was sheer torment for everyone. His classmates mocked him, and his teachers punished him constantly for his ‘daydreaming.’ But nothing they did brought his mind down to earth. He habitually sat quietly apart from others at home, lost in his thoughts or meditating, much to his parent’s dismay. They felt that he was too serious and told him he should laugh and play like other children. He attended a Tamil primary school called Saiva Prakasa Vidyasalai at Kantharmadam, a mile from Nallur Temple.

By the time he was sixteen, Chellappa’s peculiar distance from people was so pronounced that he routinely went for days without speaking to anyone at all. His parents feared something was seriously wrong with him, and from time to time, took him to various doctors, astrologers, and other learned men, seeking a sensible diagnosis. No one could help them understand their boy. His health was sound, though he was skinny; no one knew his aloof mind. Nonetheless, he attended Jaffna Central College, a secondary school, where the medium of instruction was English. Later Chellappa took to wandering away into the countryside, to a far-off temple or village, where his family would inevitably find him, after a desperate search, meditating under a tree or aimlessly walking the roads. He patiently bore with their pleading and punishments but before long wandered off again. They learned finally to let him go. Then, finally, he would turn up, hungry and tired, after a week or two. It moved his mother to tears, and she prayed for him all her life.

A Penchant for Solitude

After leaving school, Chellappa worked as a night watchman guarding a building adjacent to a cremation ground, spending the whole night outside in the weather, making an occasional circuit of the property. He was in his late teens at the time. His parents had resigned themselves to his austere predilections, yet he managed to appall them even further. It seems that after perfunctorily checking the building he was hired to watch, he would enter the cremation yard and sit through the night meditating, often near a still-smoking pyre. Later worked at a small government office, but his penchant for solitude overcame his need for a salary.

Seeing him withdraw more and more into states they interpreted as aberrant; his relatives arranged special pujas for him in which the priests tried to exorcise the spirits they assumed had possessed him. To no avail. Chellappa was unmoved by all the fuss and unfazed by not being understood. On occasion, he even took advantage of being thought mad. It could be his ticket to do just as he pleased, to wander or be a hermit as and when he was moved to. He would mix with the sadhus of Sri Lanka, listen to their stories, and watch quietly as they debated philosophical intricacies. These were the things that engaged his mind. Understandably, the question of Chellappa’s marrying never came up, and when he met his Satguru, Kadaitswami, he was perfectly free to follow him. Released, if reluctantly, by his family and society at large, he lived as a sannyasin from his early twenties. His already intense inner life was heightened by the spiritual transformation his Guru wrought within him that his relatives hardly knew him, nor did he know them from strangers.

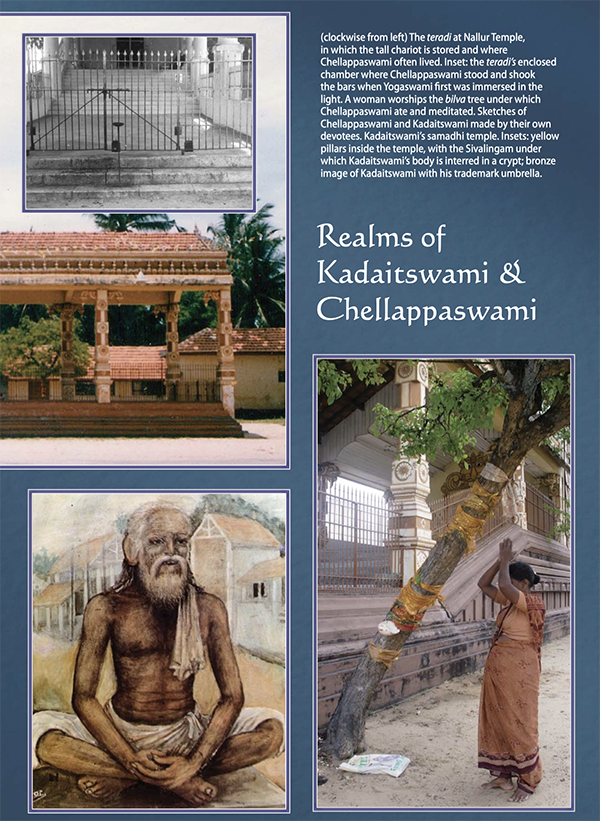

Everything about him changed and changed again. In a very short time, Kadaitswami carried him to the heights of God-Realisation, but Chellappa needed a long time adjusting to the aftermath of this profound experience. He spent long hours in deep meditation near the entrance adjacent to the Nallur Temple teradi, a large shed in which Lord Murugan’s ornate festival chariot is stored, forty-five meters from the temple entrance. In those days, it was a thatched chamber, about twelve meters tall and six meters on a side, housing the wooden parade chariot, with its two-meter-high wheels and other parade paraphernalia, which were brought out only during major festivals. In front stood a three-sided open pavilion bordered by a wrought iron fence.

Tradition and Gurus

Chellapaswami, the Avadhoot

Chellappaswami was a difficult man to be near, fiery and outspoken, bold and taunting, preferring his own company and often mumbling nonsense. With his tattered veshti and unforgiving manner, only a few strong disciples drew close to him.

Guru in the Guise of a Madman

In the weeks following his Guru Kadaitswami’s departure from the Earth plane, Chellappaswami lost all outward coherence, behaving like a madman, wild and unpredictable. He sat in the Nallur teradi portico for days and nights, motionless, hardly breathing, showing no hunger or thirst. He was an awesome figure, living in another world. Yet physically, he was awkward, with protruding teeth and thin, hay-colored hair. People brought offerings of camphor, fruit, and flowers, and sat blissfully at his feet. He spent so much time there that people referred to him as Nallur Siddhar, or Teradi Siddhar. He sat, meditated, and ate in the shade of the Bilva tree near the entry. He took up a hut with clay walls and thatched roof across the road from the teradi in the corner of his sister Chellachi’s property. For some time, she brought meals for him, but he would shout, ‘Go! Take it away! You have brought me poisoned food.’ He cooked his own meals at the hut and slept there or on the concrete steps of the teradi on a thin straw mat, living a simple life that would greatly impact others—that would, in fact, change the future of Shaivism in Sri Lanka.

When he wasn’t in samadhi, his demeanor was fierce. He threw things at anyone who approached for blessings, running and shouting after people who merely looked at him twice. People kept their distance, not comprehending this amazing being, yet sure, somehow, that he was special. This was Chellappaswami’s way—always the sage, never the saint. He often treated his disciple and eventual successor Yogaswami as if he had never seen him before, chasing him away and calling instead to some everyday passersby off the street, people who weren’t much interested in spiritual things. He would coax them sweetly to come near. Lecture, then scold them in the vilest language imaginable, telling them what scum they were—living like animals, with no thought of God or their souls, filling their bellies like pigs by day and sleeping like dogs at night, wallowing in endless desires, rushing down the royal road to hell, and so forth. He might go through every individual in the group, naming their secret vices, ticking off their private sins, abusing them right there in public. If they tried to leave, he followed them until he was through. He was unrelenting in giving forth his blessing, revealing the truth, no matter how great the humiliation.

Chellapaswami’s siddhi

His greatest siddhi was to change the life force within people, hence change their lives. These psychic powers, which he received from Kadaitswami, Chellappaswami passed on to Yogaswami. The righteous anger of these sages is to this day called ‘white anger’ by the Tamil people, the opposite of the hurtful black anger of the vitala chakra, below the muladhara chakra. Whenever in life the issue of the Guru’s fierce scoldings arose, Yogaswami challenged, ‘Is not a big fire necessary to burn rubbish?‘ Yogaswami was himself a gifted scolder in his later years, and many people were afraid to come near him. But he said that anyone who thought he was harsh should have stood for a single second before his Guru’s scolding.

Yogaswami explained that most people try to get you to love them by giving you something you like so you will pay more attention to them; you transfer some of your attachment from the thing you want to the person who gave it to you. He told disciples, ‘Chellappaguru, through subtle guile, pulled me to his side by taking everything away. He did not allow me to put on any show, nor to do any service, nor to know the future, nor to have any siddhis, nor to associate with other saints or sadhus. He did not even allow me to wonder.‘

Teachings

Jnani in the Guise of a Madman

Those were the days of British Christian domination when a Hindu sage or swami had to disguise himself to continue his inner work, when sannyasins wore white, not orange, lest they be persecuted or thrown in jail. Indeed, Chellappaswami was not mad but was likely instructed by his Guru to behave this way to avoid harassment. Nevertheless, Chellappaswami was a jnani who cloaked his greatness in unmatha avastha, the guise of a madman. Indeed, to the locals, he was known as ‘visar (mad) Chellappaswami.’ To protect him, at one point, his family had him put in chains, giving even more credence that his behavior was for real.

Chellappaswami would stagger in rapture through the streets of Jaffna, talking aloud to himself in cryptic phrases, complex and confounding, addressing everyone and no one at the same time, perhaps to discourage unworthy devotees and possibly to throw off suspicion from the British-controlled government that he might be a spiritual leader and therefore a threat to them and their evangelical efforts. It was a time in Jaffna when well over half of the traditional Shaivite families had come under the influence, temporarily as it turned out, of the conversion-hungry Catholic, Anglican, and Protestant faiths.

Years later, Yogaswami was under similar pressures and was also considered a madman by local people. But discerning villagers knew that these were the ones who were truly sane; these were the knowers of the Unknown spoken of in the Vedas. Moreover, these men were sadhus in their past lives and thus were naturally inclined to sit absorbed for hours or even days in meditation, fathoming the depths of consciousness. That the community as a whole did not comprehend this was of little concern to them.

Chellappaswami told Yogaswami that to make it known you are a Guru, a realised one, is even madder than appearing insane. Ordinary people would give you no peace. They would chase you night and day to extract blessings, almost by force, without doing anything to deserve that grace. They would come for material blessings, to have their future revealed, or just to stand near in hopes of something miraculous.

Chellappaswami continued the Parampara’s mighty mission of slowly but surely, step-by-step, awakening Shaivism within the hearts and souls of Tamils everywhere on this lush, garden island. Were it not for him; there is no way of knowing whether Shaivism would have survived into the 21st century.

Chellappaswami spoke cryptically, in a language that had to be deciphered. Here are some of his gems recorded by Yogaswami:

‘Intrinsic evil there is not‘, and ‘Absolute is Truth which none can ever comprehend‘— so saying, he would remain mute.

‘It is what it is, and there is none who can know fully, as it is concealed in dissimulation‘—so uttered the lofty Chellappan, clad in ragged clothes, and haunting Kandan’s frontal courtyard.

‘That is so from endless beginning,’ he would say and wander hither and thither.

‘It’s all illusive phenomena‘, he muttered, ‘Who knows?‘

‘It was all settled long ago‘ and went about the outer courtyards of Nallur Temple and sat in the dirt, saying that all that dirt would frighten away the people who came to fall at his feet.

Yogaswami shared: ‘I don’t think anyone ever got from him a straight answer to a question. I merely stood and waited behind him for the occasional gem that fell out of all the mad talk.‘

Sacred Practices/Sadhana

The Nallur Temple was the centre of life for Chellappaswami. With a shakti vel enshrined within its innermost sanctum, this ancient Murugan temple is even today the most prominent Hindu temple of the Jaffna peninsula; some say because of the presence of the lineage.

Miracles

Kadaitswami visited Chellappaswami there often, and together they went on long walks and meditated at out-of-the-way places. One afternoon, on a particularly scorching day, while Chellappaswami was sitting in the shade in the Nallur compound, he suddenly put up his umbrella and held it there as if he were in the sun. Ten minutes later, Kadaitswami arrived, and Chellappaswami put the umbrella down. Witnesses surmised that Chellappaswami had felt his Guru coming and put up his umbrella to mystically shelter him from the hot sun as he walked.

Chellappaswami’s nephew, his sister’s son, lived in her house. Even though he acknowledged Chellappaswami was a Sage, the young man was hot-tempered. He often lost his temper with the swami because Chellappaswami used such harsh and filthy language toward him, his mother, and other family members, sometimes offending their friends and visitors. One day, Chellappaswami was standing by the open water well in the family compound, scolding his sister in a loud, angry voice. Running out of the house to defend his mother, the youth began screaming at Chellappaswami to stop. Chellappaswami yelled back at him, mocking his words. Suddenly the boy jumped across the two-meter-wide well to get at the swami, both fists flying as he landed on the other side. Chellappaswami touched him lightly on the chest, and immediately all his anger was stilled. It vanished entirely. The boy just stood there, dumbfounded, blinking in shock, not knowing where he was.

The family learned through the years to respect Chellappaswami’s advice. Once, they and a few close friends planned a pilgrimage to Kataragama, the most famous of Sri Lanka’s Skanda temples, located in the tiger-infested jungles deep in the southern hills. They saved their money and talked about the journey for months ahead of time. Chellappaswami knew they were going. When the day finally came to depart, though, he said, ‘Why go searching? God is here.‘ They unpacked immediately, all but one of the party, who set out by himself. As it turned out, he never reached Kataragama. He fell desperately ill with malaria along the way and returned to Jaffna only after six months in the hospital and thousands of rupees in doctor’s fees.

Chellappaswami expected to be left alone. Even his own devotees approached only on invitation, visiting less on their initiative than his. If they needed anything from him, they would already have received it. He knew their minds. Devotees often sought his help at crucial times in their life.

A child of Ramalingam of Columbuthurai was seriously ill. The parents were eager to take the child to Swami, but his mother-in-law warned them, ‘We do not know to what caste that madman belongs. So do not take the child to him.’ Brushing off this older woman’s words, Ramalingam and his wife took the child to Swami. When he saw them, Swami ordered, ‘Kanakamma, bring the child here!‘ Then, giving instructions to take the child to a native physician for a particular medicine, he declared, ‘Your mother is speaking of caste. I swear by the Sun and the Moon that we are no other than Vellala caste from Vaddukkottai.‘ When Swami touched the child, the temperature went down, and upon receiving the prescribed medicine, the child was entirely cured.

If strangers drew near, stopping out of curiosity to see what he was doing, he would scold, throw things and chase them away. He would throw anything—dirt, mud, rocks, cow dung, garbage—so that they would let him be. Chellappaswami corrected devotees’ misdeeds in every scolding and touched the sorest and most sour area of their inner mind. They trusted him to know just where they were imperfect, just where they needed to change for spiritual progress. They hated these upbraidings because they revealed those things that they most wanted to hide and because they were delivered with a spiritual force so penetrating that it felt like a deep psychic surgery. Yet, again and again, they went back for more, receiving those incisive corrections as divine blessings. They invariably improved in the days and months after his fiery grace descended on them in all its terrible fury. Just being in his presence, receiving a modicum of that infinite shaktipat, transformed them, made them different, somehow better.

Contemporary Masters

The Nandinatha Sampradaya to which Chellappaswami belonged continued uninterruptedly after his passing with Yogaswami, who became the Guru of Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, founder of the Himalayan Monastery on Kauai. Before his death, he appointed Bodhinatha Veylanswami as his successor. Satguru Bodhinatha Veylanswami is the current head of the Monastery.

Holy Sites and Pilgrimages

Nallur

Theradi Chellappah Swami (1840-1915) was a Jnani who greatly enhanced the sacred power of the Nallur. As he spent most of the time reposing on the steps of theradi where the Nallur temple chariot is kept, he was known as Theradi Chellappar. Chellappah’s parents from Vattukodai, settled in Nallur to cultivate their lush, fertile fields. Chellappah was educated at Jaffna Central College and later joined Jaffna Kachcheri as an Arachi. Very soon, ascetic inclination overwhelmed his mind. Though outwardly he carried on his regular work, inwardly he was soaring high spiritually. During this phase, he was also blessed by Kadaitswami, who frequented the Nallur Temple precincts. When the midnight puja was over and all had left, he would hurry to the entrance of the Kandaswami temple. Intoxicated with divine fervor in mystic communion, he would call out to Lord Murugan of Nallur ‘Appa! Appa!’

Chellappa Swami, the Avadhuta, appeared outwardly like a madman, like one possessed by Spirits, like an innocent child. To the masses, he was a madman Visar Chellappa. To confirm himself in the guise of a madman, he behaved more and more erratically. Many supernatural powers siddhis manifested in him, but he openly declared, ‘Chellappah will not exhibit any such powers; he will be known as a madman to the world and quit away.’ However, the earnest seekers, his devotees identified him as a great spiritualist; they felt sad seeing his radiant face crowned with uncombed hay-like hair and his thin, wiry body wrapped in filthy rags.

For more information about the Nandinatha Sampradaya and Kailasa Parampara visit:

Kauai Hindu Monastery, 107 Kaholalele Road, Kapaa, Hawaii, 96746-9304,

- USA E-mail: [email protected]

Bibliography

Sources:

- The Guru Chronicles, the Making of the First American Satguru – Swamis of Kauai’s Hindu Monastery

- Dancing with Shiva, Hinduism’s Contemporary Catechism – Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami