Overview and Significance

YOGASWAMI – ‘MASTER OF YOGA’

Yogaswami, Sri Lanka’s most renowned contemporary spiritual master (1872‒1964), is a Sivajñâni and Nâtha Siddhar revered by both Hindus and Buddhists. He was trained in and practiced kundalini yoga under Satguru Chellappaswami, from whom he received guru diksha. He was 161st Jagadacharya of the Nandinatha Sampradaya‘s Kailasa Parampara. Sage Yogaswami was, in turn, the Sat Guru of Sivaya Subramuniyaswami (1927-2001), 162nd Sat Guru of the Nandinatha Sampradaya’s Kailasa Parampara. Yogaswami conveyed his teachings in hundreds of songs, called Natchintanai, ‘Good Thoughts’, urging seekers to follow dharma and realize God within. Sage Yogaswami, the protector of dharma, was Satguru of Sri Lanka for half a century.

Four great sayings encapsulate his message:

[1] Thanai ari, ‘Know thy Self by thyself;’

[2] Sarvam Sivam Ceyal, ‘Siva is doing it all;’

[3] Sarvam Íivamaya, ‘All is Siva;’ and

[4] Summa Iru, ‘Be still.’

Life History

Courtesy: Hinduism Today

‘At 3:30am on a Wednesday, in May of 1872, a son was born to Ambalavanar and Sinnachi Amma not far from the Kandaswamy temple in Maviddapuram, Eelam (Sri Lanka). He was named Sadasivan. Because his mother died before he reached age ten, he was raised by his aunt and uncle. He was bright but independent in his school days, often studying alone high in the mango trees. After finishing school, he joined government service as a storekeeper in the irrigation department and served for years in the verdant backwoods of Kilinochchi.

The decisive point of his life came when he found his guru outside Nallur Temple in 1905. As he walked along the road, Sage Chellappan, a disheveled sadhu, shook the bars from within the chariot shed where he camped and shouted at the passing brahmachari, ‘Hey! Who are you?’ That simple, piercing inquiry transfixed Sadasivan. ‘There is not one wrong thing!’ ‘It is as it is! Who knows?’ the jnani roared, and suddenly everything vanished in a sea of light. The world was renounced in that instant.

At a later encounter amid a festival crowd, Chellappa ordered him, ‘Go within; meditate; stay here until I return.’ He came back three days later to find Yogaswami still waiting for his master.

Yogaswami surrendered himself completely to his guru, and life for him became an intense spiritual discipline, severe austerity, and stern trials. One such trial, ordered by Chellappa, was a continuous meditation that Chellappa demanded of Sadasivan and Kathiravelu in 1909. For 40 days and nights, the two disciples sat upon a large flat rock. Chellappa came each day and gave them only tea or water. On the morning of the fortieth day, the guru brought some string hoppers. Instead of feeding the hungry yogis, he threw the food high in the air, proclaiming, ‘That’s all I have for you. Two elephants cannot be tied to one post.’ It was his way of saying two powerful men cannot reign in one place. Following this ordination, their sannyasa diksha, he sent the initiates away and never received them again.

Chellappa passed away in 1911. Yogaswami, obeying his guru’s last orders, sat on the roots of a huge olive tree at Colombuthurai. Under this tree he stayed, exposed to the roughest weather, unmindful of the hardship, and serene as ever. This was his home for the next few years. Intent on his meditative regime, he would chase away curious onlookers and worshipful devotees with stones and harsh words.

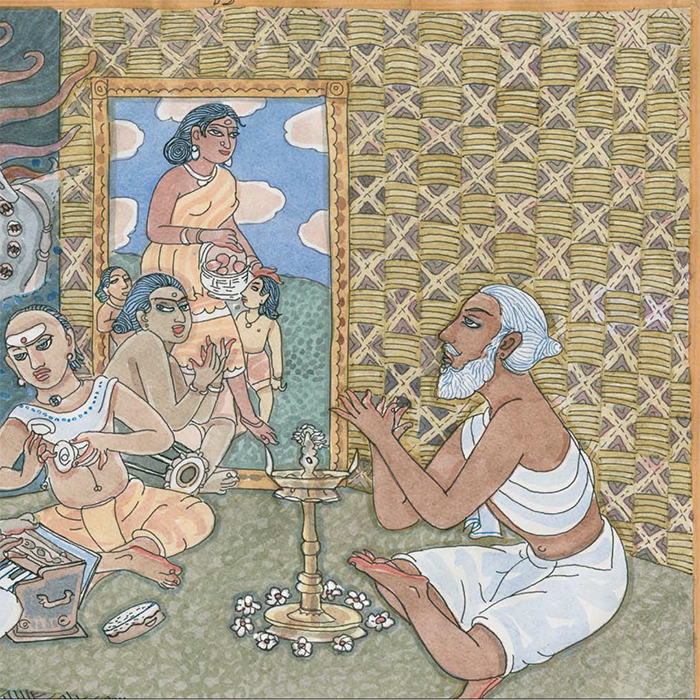

After years of austere meditation under an Illupai (olive) tree, he was persuaded to inhabit a small hut in Colombuthurai made by loving devotees. Here it was his habit to wake up early and, in the dark before dawn, light camphor in worship of the holy sandals, the thiruvadi, of his guru. Once the sun rose, he would stride through the countryside, walking many miles each day. Few recognized his attainment.

But this changed significantly one day when he traveled by train from Colombo to Jaffna. An esteemed and scholarly pandit riding in another car repeatedly stated that he sensed a ‘great jyoti’ (a light) on the train. When he saw Siva Yogaswami disembark, he cried, ‘You see! There he is.’ The pandit canceled his discourses, located and rushed to Siva Yogaswami’s ashram, prostrating at his feet. His visit to the hut became the clarion call that here indeed was a worshipful being.

From then on, people of all ages and all walks of life, irrespective of creed, caste, or race, visited Yogaswami. They sought solace and spiritual guidance, and none went away empty-handed. He influenced their lives profoundly. Decades passed, and he came to be Illathusiddhar, the Perfected one of sea-girt Illangai. Later, people of all walks of life, all nations, and paths came for his darshan. Many realized how blessed they were only after years had passed. Yogaswami’s infinite compassion never ceased to impress. He would regularly walk long miles to visit Chellachchi Ammaiyar, a saintly woman immersed in meditation and tapas. Yogaswami would feed her and attend to duties as she sat in samadhi. Upon her directive, her devotees, some of the most learned elite of Sri Lanka, transferred their devotion to Satguru Yogaswami after her passing.

He would mysteriously enter the homes of devotees just when they needed him, when ill or at the time of their death. He would stand over them, apply holy ash and safeguard their passage. He was also known to have remarkable healing powers and comprehensive knowledge of the medicinal uses of herbs. Countless stories tell how he healed from afar. He would prepare remedies for ill devotees. Cures always came as he prescribed. When not out visiting devotees, Yogaswami would receive them in his hut. From dawn to dusk, they came and listened, rapt in devotion.

In 1940, Yogaswami went to India on pilgrimage to Banaras and Chidambaram. His famous letter from Banaras states, ‘After wanderings far in an earnest quest, I came to Kasi and saw the Lord of the Universe — within myself. The herb that you seek is under your feet.’

One day he visited Sri Ramana Maharshi at his Arunachalam Ashram. The two simply sat all afternoon, facing each other in eloquent silence. Not a word was spoken. Back in Jaffna, he explained, ‘We said all that needed to be said.’

As the years progressed, Swami enjoyed traversing the Jaffna peninsula by car, and it became a common sight to see him escorted through the villages. Followers became more numerous, so he gave them all work to do, seva to God and the community. In December 1934, he had them begin his monthly journal, Sivathondan, meaning both ‘servant of Siva’ and ‘service to Siva.’

On February 22, 1961, Swami went outside to give his cow, Valli, his banana leaf after eating, as he always did. Valli was a gentle cow. But this day, she rushed her master, struck his leg, and knocked him down. The hip was broken, not a trivial matter for an 89-year-old in those days. Swami spent months in the hospital and, once released, was confined to a wheelchair.

Devotees were heart-stricken by the accident, yet he remained unshaken. He ever affirmed, ‘Siva’s will prevails within and without — abide in His will.’ Swami was now confined to his ashram, and devotees flocked to him in even greater numbers, for he could no longer escape on long walks. He was, he quipped, ‘captured.’ With infinite patience and love, he meted out his wisdom, guidance, and grace throughout his final few years.

At 3:30 am on a Wednesday in March of 1964, Yogaswami passed quietly from this earth at age 91. The nation stopped when the radio spread the news of his great departure, and devotees thronged to Jaffna to bid him farewell. Though enlightened souls are often interred, it was his wish to be cremated. Today, a temple complex has been erected on the site of the hut from which he ruled Lanka for 50 years.

He was one of those rare souls, like the rishis of yore, living in the infinity of Truth within all things, which he called Siva. His very name came to mean wisdom, mystery, spiritual power, and knowledge of the timeless, formless, spaceless Self within, Parasiva. He was revered equally by Hindus, Buddhists, and Muslims. Devotees continue to honour him with pada puja, worship of the master’s feet, which contain the fullness of enlightenment and hold the promise of our own spiritual freedom.

Yogaswami articulated his teachings in hundreds of poems and songs, called Natchintanai or Mahavakyam.

YOGASWAMI’S FIRST MEETING WITH CHELLAPPASWAMI

Yogaswami was about twelve at the time. Suffering from an infected cut on his foot, he was on his way to the doctor’s hut in Jaffna town. As he passed by the teradi at Nallur Temple, a man shouted, ‘Come here! What do you want with medicine?’ It was Chellappaswami, who beckoned him closer and had him sit down while he examined the wound, nodding his head like a doctor. Chellappaswami told him not to go to the ayurvedic doctor but to mash a particular herb and apply it as a poultice to the wound. The foot healed in a few days. That was the only time Yoganathan had been near the sage as a child, though he undoubtedly saw him from time to time around Nallur Temple through the years.

Amid a festival crowd outside Nallur temple, a disheveled sâdhu shook the bars from within the chariot shed, shouting, ‘Hey! Who are you?’, and at that moment, Yogaswami was transfixed. ‘There is not one wrong thing!’ ‘It is as it is! Who knows?’, Sage Chellappan shouted, and suddenly the world vanished.

After Chellappan’s mahâsamâdhi in 1915, Yogaswami undertook five years of intense sâdhana. Later, people of all walks of life, all nations, came for his darshan. He urged one and all to ‘Know thy Self by thyself.’

Tradition and Gurus

THE ROLE OF THE GURU

‘Though himself unattached, the guru, after testing him for some time, on command of the Lord, shall deliver the Truth to his disciple to vest him with authority. Of him who is so invested with authority, there is certainly union with the Supreme Íiva. At the termination of the bodily life, his is the eternal liberation—this is declared by the Lord. Therefore, one should seek with all effort to have a guru of the unbroken tradition, born of Supreme Íiva himself. It is laid down by the Lord that there can be no moksha, liberation, without dîkshâ, initiation; and initiation cannot be there without a teacher. Hence, it comes down the line of teachers, paramparâ. Without a teacher, all philosophy, traditional knowledge, and mantras are fruitless. Him alone the Gods laud who is the guru, keeping active what is handed down by tradition.’

— Kulâr∫ava Tantra 10.1. kt, 101

YOGANATHAN RECEIVES HIS FIRST TEACHING FROM CHELLAPPASWAMI

Yoganathan’s friends had visited Chellappaswami many times, and Yoganathan could not help but be keenly aware of the majestic being, but now he was standing face to face with the great one. After a few moments, Chellappaswami dismissed the three householders, shouting, ‘Go and look after your families! You fellows are not fit to become sadhus.’ Yoganathan, on the other hand, was kindly invited to stay back: ‘I was awaiting your arrival here. I am going to have a coronation for you soon.’ Drawing Yoganathan to his side, he gave him instruction in spiritual values, then suddenly slapped him on the head with his right hand, exclaiming, ‘This is the coronation!’, and then he voiced five momentous teachings

~ Summa iru. (Be still).

~ Eppavo mudintha kaariyam. (It was all finished long ago).

~ Naam ariyom. (We know not).

~ Muluthum unmai. (All is truth).

~ Oru pollupumillai. (There is not one wrong thing).

Yogaswami later wrote: ‘Then and there I received divine grace.’ Once these words were imprinted in the heart of the devotee, then Chellappah, his face blossoming with grace, said, ‘It is good, dear one; come, I have been waiting for a person like you.’ That evening at sunset, still overwhelmed by the encounter, Yoganathan walked back alone to his aunt’s house. Those who recalled those times said that following this experience, the young man often met with Chellappaswami on weekend trips from Kilinochchi.

Moment of Truth

A subsequent meeting, which Yogaswami described years later in his Natchintanai, was equally transformative. Yoganathan was walking along the road outside Nallur Temple. Sage Chellappaswami shook the bars from within the chariot shed where he camped and boldly challenged, ‘Hey! Who are you?” (‘Yaaradaa nee?’).

Yoganathan was transfixed by the simple, piercing inquiry. Their eyes met, and Yoganathan froze. Chellappaswami’s glance went right to his soul. The sage’s eyes were like diamonds, fiery and sharp, and they held his with such intensity that Yoganathan felt his breathing stop, his stomach in a knot, his heart pounding in his ears. He stared back at Chellappaswami. Once he blinked in the glaring sun, and a brilliant inner light burst behind his eyes.

‘He revealed to me Reality is without beginning or end; he enclosed me in the subtlety of the state of summa. All sorrow disappeared; all happiness disappeared! Light! Light! Light!’

Waves of bliss swept his limbs from head to toe, riveting his attention within. He had never known such beauty or power. For what seemed ages, it thundered and shook him while he stood motionless, lost to the world. He later described it as a trance.

‘To end my endless turning on the wheel of wretched birth, he took me beneath his rule, and I was drowned in bliss. Leaving charity and tapas, charya and kriya, by fourfold means he made me as himself.’

The roaring of the nada nadi shakti—the mystic, high-pitched inner sound of the Eternal—in his head drowned out all else. The temple bells faded in the circling distance as from every side, an ocean of light rushed in, billowing and rolling down upon his head. He couldn’t hold on, not for an instant. He let go, and Divinity absorbed him. It was him, and he was not.

Yoganathan stood transfixed, like a statue, for several minutes. As he regained ordinary consciousness and opened his eyes, Chellappaswami was waiting, glaring at him fiercely. ‘Give up desire!’, he shouted. People were passing to and fro, unaware of what was taking place. ‘Do not even desire to have no desire!’

Yoganathan felt the grace of the guru pour over and through him, all from those piercing eyes. Such ecstasy he had never known. Dazed, he saw that the guru intended to dispel all darkness and delusion with his words, which were beyond comprehension at that moment: ‘There is no intrinsic evil. There is not one wrong thing!’

Yogaswami later wrote of this dramatic meeting in a song called ‘I Saw My Guru at Nallur’:

‘I saw my guru at Nallur, where great tapasvins dwell. Many unutterable words he uttered, but I stood unaffected. ‘Hey! Who are you?’, he challenged me. That very day itself his grace I came to win.’ I entered within the splendor of his grace. There I saw darkness all-surrounding. I could not comprehend the meaning. ‘There is not one wrong thing,’ he said. I heard him and stood bewildered, not fathoming the secret. As I stood in perplexity, he looked at me with kindness, and the Maya that was tormenting me left me and disappeared. He pointed above my head and spoke in Skanda’s forecourt. I lost all consciousness of my body and stood there in amazement. While I remained in wonderment, he courteously expounded the essence of Vedanta, that my fear might disappear. ‘It is as it is. Who knows? Grasp well the meaning of these words,’ he said and looked me keenly in the face—that peerless one, who such great tapas had achieved! In this world, all my relations vanished. My brothers and my parents disappeared. And by the grace of my guru, who has no one to compare with him, I remained with no one to compare with me.’

As Yoganathan tried to comprehend the experience, his guru had already forgotten him there. Chellappaswami was scanning distant rooftops, mumbling to himself and nodding in accord with all he was saying, then began walking away. Yoganathan started to follow when the sage called back over his shoulder, ‘Wait here ’till I return!’ It was three full days before his guru came back, and the determined Yoganathan was still standing right where he left him. Chellappaswami didn’t speak or even stop. He motioned for Yoganathan to follow, leading him to the open fire pit where the sadhu prepared his meals. There he served Yoganathan tea and a curried vegetable stew, then sent him away. He didn’t welcome or praise his new disciple; he didn’t say to come back or not to come back. He didn’t have to. Yoganathan knew he had been accepted. And his training began—the first chance he got, he bent to touch Chellappaswami’s feet, and his guru bellowed in dismay. Drawing back, the sage scolded him, ‘Don’t even think of it!’ Yoganathan was bewildered, but he obeyed, and his guru calmed down. ‘You and I are one,’ he said. ‘If you see me as separate from you, you will get into trouble.’

Teachings

Since most of his followers were Hindus, his teaching was expressed mainly in Hindu terms, but he was beyond all distinctions of religion. Buddhists, Christians, Muslims, and agnostics would all come to him for help and guidance, for he had reached the summit to which philosophies and religions are merely paths. Like a good doctor, he knew what was best for each of his ‘patients’ and altered his ‘prescriptions’ accordingly. His teaching embraced all the yogas and, at the same time, lay beyond all of them.

Nearly all of his devotees were householders and engaged in some employment or other, and apart from one or two exceptions, he rarely advised them to retire from their employment. People would often come and say that they wanted to give up their jobs to devote more time to spiritual practices. Still, he did not usually encourage them to do this since, for him, the whole of man’s life had to be made a spiritual practice. He would not admit any division of human activity into holy and unholy.

Yogaswami had a set of favourite aphorisms that he loved to repeat when devotees or strangers called on him. It was from his guru Chellappa that Yogaswami had first learned these lines. These are called the Great Sayings (Mahavakyas). It is generally accepted that these four spiritual truths, which are often quoted nowadays, contain the essence of Yogaswami’s teachings:

~ Oru pollappum illai : There is no evil at all; nothing is wrong. ‘Good’ and ‘evil’ are man-made distinctions. From the standpoint of the Absolute, there is neither good nor bad. What we call ‘evil’ is part of the Leela or play of the Lord. One cannot understand His ways or decisions. What one considers to be wrong or objectionable may have a Divine purpose and may even be a blessing in disguise.

~ Muzhudum unmai: All is Truth (the whole thing is true). The sage who is fully realized sees the entire universe as a manifestation of God. He is not separate from the universe, for He is Himself the universe. What we see as the created universe, the manifest and the unmanifest, are, in fact, extensions of the Creator Himself. So the jivanmukta sees God in every tree, in every grain of sand, in every living creature, and every inanimate object. God is not separate from what He created.

~ Nām Ariyom: We do not know. We know nothing. We are incapable of knowing the Unborn, the Uncreated, and the Unconditioned with our narrow conditioned minds. Our minds are limited instruments that can only comprehend things of a mundane nature. But the mind cannot know God. Besides, we are incapable of understanding the ways of God.

~ Eppavo Mudintha Karyam: The event was completed long ago. It was all over long ago. Everything has been pre-ordained. A man may like to think that he can determine the course of his life and, in a general sense, even shape the course of human affairs. It feeds the vanity of man to think that he can shape the future. But man is a mere instrument in the hands of God. It is God alone who controls the past, present, and future. Ego-centered man prides in the belief that he has free will when in actuality, he is a mere puppet in the hands of an unseen power. One had better accept this fact and surrender oneself to God.

NATCHINTANAI, “GOOD THOUGHTS’

Yogaswami conveyed his teachings in over 3,000 poems and songs, called Natchintanai, ‘good thoughts’, urging seekers to follow dharma and realize God within. These gems flowed spontaneously from him. Any devotee present would write them down, and he occasionally scribed them himself. Natchintanai has been published in several books and through the primary outlet and archive of his teachings, the Sivathondan, a monthly journal he established in 1934. To this day, Yogaswami’s devotees intone Natchintanai songs during their daily worship. Natchintanai is a profound tool for teaching Hinduism’s core truths.

Some quotes from the Natchintanai:

~ As a dog, let loose after being tied up for some time, is energetic and active, so one who learns to remain summa, or still, gets increased energy which can be put to good use.

~ If the chimney is full of smoke, how can the light be seen? If the mind is full of dirt, how can the soul shine?

~ You are your own friend; you are your own enemy.

~ There is one thing God cannot do. He cannot separate Himself from the soul.

~ All great ones have undergone suffering. None can escape what is ordained.

~ Just as a man will use a staff to climb a mountain, so should virtue be used in life.

~ Meditate, soul is Siva.

~ Say I am He, and meditate daily; all the mental attachments (aasai) will disappear, and the Grace of Siva will be showered.

~ Oh the mind, Worship as one (with me) the Being that shines as this world, soul, and higher Reality.

~ Believe in God —- Think that I am not —- God is existing — Whoever thinks of something, he becomes that — Ultimately all will be seen as He.

~ I have the greatness to meditate as I am He. In whatever way one meditates, he becomes in that way.

~You are not the mind, not budthi, not chitham. You are Atma. Atma never perishes.— Practice as the soul is in the presence of God — God exists inside and outside.

~ Siva, in His inherent form, is inseparable from Shakti.

A VISITOR DESCRIBES HIS MEETING

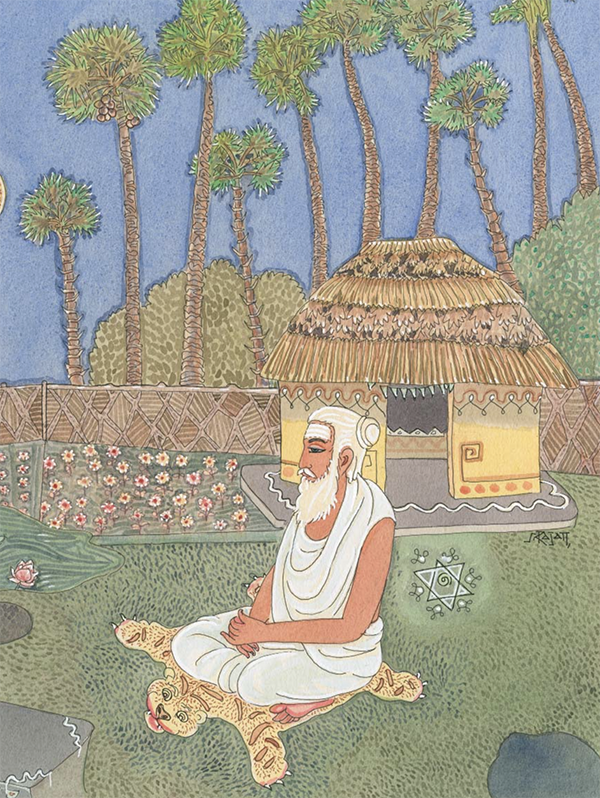

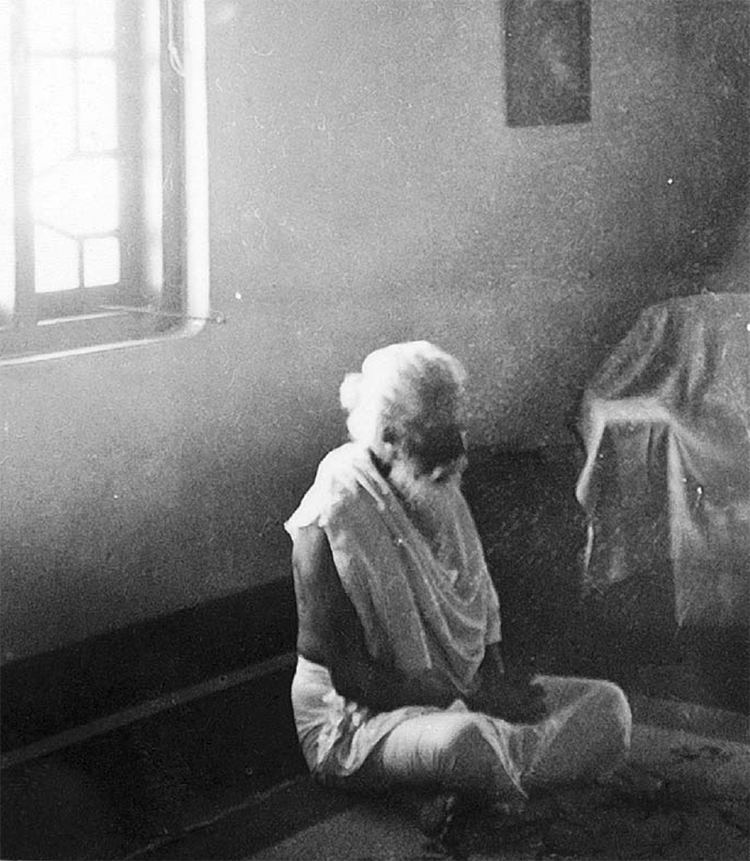

‘It was a cool and peaceful morning except for the rattling noises owing to the gentle breeze that swayed the tall and graceful palmyra trees. We walked silently through the narrow and dusty roads. The city was still asleep. Yogaswami lived in a tiny hut that had been specially constructed for him in the garden of a home in the city of Jaffna. The hut had a thatched roof and was on the whole characterized by the simplicity of a peasant dwelling. Yogaswami appeared exactly as I had imagined him to be. He looked very old and frail. He was of medium height, and his long grey hair fell over his shoulders. When we first saw Yogaswami, he was sweeping the garden with a long broom. He slowly walked towards us and opened the gates.

‘I am doing a coolie’s job,’ he said. ‘Why have you come to see a coolie?’ He chuckled with a mischievous twinkle in his eyes. I noticed that he spoke good English with an impeccable accent. As there is usually an esoteric meaning to all his statements, I interpreted his words to mean this: “I am a spiritual cleanser of human beings. Why, do you want to be cleansed?”

He gently beckoned us into his hut. Yogaswami sat cross-legged on a slightly elevated platform, and we sat on the floor facing him. We had not yet spoken a single word.

That morning we hardly spoke, for he did all the talking. Talking to him was unnecessary, for one only thought of something, and he replied instantaneously. I did not have to formulate my questions into words, for Yogaswami was aware of my thoughts all the time.

After we had comfortably sat on the floor, Yogaswami closed his eyes and remained motionless for nearly half an hour. He seemed to live in another dimension of his being during that time. One wondered whether the serenity of his facial expression was attributable to the joy of his inner meditation. Was he sleeping or resting? Was he trying to probe into our minds? My friend indicated with a nervous smile that we were fortunate to have been received by him. Yogaswami suddenly opened his eyes. Those luminous eyes brightened the darkness of the entire hut. His eyes were as mellow as they were luminous – the mellowness of compassion.

I was beginning to feel hungry and tired, and thereupon, Yogaswami asked, ‘What will you have for breakfast?’ I would have accepted anything that was offered, but I thought of idly (steamed rice cakes) and bananas which were popular food items in Jaffna. In a flash, there appeared a stranger in the hut who respectfully bowed and offered us these items of food from a tray that he was holding. My friend wished for coffee a little later, but before he could express his request in words, the same man reappeared on the scene and served us with coffee.

After breakfast, Yogaswami asked us not to throw away the banana skins for the cow. He spoke loudly to the cow that was grazing in the garden. The cow clumsily walked right into the hut. He fed her with the banana skins. She licked his hand gratefully and tried to sit on the floor. Yogaswami held out the last remaining banana skin to the cow and said, ‘Now leave us alone. Don’t disturb us, Valli. I have some visitors.’ The cow nodded her head in obeisance and faithfully carried out his instructions.

After the cow had left us, Yogaswami closed his eyes again, and he seemed once more to be lost in a world of his own. I was indeed curious to know what exactly Yogaswami did on these occasions by closing his eyes. I wondered whether he was meditating. It was a wrong moment to broach the subject, but he suddenly started speaking before I could ask any questions.

‘Look at those trees. The trees are meditating. Meditation is silence. If you realize that you know nothing, then you would be truly meditating. Such truthfulness is the right soil for silence. Silence is meditation.’

Yogaswami bent forward eagerly. ‘You must be simple. You must be utterly naked in your consciousness. When you have reduced yourself to nothing – when your ‘self’ has disappeared – when you have become nothing, you are yourself God. The man who is nothing knows God, for God is nothing. Nothing is everything. Because I am nothing, you see, because I am a beggar – I own everything. So nothing means everything. Understand?’

‘Tell us about this state of nothingness,’ requested my friend with eager anticipation.

‘It means that you genuinely desire nothing. It means that you can honestly say that you know nothing. It also means that you are not interested in doing anything about this state of nothingness.’

What, I speculated, did he mean by ‘know nothing’ – the state of ‘pure being’ in contrast to ‘becoming’?

‘You think you know, but in fact, you are ignorant. When you see that you know nothing about yourself, then you are yourself God.’

Yogaswami frequently alluded to this state of silence. He spoke of it as though it was his very life. Any description of it will necessarily remain an abstraction to one who has not experienced this state of samadhi. In his presence, one caught a fleeting glimpse of that bliss. Whether Yogaswami’s consciousness expanded to include those in his immediate presence, or whether this feeling of indescribable joy or peaceful bliss or samadhi was based on self-deception, is a matter that cannot be easily decided. Almost everything that Yogaswami said seemed so amazingly simple that one could not help but become temporarily oblivious to his statements’ practical implications. Then, for a moment, as though to assert the independence of my mind, I tried to scrutinize his sayings in my mind without asking any questions.

Is this state an act of divine grace? Is it possible to induce this state in oneself? Does one come by this state accidentally without any exertion of will? Would not any attempt to induce silence inevitably activate the ego? Yogaswami, who was aware of these doubts and difficulties, came to my assistance with an unforgettable pithy remark: ‘There is silence when you realize that there is nothing to gain and nothing to lose.’

Our conversation that was taking an interesting turn was interrupted by a man who walked into the hut. This person was an ardent devotee of Yogaswami. He lit a candle, placed a few jasmine flowers on the floor, and finally prostrated himself on the cold cement floor before kissing Yogaswami’s feet.

‘Bloody fool!’, yelled Yogaswami, ‘This is not an altar! Are you worshipping me, or are you worshipping yourself? Why worship another?’ The poor man withdrew into a corner of the hut with reverence and trembling.

‘Do you think,’ went on Yogaswami, ‘that you can find God by worshipping another? You do such silly, stupid things – offering flowers and lighting candles! Do you think that you can find God by giving bribes?’

In situations of this kind, Yogaswami’s strictures did not appear to originate from his pedagogic role of a guru or spiritual teacher as many of his disciples would probably have supposed. Still, they were instead the casual and incidental remarks of someone who was deeply moved by human folly. Indeed, Yogaswami discouraged recording his sayings, which he likened to rubbish that did not deserve preservation. He regarded that the veracity of a spontaneously uttered statement depended on the unique and unrepeatable circumstances that gave rise to it.

Yogaswami waved his hands with disapproval at that man who had just worshipped him. He then pressed his quivering hands against his heart in an eloquent gesture and exclaimed loudly, ‘Look! It is here! God is here! It is here!’

For a few moments, he closed his eyes again. These interludes were probably intended to allow the meaning of his pronouncements to sink gradually into the minds of his listeners. There was a strange, majestic, and Buddha-like dignity whenever Yogaswami closed his eyes in meditation – the erect spine and the cross-legged posture together with the face that was asleep but yet supremely awake.

‘The time is short, but the subject is vast,’ he whispered with extreme gravity. This enigmatic statement may mean that the subject of understanding God or reality is vast. In contrast, the time at one’s disposal is so limited that it should not be wasted in non-essentials such as rituals and ceremonies.’

Sacred Practices/Sadhana

Yogaswami spent years of intense tapas under the olive tree at Colombuthurai Road on the outskirts of Jaffna. His practice was to meditate for three days and nights in the open without moving about or taking shelter from the weather. On the fourth day, he would walk long distances, returning to the olive tree to repeat the cycle. In his outward behaviour, Yogaswami followed the example of his guru, for he would drive away those who tried to approach him. After some years, he allowed a few sincere seekers to approach him. As more and more devotees gathered around him, his austere demeanor relaxed. He was eventually persuaded to occupy a small hut in the garden of a house near his olive tree. This remained his ‘base’ for the rest of his life. Even here, he initially forbade devotees to revere or care for him. Devotees would come to him for help with all their problems, usually in the early mornings and evenings. Day and night, Yogaswami was absorbed in his inner worship. On one occasion, Yogaswami was seated in perfect stillness, like a stone. A crow flew down and rested several minutes on his head, apparently thinking this was a statue.

Meditation on Siva

The gurus of the Kailasa Parampara emphasize that to realize God, we must go beyond the intellect’s limitations and concepts. To guide seekers on the path to this experience, Yogaswami stressed the importance of meditation and formulated a key teaching or mahavakya: ‘Tannai ari’, ‘Know thyself’. This was a second dominant theme of his teachings. He proclaimed, ‘You must know the Self by the self. Concentration of the mind is required for this…. You lack nothing. The only thing you lack is that you do not know who you are.… You must know yourself by yourself. There is nothing else to be known.’

Markanduswami, a close devotee of Yogaswami, would later tell visitors to his hut: Yogaswami didn’t give us a hundred-odd works to do. Only one: realize the Self yourself, know thy Self, or find out who you are. What, exactly, does it mean to know thy Self? Yogaswami explained beautifully in one of his published letters: ‘You are not the body; you are not the mind, nor the intellect, nor the will. You are the Atma. The Atma is eternal. This is the conclusion at which great souls have arrived from their experience. Let this truth become well impressed on your mind.’

Knowing that most people are trepidatious about meditating deeply, diving into their deepest Self, Yogaswami gave assurance that inner and outer life are compatible. He counseled, ‘Leave your relations downstairs, your will, your intellect, your senses. Leave the fellows and go upstairs by yourself and find out who you are. Then you can go downstairs and be with the fellows.’

Miracles

Even when Yogaswami was alive, he had a considerable reputation in Sri Lanka and India as a truly enlightened sage. His devotees naturally tended to exaggerate his spiritual accomplishments. He had been hailed as the greatest seer the world had known since Shankara. Some skeptics dismissed him as just another yogi with psychic powers. Even those who questioned whether he had been fundamentally transformed in the spiritual sense did nevertheless readily concede that he had extraordinary psychic powers.

Yogaswami was reputed to have been remarkably clairvoyant. He was known to disappear from one place in space and reappear at several places simultaneously. Three of his devotees claimed to have met him at the same moment in time in places as far distant as Jaffna (Sri Lanka), Madras, and London. One of his close friends recalled incidents that illustrated that anything wished by Yogaswami immediately materialized. For instance, this person had accompanied Yogaswami on a long walk in the country across many miles of rice fields. Yogaswami, having experienced the pangs of hunger and fatigue, had casually wished for a car to ride back to town. No sooner had he uttered this wish than there were several cars on the scene. The drivers of the cars were all requesting Yogaswami to step into their vehicles. The drivers were vying for the privilege of being of some assistance to the holy man. On this occasion, Yogaswami had raised his hands and exclaimed how dangerous it was to wish! Spiritually liberated persons, I was told, were incapable of wishing in the psychological sense as their egos had dissolved, but their wishes were confined to purely physical needs.

On another occasion, at the end of one of Yogaswami’s rare visits to Colombo, a large crowd of admirers had thronged a railway station in Colombo to see his departure. Some devotees were chanting hymns in Sanskrit and Tamil, while a few others were offering him garlands of flowers. It was getting late, and one of Yogaswami’s friends had alerted him to the importance of catching his train in time. ‘Don’t worry,’ replied Yogaswami assuredly, ‘the train cannot leave without me.’ That evening there had been engine trouble, and the train failed to start at the right time. After leisurely greeting all his friends, Yogaswami finally decided to enter his railway compartment, and the train thereupon started to move.

Contemporary Masters

Yogaswami revered and was deeply motivated by other Hindu leaders of his time. In 1889, Swami Vivekananda was received in Jaffna by a large crowd and taken in festive procession along Columbuthurai Road. As he neared the illuppai tree where Yogaswami later performed his tapas, Vivekananda stopped the procession and disembarked from his carriage. He explained that this was sacred ground, and he preferred to walk past rather than ride. He described the area around the tree as an ‘oasis in the desert.’ The next day, the 18-year-old Yogaswami attended Vivekananda’s public speech. He later recalled that Vivekananda paced powerfully across the stage and ‘roared like a lion’—making a deep impression on the young yogi. Vivekananda began his address with, ‘The time is short, but the subject is vast.’ This statement went deep into Yogaswami’s psyche. He repeated it like a mantra to himself and spoke it to devotees throughout his life.

'Don’t go halfway to meet difficulties. Face them as they come to you; God is always with you, and that is the greatest news I have for you.'

― Vivekananda

On one occasion, Yogaswami divulged his respect for Mahatma Gandhi. He related, ‘Two European ladies came to see me. They had been in India to see Mahatma Gandhi and wanted a message from me. I asked them what Gandhi had told them. The Mahatma had said, ‘One God, one world.’ I told them I could not think of a better message and sent them away.’ Yogaswami also met the great sage Ramana Maharshi on a pilgrimage to India.

Holy Sites and Pilgrimages

For more information about the Nandinatha Sampraday and Kailasa Parampara, visit:

Kauai Hindu Monastery, 107 Kaholalele Road, Kapaa, Hawaii, 96746-9304

USA E-mail: bodhi@hindu.org

Bibliography

Sources:

- The Guru Chronicles, the Making of the First American Satguru – Swamis of Kauai’s Hindu Monastery

- Dancing with Shiva, Hinduism’s Contemporary Catechism – Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami

- Yogaswami, The Life and Teachings of Sri Lanka’s Great Master (1872-1964) – Editors of Hinduism Today